This is a bit heavier than my usual posts here, but it answers an important question that Protestant apologists have posed to me and other Catholic converts: Was I only drawn to the Catholic Church because its claims to authority offered an “easy out” to the difficulties of weighing Scripture and doctrine for myself?

Paralysis

A Catalogue of the Severall Sects and Opinions in England and other Nations: With a briefe Rehearsall of their false and dangerous Tenents. Broadsheet. 1647.

I’ve been accused before, and I readily admit that it’s true, that as a Protestant, I never had a very thoroughgoing commitment to Protestant theological principles. It was not for lack of trying: for a number of years I had studied theology, prayed, and pored over the Scriptures in an earnest attempt to arrive at some apprehension of the truth. But no Protestant theology, despite the ardent, sometimes vehement assertions of each’s adherents, had a firm enough foundation to convince me. Each was based in subjective interpretations of the Scriptures that lacked either the context or the clarity to convey everything their doctrines demanded of them. Each’s interpretation conflicted with every other, and yet was based in the very same texts; and each had no greater claim to being the correct and sole interpretation of those texts than the rest. I had not the knowledge or the faculty to sort it all out, and even if I had, any conclusion I reached would be, I realized, my own subjective conclusion, based only on my own interpretation and whosever opinion happened to sway me at that time. I realized the inherent weakness, instability, and insufficiency of this position. Though I would never have articulated it this way then, it was clear that Scripture by itself could not teach me everything I needed to know about God and His salvation.

So as a Protestant, I resigned myself to uncertainty, to never being sure exactly what Scripture was trying to teach; to never knowing, in the sea of competing and conflicting doctrines, which ones were the true ones. Since I could not discern, from Scripture, the truth or falsehood of every doctrine and theology, I was lulled into a sense of complacency, what I called a thoroughgoing ecumenism: if I could discern no school of theology to be absolutely true, then each of them must be more or less acceptable and worthy of consideration. On one hand, I am glad for this: it made me tolerant and accepting of a wide diversity of Christian brothers and sisters, and open-minded enough to listen to and consider what they have to say. It was an open-mindedness that eventually made me willing to examine the Catholic Church and finally found welcome in her walls. It troubled me, and still does, the Protestants who could assume a stance of enough certainty to condemn and judge the doctrines of other believers, based on so unsteady a foundation as I perceived theirs to be. On the other hand, this ecumenism eventually reached a point of doctrinal relativism, agnosticism, or universalism: that not only could we not know the truth of doctrine, but that it didn’t really matter and that God loved and accepted us all anyway.

A Protestant apologist recently referred to this as the “paralysis” of the Protestant mind; apparently it is common enough to have its own name. This apologist also suggested, as I have heard other Protestant apologists charge against other Catholic converts, that the Catholic Church was attractive to me simply because it offered a way to break this “logjam”: that I accepted the Church’s claims only because they asserted a singular authority, because the Church could dictate the answer rather than leave me to muddle it out on my own, and not because there was anything compelling or convincing about the claims of themselves: in short, that the singular, magisterial authority of the Catholic Church was a crutch, an escape, a deus ex machina, an easy out of the Protestant conundrum of having to reason through the Scriptures.

There are several answers I’d like to make to this charge.

I resisted until I couldn’t

First, I wasn’t looking for such a crutch. I was well aware of the position of the Catholic Church in claiming to be the only authoritative interpreter of Scripture for years before I ever considered Catholicism — and rather than being an attractive prospect, it horrifed me more than almost anything else I knew about the Church. It seemed the perfect setup for the many doctrinal abuses I had heard about and believed existed in Catholicism: if the Church can dictate that some thing in Scripture means something different than what it says, and that doctrines don’t even have to have a biblical basis at all, then she can teach her followers anything, no matter how contrary to reason and truth, and compel them to accept and believe it. (Of course, these are all mischaracterizations of what the Church teaches.) As an academic, I cared about and was convinced by reason and evidence, and was suspicious of claims without solid factual foundation. The Catholic teaching authority, as I understood it, was a proposition that I strongly and vehemently resisted, not one that I readily embraced as a savior.

“Authority” in a Different Sense

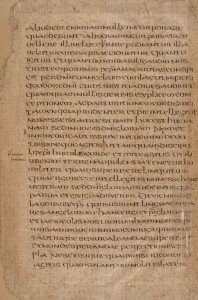

Leaf from a manuscript of Augustine at the Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris, dated c. 7th–8th century (e-codices.unifr.ch).

