(This is a matter I’ve written about before, but not all in one place. And it’s come up in a conversation, so I thought I would put it all together here.)

Anti-Catholics often claim that there is no evidence in Scripture that the Apostle Peter died in Rome or even ever went there. After all, wasn’t Peter the Apostle to the Jews, and Paul the Apostle to the Gentiles? What would Peter have been doing in Rome? Nevermind that early first century Rome had a Jewish population of over 7,000, perhaps many more; or that Peter was the first to preach to Gentiles, just as Paul ministered to Jews everywhere he went. And as a matter of fact, there is strong biblical evidence to place Peter in Rome by the close of the events of the New Testament.

She who is at Babylon

First, and most clearly: Peter tells us himself. In the closing of St. Peter’s first epistle, he writes:

By Silvanus, a faithful brother as I regard him, I have written briefly to you, exhorting and declaring that this is the true grace of God; stand fast in it. She who is at Babylon, who is likewise chosen, sends you greetings; and so does my son Mark. Greet one another with the kiss of love. Peace to all of you that are in Christ (1 Peter 5:12–14)

She who is at Babylon, who is likewise chosen, sends you greetings. Who is Peter talking about? Who is she? And how can someone who is in Babylon be sending greetings through Peter? Does that mean Peter is in Babylon? Let’s take this apart.

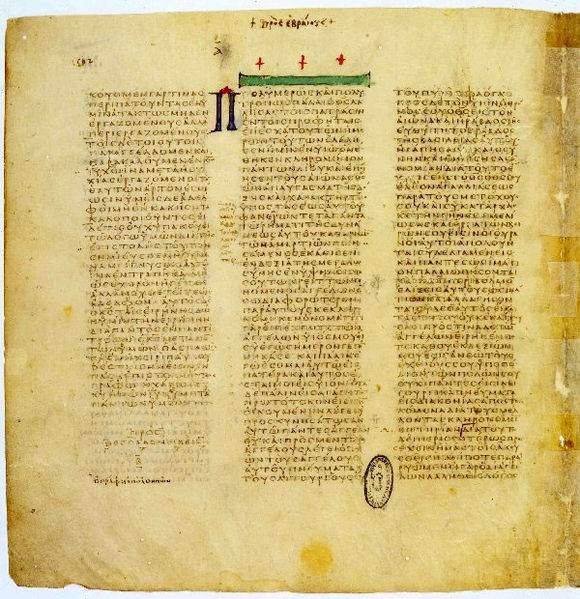

First of all, the Greek here — as well as an astute reading of the English — gives us a strong hint who she is. “She who is in Babylon, who is likewise chosen” is ἡ ἐν Βαβυλῶνι συνεκλεκτὴ [hē en Babylōni syneklektē]. What does he mean, likewise chosen? Who else is chosen? For the answer, we return to the opening of the letter:

Peter, an apostle of Jesus Christ, to those chosen sojourning of the Diaspora in Pontus, Galatia, Cappadocia, Asia, and Bithynia, according to the foreknowledge of God the Father, by the sanctification of the Spirit, for obedience and sprinkling with the blood of Jesus Christ: Grace to you and peace, may it be multiplied. (1 Peter 1:1–2, my translation)

I gave my own translation, more literal than any published one (so literal as to sound a little awkward, probably), to preserve the order and emphasis of Peter’s words: Peter’s address is to those chosen. The Greek word here is ἐκλεκτόι [eklektoi] — and this mirrors the word from 5:13, συνεκλεκτόι [syneklektoi = syn + eklektoi], also chosen. This word, ἐκλεκτός [eklektos], from ἐκ + λέγω [ek + legō] — it most literally means to choose out. It is the root of our English words elect and eclectic.

