Today is a slow day. It’s the Feast of St. Barnabas, with whom Protestants ought to be familiar as an important figure of the New Testament Church and faithful companion of the Apostle Paul. There is a much more vivid tradition about Barnabas in the Eastern Orthodox Church than here in the West, of which …

Tag Archives: saints

What is a Saint? An Introduction for Protestants

It occurred to me the other morning in the shower (that’s where thoughts usually occur to me) that many Protestants might be troubled by the concept of saints and sainthood. I have heard Protestants say, “We don’t believe in saints.” I assure you that you do. Do you believe that there are people in Heaven? …

Continue reading “What is a Saint? An Introduction for Protestants”

St. Ignatius of Antioch on the Episcopacy

St. Ignatius, Bishop of Antioch, is one of our most vivid testimonies to the Early Church at the beginning of the second century. Arrested by the Roman Empire and sentenced to die, ca. A.D. 108, Ignatius wrote a series of letters to various churches while en route to his martyrdom in the arena at Rome. …

Continue reading “St. Ignatius of Antioch on the Episcopacy”

St. Boniface, Apostle of the Germans

Today is the Feast of St. Boniface (c. 7th century – 754), known as the Apostle of the Germans. Born with the name Wynfrith in the English kindgom of Wessex, he was renamed Boniface by Pope Gregory II, who commissioned him. He spent the last thirty years of his life as a missionary to the …

Why Protestants Should Care

So, I finally revealed my blog to my Facebook and Twitter friends. And a good many of them have followed me. Being a little more public has brought about a good bit of self-scrutiny: Am I relevant? Why should anybody want to read my blog? Why should Protestants, in particular, want to read my blog? …

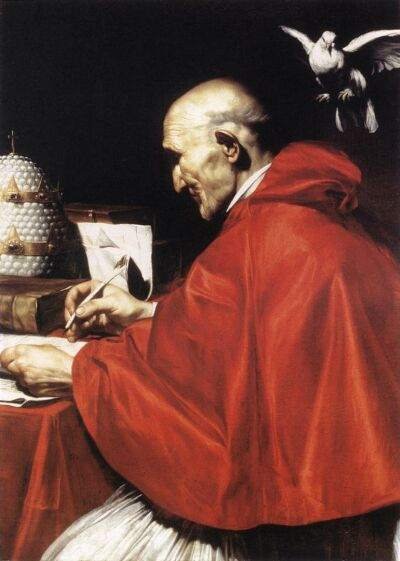

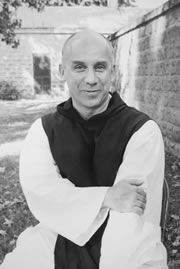

Thomas Merton on Saints

“It is a wonderful experience to discover a new saint. For God is greatly magnified and marvelous in each one of His saints: differently in each one. There are no two saints alike: but all of them are like God, like Him in a different and special way. In fact, if Adam had never fallen, …

St. Justin Martyr on Christian Baptism

St. Justin Martyr (100–165) was a second-century Christian apologist and one of our earliest testimonies to the worship of the Early Church. A pagan convert, he died a Christian martyr in Rome. In St. Justin’s First Apology (ca. 150), he writes regarding Christian Baptism: I will also relate the manner in which we dedicated ourselves …

Early Testimonies to St. Peter’s Ministry in Rome

So I’m realizing why the “tomb of st. peter” is such a popular search term. It seems the issue of St. Peter’s presence and ministry in Rome is one of the major points of contention between Catholics and many Protestants (especially those of an anti-Catholic bent). This is somewhat surprising to me. Even as a …

Continue reading “Early Testimonies to St. Peter’s Ministry in Rome”

The Bones of St. Peter

This should be the conclusion of my three-parter on the Tomb of St. Peter at St. Peter’s Basilica on the Vatican, in which I hope to discuss the discovery of St. Peter’s relics and the issue of their authenticity. Also, a bibliography! Previously, “The Tomb of St. Peter,” “The Grave of St. Peter.“ The bones …

The Grave of St. Peter

Last time, I gave a brief history of the tomb of St. Peter on the Vatican, and of the excavations in the 1940s that uncovered the ancient pagan necropolis beneath St. Peter’s Basilica. I left the matter of the excavation of the tomb itself for this post — which is bound to be a little …