A little something I whipped up last week for somebody — in rejection of the idea that the saints are “dead,” that praying to the saints is “communication with the dead,” and that this is an “occult” practice (one of the more bizarre anti-Catholic claims I have heard). My interlocutor was not receptive, but I thought this might be helpful to someone else.

Man is Appointed Once to Die, Then Comes Judgment

You seem to be advocating a form of the doctrine of “soul sleep” or mortalism, the belief that the soul becomes dormant between earthly death and the Final Judgment, an error the Christian Church has condemned consistently since the earliest times. Scripture reveals to us that the dead in Christ receive a particular judgment at the moment of their deaths, rather than “dying” until the Final Judgment. Hebrews 10:27–28 tells us that “it is appointed once for men to die, and then comes judgment” and that at the end of the age, “Christ will appear a second time … to save those who are eagerly awaiting Him”; that will be the Final Judgment, for which both the just and the unjust will be resurrected in body and judged (Acts 24:15, John 5:28–29, Matthew 25:31, 32, 46). Scripture shows us in more than a few places that the dead have immediate destinations, rather than entering a “holding place.” Jesus’s parable of the rich man and Lazarus (Luke 16:22) presents the living and conscious souls of both men in their respective dispositions, not dead or dormant or asleep. Jesus promised the good thief on the cross that he would be with Him in Paradise that very day (Luke 23:43).

The Four Doctors of the Western Church: Pope St. Gregory the Great, St. Ambrose, St. Augustine, and St. Jerome.

The Spirits of Just Men Made Perfect

We have every reason from Scripture to believe that there awaits a heavenly reward for righteous men and women who die in Christ. St. Paul presents that apart from his body, he might be at home with the Lord (2 Corinthians 5:6–8) — not dormant or dead until a later judgment. Given the choice between life and death, his desire was to depart and be with Christ — for to live is Christ and to die is gain — but chose to remain and serve the people of God (Philippians 1:21–24). Hebrews 12:23 presents “the assembly of the first-born who are enrolled in heaven, and … the spirits of just men made perfect” — a very clear indication of the eternal life already received by worthy Christians who have passed on.

The Communion of Saints

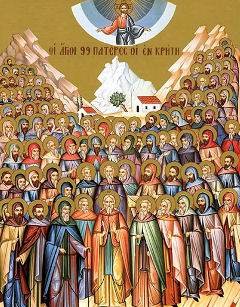

And when these souls have passed from their earthly walk, what is their relation to the living Church? We know that in Baptism we all are joined to the Body of Christ (1 Corinthians 12:12–13, Galatians 3:27), and that in the Body of Christ we share an organic unity with all other believers (Romans 12:4–5, 1 Corinthians 10:17, 12:12–20, Ephesians 4:4). We know that in Christ we have eternal life, and we know that Christ, being raised from the dead, will never die again (Romans 6:9). Therefore we have no reason to believe that bodily death has cut those who have passed from this life off from Christ or off from us. Rather than dead or dormant, our dear departed are more alive now than they’ve ever been. As we have communion with Christ, we have communion with each other, with all other believers — all who are in Christ from all ages. Since the earliest times, the Church of Christ has affirmed this communion of saints, as declared in the ancient creeds.

Communicating with the Dead?

So, the idea than in praying to and with the saints — as they pray with and for us — we are “communicating with the dead,” is erroneous. The practice condemned by Isaiah (Isaiah 8:19) and the Torah (Leviticus 19:31, 20:6, 27, Deuteronomy 18:11) is explicitly the communication with the dead through “mediums and wizards” — “consulting the dead on behalf of the living” for the sake of personal gain or advantage or divine or supernatural knowledge, expecting a supernatural dialogue from beyond the grave, as Saul sought to do with the spirit of the prophet Samuel through the witch of Endor (1 Samuel 28). The “occult” — the etymology of which refers to “closed” or “hidden” or “dark” knowledge — includes specifically sorcery, witchcraft, wizardry, astrology, spiritism, and necromancy — which is not simply “communicating with the dead,” but communicating with the dead through these dark arts, by contacting spirits through rituals or spells or séances. Prayer — in and with and through the Holy Spirit — in no way resembles any of this. We pray in the light, in the open, with voices lifted to God, not through hidden or dark or arcane wisdom.

To “pray,” in the most literal sense, means to ask, to petition, to plead, to beseech — and this is all it means to “pray” to the saints: to ask for the intercession of our Christian brothers and sisters who are in and with Christ in heaven, as we also intercede for all our brothers and sisters in Christ, as St. Paul urges us to “make intercession for all men” (1 Timothy 2:1–5). Paul himself continued to intercede for his departed friend (2 Timothy 1:16–18) — showing that he did not consider those who had fallen asleep in Christ to be beyond his reach or help.

Virgin Mary (c. 1600), by El Greco. (WikiPaintings.org)

The Prayers of the Saints

And Scripture again reveals to us the reality of this heavenly intercession. The Revelation of John presents the twenty-four elders — widely interpreted as the Patriarchs and Apostles — offering up golden bowls of incense to God, “which are the prayers of the saints” (Revelation 5:8) — “saints” in this context referring to both the living and the dead in Christ (cf. Revelation 11:18, 16:6, 24) — demonstrating plainly that the prayers of Christians living on earth are heard by the holy souls in heaven, and that heavenly intercessors are involved in presenting these prayers to God. We likewise see the angels in heaven similarly offering up our prayers (Revelation 8:3). Thus, we see that though Jesus Christ is the one Mediator between man and God (1 Timothy 2:5) — that it is only by Jesus that we can reach the Father (John 14:6) — this by no means abrogates our call to intercede for one another, or of others to intercede for us — least of all those who have passed to their glorious reward.