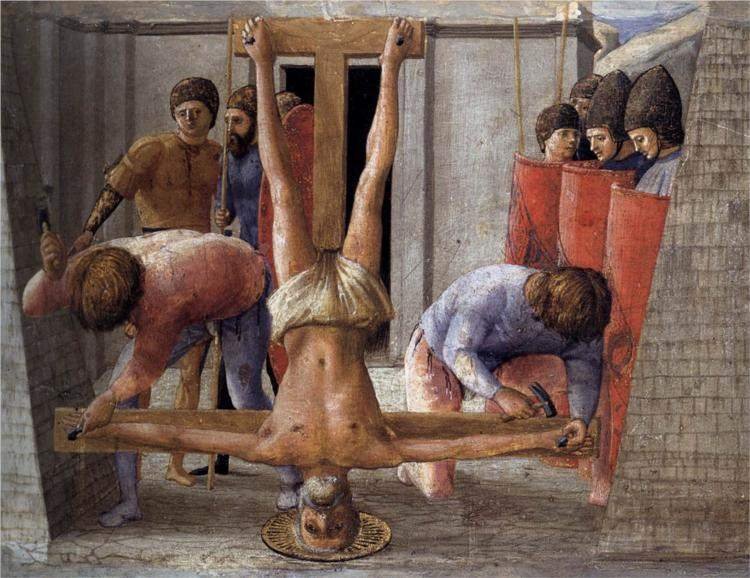

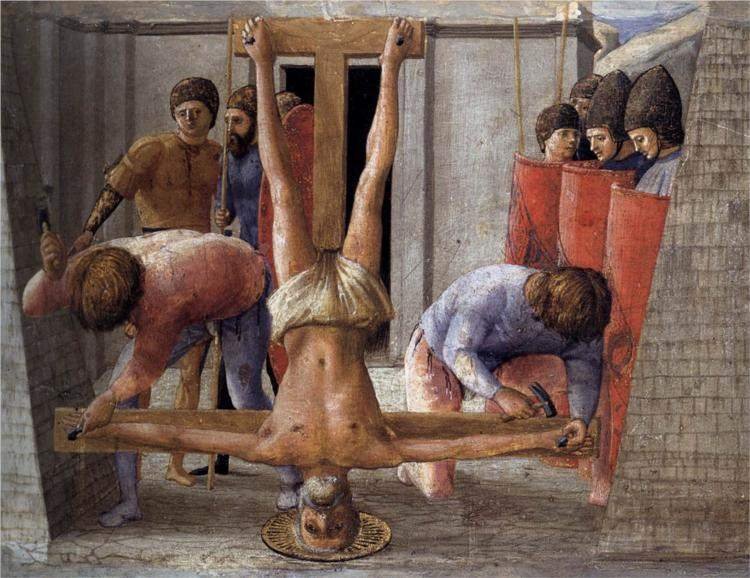

The Crucufixion of St. Peter (1426), by Masaccio (WikiPaintings).

We have here what is called an inclusio, a literary envelope by which the opening and closing of the letter bracket the contents. Peter wants to emphasize the fact of being chosen. The people to whom Peter is writing are those chosen by God, and she who is at Babylon is also chosen or elect. Elsewhere in the New Testament the “elect” refers to all Christians (cf. Luke 18:7, Romans 8:33, 2 Timothy 2:10). And in another place, we find a reference to an unnamed “elect lady”: John the Presbyter writes “to the elect lady and her children” (2 John 1) — and sends greetings from “the children of your elect sister” (2 John 13). Who are these elect ladies, if not the Church, sisters in different places?

But the elect lady at Babylon? If Peter is by her side, then he must be in Babylon, too, must he? Ah-ha! say the anti-Catholics. See! It says Peter was in Babylon, not Rome! But was he really in Babylon, the ancient city in Mesopotamia? Probably not. Alexander the Great conquered Babylonia, and the city of Babylon, in 333 B.C. (and died there). Following Alexander’s death, his vast conquests were divided between his leading generals. Seleucus took Babylonia, and founded the Seleucid Empire, with its capital at the newly-founded city of Seleucia. From that time on, the city of Babylon was in decline, until by the first century A.D. it was mere ruins. The Greek historian Diodorus Siculus (ca. 50 B.C.) attests:

But all these [temple treasures] were later carried off as spoil by the kings of the Persians, while as for the palaces and the other buildings, time has either entirely effaced them or left them in ruins; and in fact of Babylon itself but a small part is inhabited at this time, and most of the area within its walls is given over to agriculture. (The Library of History 2.9.9, ed. by C.H. Oldfather)

Peter would have no reason to be in the literal Babylon. Further, Peter writes as someone under the authority of the emperor (cf. 1 Peter 2:13–17), and as one experiencing the thick of Christian persecution (cf. 1 Peter 4:12, “the fiery trial”), when the first major Christian persecutions began in the city of Rome under Nero — and Mesopotamia was not yet under Roman rule in the first century. But if not the literal Babylon in Mesopotamia, where else might “Babylon” be?