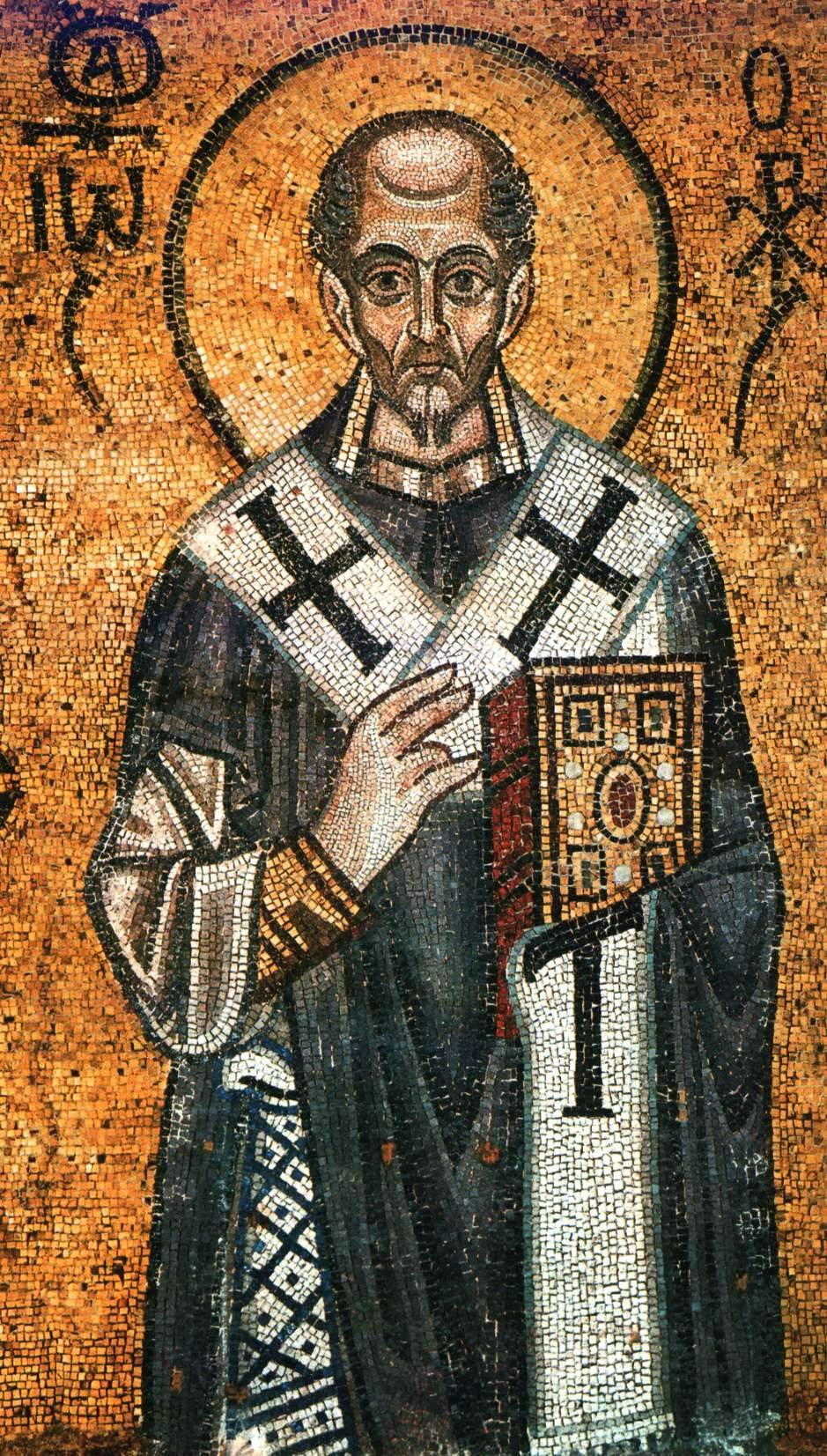

Once I examined her in earnest, the Catholic Church won me over, against my expectations or inclinations, because her arguments were compelling: not merely because they claimed to be authoritative, but because they were based on actual authority, on an authentic, continuous, and documented tradition of authoritative testimony. Protestants tend to think of “authority” only in terms of divine authority, the absolute, unquestionable authority of God, which they find solely in Scripture. In this regard — even if they acknowledge that Jesus granted authority to His Apostles — they find no essential connection between that authority and the Church, and so presume that the claims of the Catholic Church to be “authoritative” are based only on bald assertion. But to me as an historian, “authority” also has another meaning: the authority of support for a claim or argument. And rather than bald assertions or empty, unsupported claims, as I had been led to believe the Catholic Church stood on, I found, for every substantive point of Catholic doctrine, well-articulated, well-defined, and well-supported arguments based in a rich, academic, scholarly tradition and founded on a continuous and consistent corpus of authoritative documents and teachings spanning twenty centuries.

The Catholic Sense of Scripture

In most everyday matters, it is precisely this latter understanding of authority that is the substance of Catholic teaching, and not the sort of dictatorial pronouncements that Protestants presume. For example, Protestants commonly understand that the Catholic Church must dictate to the believer how to interpret every jot and tittle of every passage of Scripture, such that believers cannot read and interpret Scripture for themselves. But the truth is that the Church has given authoritative teachings on only a very small portion of the whole corpus of Scripture. The sense of the Catholic understanding of Scripture subsists not only in such pronouncements, but in the exegetical tradition of Church Fathers, bishops, teachers and theologians, whose mind and understanding is faithfully passed down and preserved in the Church — whose teaching is authoritative by its own merit, because of their great learning and holiness and their nearness in history to Christ’s revelation. Though not having divine authority on its own, this is more authoritative by bounds than the subjective, substantially unsupported interpretations of Protestants.* In exactly the same way, I accept the writings of past historians as having great knowledge and insight, as being authorities into their subject matter.†

