Giuseppe De Fabris. Statue of St. Peter (1840). St. Peter’s Square, Vatican City. (saintpetersbasilica.org)

Nearly every day, consistently, the top-ranking search term for my blog is “tomb of st. peter” or some variant. Every day, this post, about my pilgrimage to the tomb of St. Paul, attracts at least several hits in search of St. Peter, despite only mentioning him in passing (to a relic of St. Peter, his head, being at the Lateran). Clearly there is a great deal of demand for the relics of the Prince of Apostles. I have heard my readers’ cry, and decided to give them what they wanted.

As it happens, this is a topic that fascinates me, too. It combines so many of my favorite things: saints, cemeteries, the Church, ancient Rome, archaeology, and history. I had never studied much about the search for St. Peter’s relics, but it was something I had been wanting to pursue for a long time — since I had stood there at the high altar of St. Peter’s, in fact.

At that time, in 2005, I was something of a skeptic, not yet a searcher. The tomb of St. Paul had been so powerful to me because I had read about the recent archaeological findings. I had faith that Paul was really there. When I got to St. Peter’s however, I knew nothing about the extensive archaeology that had been done beneath the basilica or the provenance of the relics discovered there. I didn’t even understand where exactly the relics were; and I didn’t speak Italian and couldn’t ask. So when I stood there at the altar, peering down into the confessio, I wasn’t quite sure what I was looking at.

What I was looking at was the confessio, the chamber leading down to the tomb. Only those with permission (usually clergy) are allowed to go down these steps, to pray as close as possible to the body of the saint. The niche at the end of the confessio, immediately below the altar, is called the Niche of the Pallia. When in Rome, I thought the silver coffer under the ancient Christ mosaic might contain St. Peter’s bones — but this is actually the chest that contains the pallia, the wool bands which the pope presents to metropolitan bishops as a symbol of delegated authority. The night before the pallium ceremony, the vestments are placed here overnight, that St. Peter, chief of all bishops, might bless them.

The niche had been here, like so, for centuries, longer than anyone could remember. Even before that, there had been generations of successive popes who had remodeled the altar area. The tradition had always been, since time immemorial, that St. Peter was buried beneath the high altar — but it had been ages since anyone had laid eyes on the tomb, and no one knew exactly what was down there.

In 1939, following the death of Pope Pius XI, the Vatican had decided to expand the Grottoes under the basilica in preparation for the pope’s burial. To make room for the additions, they needed to lower the floor. As soon as workmen started digging, they began uncovering marble sarcophagi — burials that over the ages had been lowered through the floor (which had been at the level of the original floor of Old St. Peter’s). This wasn’t cause for particular concern; they set them aside. But then, within a few months of beginning work they struck something — masonry. Old masonry, older than anything that should have been there. Hastily, the workmen summoned the Vatican archaeologist. Very carefully, they exposed what proved to be an ancient mausoleum, without its roof.

The ancient tradition is that the emperor Constantine had built St. Peter’s on top of an ancient, pagan necropolis, in which St. Peter had been buried following his martyrdom, to venerate the grave of the Apostle. The Vatican archaeologists soon uncovered the truth of this: a long avenue lined with some two dozen ancient, pagan tombs, dating certainly to the second and third centuries and possibly even older. Though most of the oldest tombs were pagan, the later ones showed evidence of increasing Christian burials. A number contained remarkable artwork.

Diagrams showing the location of the excavations under St. Peter’s Basilica, along the natural slope of Vatican Hill, which Constantine had leveled in construction of the original basilica, burying the necropolis. (Walsh)