The Beast seated on seven mountains

The Revelation of John refers to Babylon:

And I saw a woman sitting on a scarlet beast which was full of blasphemous names, and it had seven heads and ten horns. The woman was arrayed in purple and scarlet, and bedecked with gold and jewels and pearls, holding in her hand a golden cup full of abominations and the impurities of her fornication; and on her forehead was written a name of mystery: “Babylon the great, mother of harlots and of earth’s abominations.” And I saw the woman, drunk with the blood of the saints and the blood of the martyrs of Jesus. When I saw her I marveled greatly. But the angel said to me, “Why marvel? I will tell you the mystery of the woman, and of the beast with seven heads and ten horns that carries her. … This calls for a mind with wisdom: the seven heads are seven mountains on which the woman is seated; they are also seven kings, five of whom have fallen, one is, the other has not yet come, and when he comes he must remain only a little while (Revelation 17:3–5, 7, 9–10).

Map of Ancient Rome, showing the Seven Hills.

In this, John tells us quite clearly where, at least in his symbolism, Babylon is: A city arrayed in purple and scarlet, bedecked with gold and jewels, the mother of earth’s abominations, drunk the blood of the martyrs and saints of Jesus — and seated on seven mountains. One of the traditional marks of the city of Rome is that it was founded on Seven Hills (called in Latin montes, “mountains” — of which, for what it’s worth, the Vatican is not one; the Vatican was outside the walls of ancient Rome). And no other city in the time of the Apostles would have been such a visible image of decadence and extravagance, the capital of a great empire, the seat of fornication and abomination. As the Roman historian Tacitus remarked, it is in Rome “where all things horrible or shameful in the world collect and find a vogue” (referring, ironically, to Christianity). No other city in Peter’s day would have been more “drunk with the blood of martyrs and saints” — the author of the first great persecutions under the emperors Nero (which Tacitus wrote to describe).

But what of the “seven kings”? Can this also be understood to refer to Rome? Quite easily. It even supports an earlier dating of the Revelation than some have supposed, perhaps around the time of Peter’s martyrdom. First-century Rome was ruled by emperors, of whom the most aggressive enemy of Christians was Nero. This post is already too long, but I will allow the good Jimmy Akin to present for you compelling evidence identifying these seven kings and the Beast of Revelation: [Part 1] [Part 2]

It will suffice to say for now that there is very good reason for identifying the “Babylon” of Revelation with Rome — as even anti-Catholics do when they suppose that Catholic Church is the “whore.” If this was the attitude toward Rome in the first century, it would have been one with which Peter was well acquainted. Indeed, no other first-century city could have so aptly resembled the ancient Babylon: the capital of the civilized world, and of a great and mighty empire; the center of decadence and extravagance and idolatry. Peter has just informed us, without a doubt, that he is in Rome.

As does my son Mark

And so does my son Mark. In Peter’s closing, he also identifies for us two of his companions who are by his side in “Babylon.” Can this shed any light on Peter’s whereabouts?

Scripture mentions this Mark, the author of the Gospel of Mark, in a number of other places. When Peter was freed from the prison of Herod:

Peter came to himself, and said, “Now I am sure that the Lord has sent his angel and rescued me from the hand of Herod and from all that the Jewish people were expecting.” When he realized this, he went to the house of Mary, the mother of John whose other name was Mark, where many were gathered together and were praying (Acts 12:11–12).

So we see an association between Peter and Mark from the earliest days of the Church, attested to in Scripture.

