I’ll be honest: I’m not sure about this post. It comes across as more critical than I meant it to be. I do not mean to “bash” anyone’s faith; only to point out what I see to be honest, practical difficulties in particularly Evangelical Protestantism, as I’ve witnessed and I myself experienced. As usual, if I miss the mark on something, please call me on it.

Reading back over my recent posts, there is a point I wanted to touch on but didn’t quite hit in my post on “Catholicism and Assurance of Salvation.”

It is this: Unlike the Evangelical, who might struggle with uncertainty and doubt as to whether he is “really saved,” seeking a “confirmation” of the “assurance” of his salvation — the Catholic can be assured from the very beginning, from the moment of his Baptism, in the promises of Christ, that God’s grace has done what Scripture promises it will do: that his every sin has been washed away (Acts 22:16); that he has been born again in Christ (John 3:3,5; Romans 6:3–6; Titus 3:5); that he has received God’s Holy Spirit (Acts 2:38, 19:5–6). From the moment he receives absolution in the Sacrament of Confession, he can be sure that God has forgiven his sins (1 John 1:9), that he has been healed and restored in grace (James 5:15), because this is what Scripture promises. From the moment he receives the Lord in the Holy Eucharist, he can be sure that he has encountered Christ, Body and Blood, Soul and Divinity (1 Corinthians 10:16), and that His grace and eternal life have flooded his soul (John 6:54) — because this is what Jesus Himself promised.

From a practical standpoint, speaking as someone tending to approach situations from the perspective of feeling (I am a textbook INFP) — and, as the other night, having witnessed this in my friends — the Evangelical approach tends to place much emphasis on feelings and emotions: “I have assurance that I am saved because I feel assured.” And vice versa: “I wonder if I am really saved, because I don’t feel it.” Salvation, in this tradition, seems to depend also on our human understanding: I have heard many times, “I thought I was saved; I went to church, was baptized, worked in outreaches, sang in the choir — but then I realized that I didn’t really ‘get it,’ and wasn’t really saved at all.” “Getting it” often depends not only on an intellectual comprehension, but an emotional appreciation. I have heard from so many people — and I can testify to this myself — that “I went down [to the altar call] every week, prayed the ‘sinner’s prayer’ again and again — but I just didn’t feel saved.” “Feeling saved” does not necessarily mean that one is, nor does “not feeling” mean that one is not, but the experience of these feelings certainly has a lot of bearing on one’s assurance and security. The idea of “assurance of salvation” depends on the apprehension of something subjective; something one feels one has or not; something that can be thrown into doubt by sin or scrupulosity.

I suspect this phenomenon is particular to the Evangelical Protestant tradition, possibly only to certain sectors of it, and may have more to do with one’s own scrupulosity and insecurity than anything inherent to the tradition; but that door is very often left open, and I don’t see an easy remedy. Was not Luther’s initial concern his scrupulosity, his not feeling justified? Other forms of Protestantism may or may not suffer from this same problem, or at least not to the same degree. But this emotionalism, this subjectivity, is the extreme end, it seems to me, of one of the basic theological differences between Catholic theology and Protestant theology: differing understandings of the mode of grace working through the Sacraments.

The Workings of Grace

One of the fundamental disagreements of the Protestant Reformation concerns the mode of the working of the Sacraments: how it is that the grace of the Sacraments is accomplished; in what mode the Sacraments are efficacious. According to the Catholic understanding, first formulated by the medieval scholastic theologians, the Sacraments work ex opere operato, “from the work having been worked”: the efficacy of the Sacrament comes from the very fact that the work was done (by God). The opposing Protestant view can be summed up as ex opere operantis, “from the work of the one working”: that is, the efficacy of the Sacrament depends upon the spiritual disposition of the one receiving it, namely, upon his faith.

The Catholic view understands the Sacraments to be instruments of God through which He immediately acts upon the believer, conferring His grace — one of the gifts of which is saving faith. One of the major concerns of this doctrine, dating from the earliest centuries of the Church, is that the efficacy of the Sacrament does not depend at all on the holiness of the minister — since God can work through even the instrumentality of a sinful priest. The requirements of the Sacrament are only that it be carried out in the correct matter and form, by a minister with the power and the intention to perform it. The graces of the Sacrament flow from the working of the Sacrament itself. In order for the recipient to receive these graces, he must be properly disposed — e.g. having faith in Christ, sincere repentance, the intention to receive the Sacrament, with no obstacle or impediment to it. But whether he receives the graces or not, they are present, ex opere operato. Thus, the recipient of the Sacrament has the positive expectation that the Sacrament has done what it was supposed to do, what God promised: it does not depend subjectively on either the minister or the recipient, apart from the requirement that they have the necessary disposition — which is more often formulated as a negative: the Sacrament can be presumed to have been valid unless there existed some impediment.