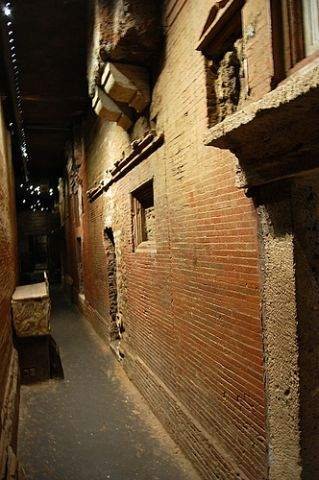

St. Peter’s Basilica was built on the side of the Vatican Hill. Not only does the slope of the hill rise from east (the façade of the church) to west (the apse), but at an even steeper incline, it also rises from south to north. The ground had to be built up considerably to lay an even foundation for the church, and in the process the builders simply removed the roofs of the necropolis’s tombs, packed dirt into the chambers, and used the walls as supports. In the process they preserved them, and left a considerable portion of the ancient cemetery sloping down underneath the church. Over the ensuing months and years, archaeologists painstakingly excavated as much as they could. The corridor of the necropolis, with tombs on both sides, extends some sixty meters beneath the Grottoes. The original necropolis was probably even larger, but the excavators were limited by how much they could uncover without undermining the foundations of the church: Constantine erected six great retaining walls into the hillside, running the length of the church, and no doubt slicing through the cemetery.

Initially reluctant, Pope Pius XII granted permission for the archaeologists to investigate beneath the high altar. Breaking through the rear wall of the Clementine Chapel, they discovered a wall of ancient marble trimmed with porphyry — which proved to be the back of the ancient memoria Constantine had erected around St. Peter’s tomb.*

* This description presupposes a lot that the archaeologists only understood after years of excavation, interpretation, and reconstruction. Initially, they had only a vague idea what they were looking at.

According to the historian Eusebius, writing in the 290s, Saints Peter and Paul were both martyred in Rome under the persecution of Nero, ca. 63–67. Eusebius attests that “this account . . . is substantiated by the fact that their names are preserved in the cemeteries of that place even to the present day.” He cites as testimony a disputation published by Gaius, a churchman under Pope Zephyrinus (r. 199–217), against Proclus, an early Montanist leader. When Proclus appealed to the tombs of St. Philip and his daughters at Hierapolis to substantiate the apostolic tradition of his teaching, Gaius replied, declaring the superiority of Rome’s apostolic tombs (Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History II.25):

But I can show the trophies of the apostles. For if you will go to the Vatican or to the Ostian way, you will find the trophies of those who laid the foundations of this church.

Eusebius, writing some forty years before Constantine began work on St. Peter’s Basilica, here confirms the tradition that St. Peter was buried on the Vatican, and that St. Paul was buried along the Ostian Way, where Constantine also built the Basilica of St. Paul Outside the Walls. Their tombs were still well known in Eusebius’s day. By Gaius’s testimony, the tombs were certainly being venerated from an early date. It is from this passage that the archaeologists came to identify the ancient monument they discovered over St. Peter’s grave, preserved inside Constantine’s memoria, as the Tropaion (τρόπαιον, or “trophy”) of Gaius.

The Tropaion, as archaeologists discovered it inside Constantine’s memoria and reconstructed it, is believed to have been erected under the reign of Pope Anicetus, between 150 and 167 (this dating from some marked bricks found in the area and from a reference in the Liber Pontificalis regarding the pope who “built the monument of the blessed Peter,” who is identified mistakenly with Pope Anacletus). The archaeologists were able to reconstruct, by the many other graves nearly, layered upon each other — likely Christians who wanted to lie near St. Peter — a history of the grave, dating back certainly, they argued, to the latter half of the first century when Peter would have been buried.

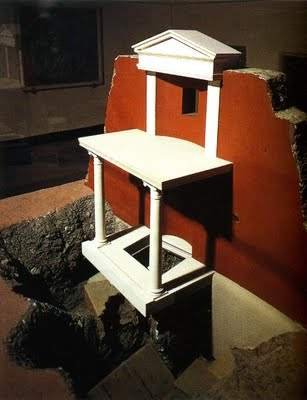

A model of the way the Tropaion would have appeared ca. 260, after the construction of the Graffiti Wall. (mcsmith.blogs.com)

Sometime in the mid-third century, around the decade of 250–260, a major break occurred in the supporting wall behind the Tropaion (the famous “Red Wall” of the excavation). A thick sustaining wall was built against the north side of the Tropaion, upsetting its aesthetics considerably but supporting the structure. This wall, when archaeologists discovered it, had come to be covered with the graffiti of pilgrims. Another wall was eventually built on the south side. This is the way the monument would have appeared in the time of Constantine.