Later in the same chapter, we find Mark accompanying Paul and Barnabas on Paul’s second missionary journey:

The word of God grew and multiplied. And Barnabas and Saul returned from Jerusalem when they had fulfilled their mission, bringing with them John whose other name was Mark (Acts 12:24–25).

But as they set out for their next journey, Paul and Barnabas had a disagreement over Mark:

And after some days Paul said to Barnabas, “Come, let us return and visit the brethren in every city where we proclaimed the word of the Lord, and see how they are.” And Barnabas wanted to take with them John called Mark. But Paul thought best not to take with them one who had withdrawn from them in Pamphylia, and had not gone with them to the work. And there arose a sharp contention, so that they separated from each other; Barnabas took Mark with him and sailed away to Cyprus, but Paul chose Silas and departed, being commended by the brethren to the grace of the Lord (Acts 15:36–40).

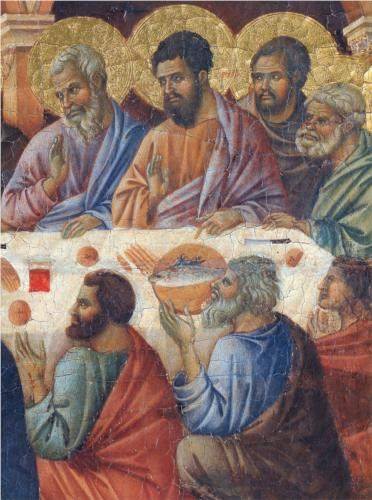

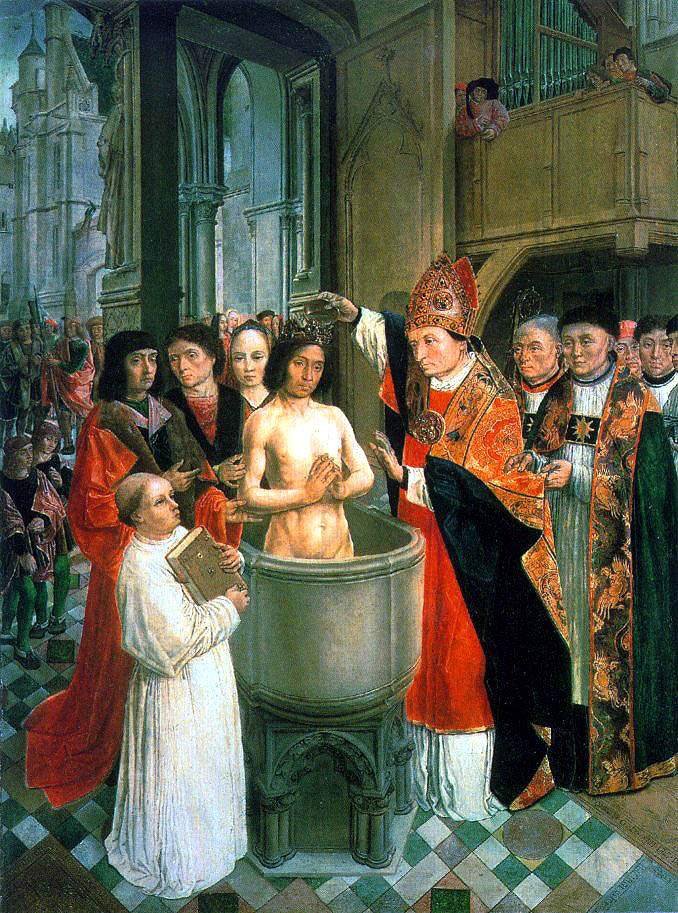

St. Peter Preaching in the Presence of St. Mark (c. 1433) (WikiPaintings).

Now this is important: Barnabas and Mark leave the scene, and Paul takes on a new companion, Silas — also known as Silvanus (cf. Acts 17:15, 18:5; 2 Corinthians 1:19; 1 Thessalonians 1:1; 2 Thessalonians 1:1).