On the other hand, the Protestant view understands the Sacraments to be aids to the mind, which enable it, by faith, to approach God and receive grace. The efficacy of the Sacrament depends solely on the believer’s disposition — that is, on faith alone. Faith is the instrument by which the soul reaches out to apprehend the redemptive work of Christ and procure the grace of justification from God.

Both positions agree that grace comes from God alone. The difference is this: Does God actively and immediately administer grace to the believer through the Sacraments, this grace being efficaciously applied so long as the believer has the proper disposition? Or does the believer, through the Sacraments, reach out to God to obtain His grace by faith? To abstract a step further: Is the immediately active role in justification played directly by God Himself, or by the faith of the believer (which is given by God)? Are we actually justified by faith alone, apprehending salvation, or are we justified by God alone, faith being a necessary disposition, and saving faith itself a work of God? Does God’s grace depend subjectively on the faith of the believer, whether it apprehends the saving work of Christ, or objectively on God’s working alone?

In the case of the Evangelicals with whom this discussion began — they generally have no belief in “Sacraments” at all. Baptism and the Eucharist are merely symbolic acts of faith which convey no grace in and of themselves. But the Protestant principle nonetheless formed a foundation for the Evangelical understanding: Rather than the faith of the believer reaching out to God by means of the Sacraments as aids, his faith reaches out to God with no aid but faith itself. The uncertainty and insecurity of whether faith has apprehended anything at all is thus understandable — like shooting for the moon with only dead reckoning as a guide.

Works’ Righteousness?

Pietro Longhi (1701-1785), The Confession (WikiArt.org).

The doctrine of grace being received from the Sacraments ex opere operato is another target for the common anti-Catholic charge that Catholics believe in “works’ righteousness.” The idea that a believer can be baptized, confirmed, partake of the Eucharist, be absolved in Confession — and out of those works themselves, receive grace — seems to all but confirm the accusation. The believer performs a work in exchange for grace.

But this is a misunderstanding. While it is true that the Sacraments are active in working, it is in fact God alone who works in the Sacraments — the believer only passively receiving His grace. Ironically, it is the Protestant position in which grace depends on the work of the believer (ex opere operantis) — on his faith actively apprehending the grace of Christ’s saving work. It is true that faith is not a human work, but a gift of God — so the charge of “works’ righteousness” does not properly apply to the Protestant view any more than it does to the Catholic. But whether one is “saved,” in the Protestant view, depends on whether the believer has apprehended, by faith, the truths of the Gospel. How the understanding of saving faith is framed can vary widely across traditions, but it seems to be inherently subjective. As seen in the Evangelical experience, being “really saved” can be understood to depend on “really getting it,” that is, truly grasping the message of the Gospel, by the head and by the heart.

This at once presents difficulties: If being “saved” depends on the believer’s understanding — and this view seems to be wider than the Evangelical tradition — for example, I frequently hear charges, particularly from the Reformed, that “Catholics cannot be saved unless they have faith in Christ alone,” to the exclusion of the Sacraments, “works,” etc. — i.e. In this view, salvation depends upon the intellectual understanding of a particular doctrine, and any other understanding can nullify faith in Christ — then how can small children be saved? What about the mentally disabled? What if a person can never apprehend the Gospel by faith at all? I have heard Protestant leaders (notably several prominent Reformed ones) say, flat-out, that children cannot be saved. I do not suppose that all Protestants, or even all Reformed, feel this way — but an understanding of salvation that makes grace dependent on the subjective faith of the believer as an intellectual understanding and emotional appreciation naturally runs into such questions.

Assurance for today

So, to return to the initial, practical concern: The faithful Catholic who participates in the sacramental life of grace has assurance that he is indeed receiving the grace of the Sacraments — for this is what Jesus promised. Despite any charges of “works’ righteousness,” the state of grace in a Catholic depends not on his own working, but objectively on the working of God in the Sacraments, by the saving work of Christ; in contrast to the Protestant, whose assurance is subjective, dependent on whether he has grasped the truths of God by faith. The Catholic’s assurance is not an eternal assurance: he cannot know the future, whether he will have the grace of final perseverance or not; but he has assurance for today, in the daily bread that Jesus provides.

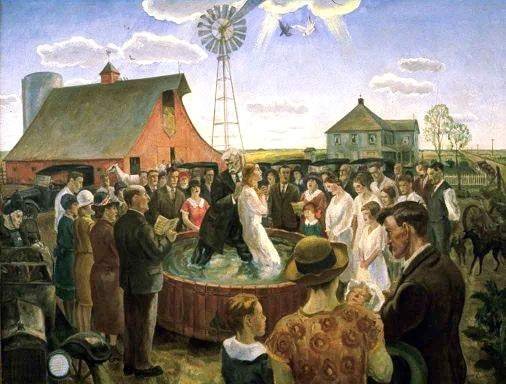

A comment aside: It is really difficult to find artwork to illustrate Protestant theological concepts!