A model of Constantine’s memoria, circa fourth century. The clear shelf at the top of the model corresponds with the floor of the modern-day basilica. (mcsmith.blogs.com)

The rear of Constantine’s memoria. Compare to the rear wall of the Clementine Chapel (see link above). (mcsmith.blogs.com)

Constantine laid the foundations of St. Peter’s basilica between 326 and 333. In leveling the Vatican Necropolis, a cemetery still in active use, he violated Rome’s most sacred laws against the desecration of graves; it would have taken all his imperial authority to avoid censure. But honoring the Christian Apostles was a higher call. It is likely that Pope Sylvester confirmed the location of St. Peter’s grave, under his protection, to Constantine.

In the same way he had done at the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem, Constantine venerated St. Peter’s tomb by breaking down everything around it and encasing it in a marble shell, the memoria. He left the Tropaion intact exactly as it was, even with the unaesthetic graffiti wall. In the original basilica, the memoria stood at the floor level of the church, with the altar set up before it.

Pope Gregory the Great (r. 590–604) conducted a major remodeling of the high altar area of St. Peter’s Basilica during his papacy. He wanted to celebrate Mass on an altar above St. Peter’s tomb — which he placed on top of Constantine’s memoria. In order for the altar to be at the proper level, Gregory raised the floor around the altar, and created the beginnings of the recessed confessio beneath it, and a crypt behind it (which would become the Clementine Chapel).

Later popes would make further additions and improvements. Popes Callixtus II (r. 1119–1124) and Clement VIII (r. 1592–1605) both installed new high altars. Gradually Constantine’s memoria and St. Peter’s tomb were lost from view and memory. St. Peter’s tomb was here, tradition assured the Church; but nothing more was known for certain, than that the Apostle lay beneath the high altar.

The Niche of the Pallia, in the confessio of the present church, rests in the portal of Constantine’s ancient memoria. Immediately beneath it lies St. Peter’s tomb.

That’s enough for one bite! Stay tuned for Part Two, concerning the excavation of the Tropaion: “The Grave of St. Peter.” And the conclusion in Part Three, concerning the relics supposedly belonging to St. Peter, “The Bones of St. Peter.”

- Kirschbaum, Engelbert, S.J. The Tombs of St. Peter and St. Paul. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1959.

- Walsh, John Evangelist. The Bones of St. Peter. New York: Doubleday, 1982.

Pingback: Question - Christian Forums

Pingback: The Grave of St. Peter « Catholicus nascens

Pingback: The Bones of St. Peter « Catholicus nascens

Pingback: Early Testimonies to St. Peter’s Ministry in Rome « Catholicus nascens

Pingback: What is a Saint? « The Lonely Pilgrim

Pingback: Seeing the Pope « The Lonely Pilgrim

Pingback: On this Rock: An Analysis of Matthew 16:18 in the Greek « The Lonely Pilgrim

Utterly compelling- thank you!

Thank you. 🙂 It’s one of my favorites, too. I read two books on it in about two weeks — so, so enthralling. It amazes me that the archaeologists reconstructed the history of the gravesite so completely about 1,600 years after it was basically paved over.

Pingback: The Roman Catholic Controversy: Claims of Authority « The Lonely Pilgrim

Pingback: Of good report « The Lonely Pilgrim

Pingback: Pope St. Gregory the Great « The Lonely Pilgrim

Pingback: What is a Saint? An Introduction for Protestants « The Lonely Pilgrim

Pingback: Some Answers to Common Protestant Objections to Peter’s Ministry as Bishop of Rome | The Lonely Pilgrim

Pingback: Getting it right and wrong: St Peter | All Along the Watchtower

Pingback: Biblical Testimony to St. Peter’s Ministry and Death in Rome | The Lonely Pilgrim

Pingback: On the so-called “Jerusalem Tomb of St. Peter” | The Lonely Pilgrim