Paul and Mark later reconciled. We next find Mark as a companion of Paul at the time of his writing the epistles to the Colossians and to Philemon:

Aristarchus my fellow prisoner greets you, and Mark the cousin of Barnabas (concerning whom you have received instructions—if he comes to you, receive him), and Jesus who is called Justus. These are the only men of the circumcision among my fellow workers for the kingdom of God, and they have been a comfort to me (Colossians 4:10–11)

Epaphras, my fellow prisoner in Christ Jesus, sends greetings to you, and so do Mark, Aristarchus, Demas, and Luke, my fellow workers. (Philemon 23–24)

We find in these letters that Paul is a prisoner. This is his first captivity — in Rome (cf. Acts 28:16).

Scholars date Paul’s first imprisonment in Rome, and the authorship of these letters, to the spring of A.D. 61 through the spring of A.D. 63 — which also happens to be the range of dates commonly ascribed to the authorship of the first epistle of Peter. So we have, direct from Paul in Scripture, testimony to the fact that Mark was in Rome. And if Mark was in Rome during that time, and was with Peter when he wrote his letter, then it is reasonable to conclude that Peter was also in Rome.

But what of Silvanus? Scripture makes no mention of him following Paul’s third missionary journey (Acts 18:5) — until we find him by Peter’s side in 1 Peter. But as Silvanus was a constant companion of Paul, it would be reasonable to assume that he at least visited Paul in Rome, if not moved the base of his apostolic operations there. The presence of Silvanus by Peter’s side, too, supports the conclusion that Peter was in Rome.