* There are some Protestants, especially the great theologians, who do seek to support their exegetical arguments with appeals to the authority of the Church Fathers; but generally, I find, they do this selectively and unevenly, accepting a Father’s argument where it suits them but ignoring him where it does not, and looking to the Fathers only as a last recourse, designed to support their own subjective interpretation, and not as a primary means to discerning the meaning of the Scriptures in the first place.

† Of course, some historians are simply wrong; and Church Fathers can also be wrong. Here the consensus of the Church, the opinions of other Fathers and teachers and theologians, is important. If the consensus of later writers is that Augustine was a great and orthodox teacher, then that is the reputation and the authority he enjoys. If the consensus is that Tertullian strayed off track in his later life and expressed some opinions that are not in agreement with the Church’s teachings, then we read those opinions of Tertullian as dissenting and sometimes heterodox arguments. Nevertheless, because of his position in time, so close to the Apostles themselves, Tertullian’s authority as an historical witness to the doctrines believed and taught in his time is absolute.

Teaching from the Deposit of Faith

Matthias Burglechner, The Council of Trent, 16th century (Wikimedia Commons).

This is the raw material: Scripture and the generations of holy men and women who taught, prayed, and commented on it, preserving and passing on the teachings they had received, the inheritance of the faith delivered once unto the saints, and with it the teaching of Christ and the Apostles themselves. When the Catholic Church does make official pronouncements of doctrine — whether from a council of bishops or pastorally from the pope — these teachings are not invented from nothing, but are drawn from, based on, and supported by this raw material. Especially when the meaning of Scripture and doctrine is not completely clear from the sources themselves, and when there is uncertainty or dispute, it is the role of the Church’s Magisterium, her teaching authority, to weigh the body of evidence and discern the truth from it. Even then, the conclusion is not arbitrary: the Magisterium cannot declare something contrary to the evidence, contrary to Scripture or to the orthodox teachers of the faith; she cannot declare a circle square, or dictate something that revelation has not itself revealed, or compel her faithful to believe something not already contained in the deposit of faith. The Church teaches what she has received (1 Timothy 4:11): not anything more and not anything less.