You will stretch our your hands

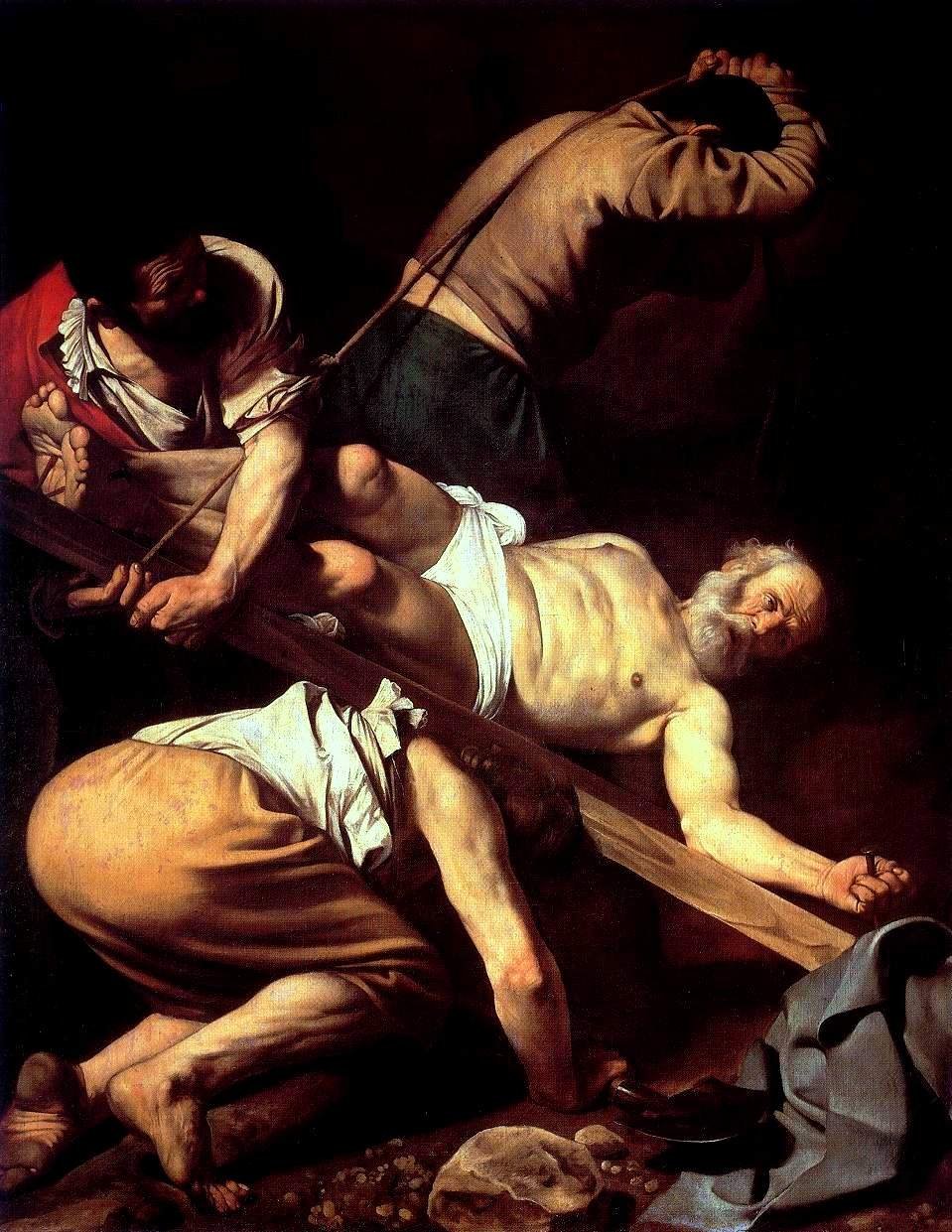

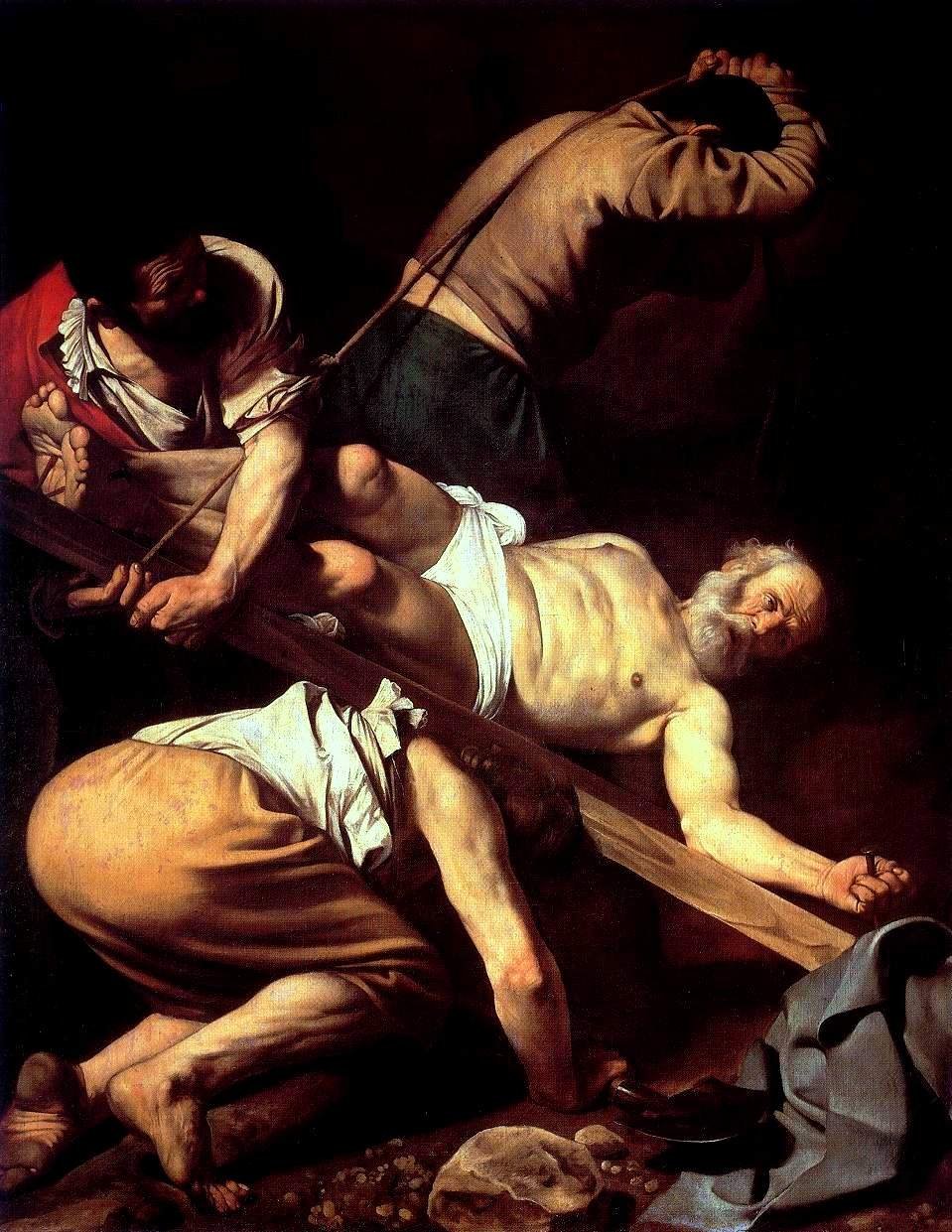

The Crucifixion of St. Peter (1600), by Caravaggio (Wikipedia).

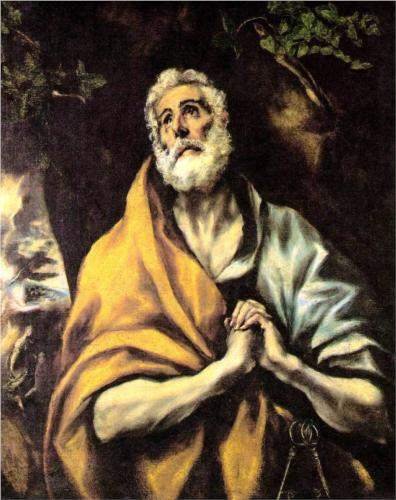

We have one parting testimony to the end of Peter’s life — in the Gospel of John, widely held to have been one of the last-written books of the New Testament — certainly after the death of Peter:

Jesus said to him, “Feed my sheep. Truly, truly, I say to you, when you were young, you girded yourself and walked where you would; but when you are old, you will stretch out your hands, and another will gird you and carry you where you do not wish to go.” (This he said to show by what death he was to glorify God.) And after this he said to him, “Follow me.” (John 21:18–19)

You will stretch out your hands. In the ancient world — particularly in the Christian tradition — “to stretch out one’s hands” was an almost explicit reference to crucifixion. Indeed, to John the author, this language is meant to be clear to the reader: “This he said to show by what death [Peter] was the glorify God.” Certainly by the time of the writing of John’s Gospel, Peter’s martyrdom had already occurred — so if this were not a true description of Peter’s death (the details of which his readers would have known well), he would not have included it. Further, for Peter’s death to have been by crucifixion, he would have to have been living under Roman rule, since crucifixion was the Roman method of execution: this would not have been the case had he been living in Mesopotamia.

Indeed, the whole tradition of the Church affirms that this was the manner of Peter’s death:

Come now, you who would indulge a better curiosity, if you would apply it to the business of your salvation, run over the Apostolic churches, in which the very thrones of the Apostles are still pre-eminent in their places, in which their own authentic writings are read, uttering the voice and representing the face of each of them severally. . . . Since, moreover, you are close upon Italy, you have Rome, from which there comes even into our own hands the very authority [of Apostles themselves]. How happy is its church, on which Apostles poured forth all their doctrine along with their blood! Where Peter endures a passion like his Lord’s! Where Paul wins his crown in a death like John [the Baptist]’s [and] where the Apostle John was first plunged, unhurt, into boiling oil, and thence remitted to his island-exile! (Tertullian, Prescription against Heretics 36, ca. A.D. 180-200)

Thus publicly announcing himself as the first among God’s chief enemies, [Nero] was led on to the slaughter of the apostles. It is, therefore, recorded that Paul was beheaded in Rome itself, and that Peter likewise was crucified under Nero. This account of Peter and Paul is substantiated by the fact that their names are preserved in the cemeteries of that place even to the present day. (Eusebius of Caesarea, Church History II.25.5, ca. A.D. 290)

So we see that Scripture is plain in testifying to the ministry and death of Peter in Rome. Even those of a sola scriptura mindset should be satisfied. There is no sense in denying that Peter lived and died in Rome — to which the unanimous voice of the Church Fathers and other early writers of the Church testifies, dating to before the close of the first century, and which findings of archaeology confirm. If anyone would deny the truth of the Catholic Church, they must do so on other grounds than the historical.