A Well-Built Building

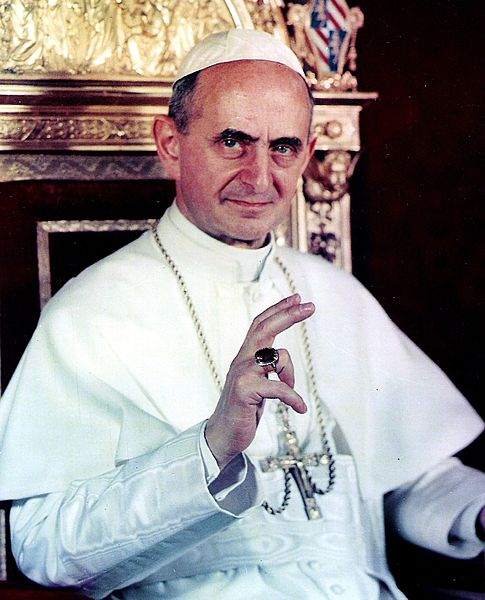

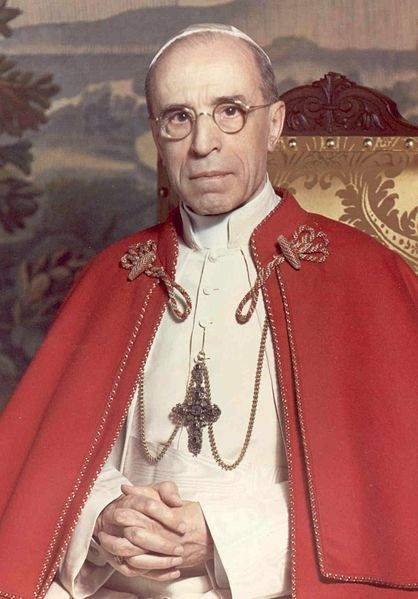

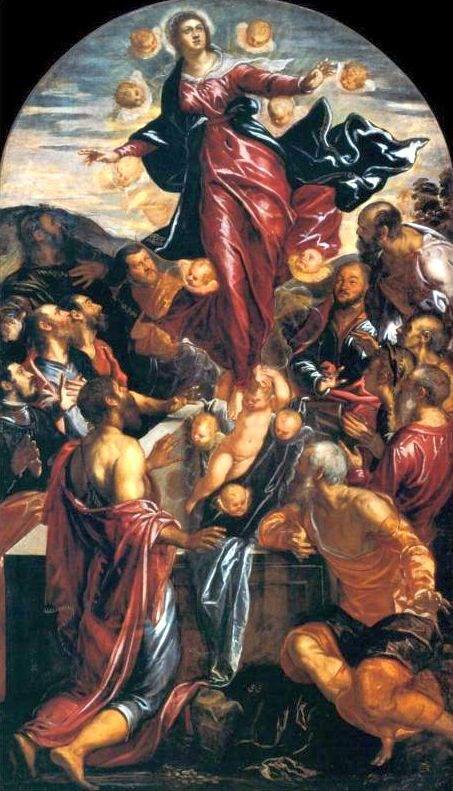

Catholics believe that in such teachings, the Holy Spirit guides the Church into all truth (John 16:13) — and this is a simple matter to believe, because they are evidenced by the constant and unchanging course of that guidance, and founded in reasonable and well-supported arguments from authority. For example: the Catechism of the Catholic Church, the epitome of Catholic doctrine, is not a book of empty assertions, but bases its every sentence on several thousand citations to authority in Scripture, the Church Fathers, councils and popes. Every one of these citations can be followed to find the origin and basis of the Church’s teaching, like a well-built building, every element borne up by the support of another, until it reaches the ground of absolute authority in Christ’s revelation itself. Even the declarations of the most controversial doctrines to those outside the Church, such as the dogma of the Assumption of Mary in Pope Pius XII’s 1950 Apostolic Constitution Munificentissimus Deus, rest not on bald assertion or any empty claim to papal privilege or authority, but on carefully constructed and well-reasoned arguments from the tradition of received authority.

Thus, the charge that I was drawn to the Catholic Church solely because her claims to authority were a cure for my exegetical paralysis, a crutch and an escape from having to discern and decide for myself, is completely false. The Catholic Church did cure my exegetical paralysis, but I was not seeking and did not believe there could be a cure: I was taken by surprise, and thoroughly convinced, by something I was not expecting at all, something I never imagined could exist: a Christian body who based its arguments not on subjective interpretations of Scripture, not on concepts and constructs of theology with no other basis than such interpretations, not on vitriolic polemics against other sects — but on the very concepts of authority, evidence, and tradition I had been taught to embrace and accept as an academic; on a sturdy and unshakeable foundation of such authority reaching back through the ages to the Apostles themselves, evincing and confirming the origin of all authority, Christ Himself.