The Assumption of the Virgin (1670), by Bartolomé Esteban Murillo. (WikiPaintings.org)

Today is the Feast of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary, celebrating the Assumption of Mary into Heaven. We Catholics believe that at the end of her earthly life, the Blessed Virgin was assumed body and soul into Heaven. The Assumption is one of the most controversial Catholic doctrines to Protestants, since it is one of the most poorly understood, one of the least obvious from Scripture, and one of the latest dogmata to be defined. Pope Pius XII declared the Assumption a dogma in 1950; but that doesn’t mean that Catholics (or Orthodox) just recently made it up. The Feast of the Assumption has been celebrated in the East since around the beginning of the seventh century (ca. A.D. 600), and was celebrated in the West by that century’s end. (In the Eastern Orthodox Church, the Assumption is known as the Dormition, or the going-to-sleep.) Belief in the Assumption is documented in apocryphal eastern texts as early as the third century; there were likely even earlier texts that don’t survive. And the idea has developed over the centuries in scriptural exegesis and in theology. It would take a while to give a thorough defense of the doctrine, but in this article I’d like to offer a few texts that demonstrate the doctrine’s ancient origin.

The Reason for the Assumption

The Assumption of the Virgin (1627), by Anthony Van Dyck. (WikiPaintings.org)

The bottom line, theologically, of our belief in the Assumption is a logical progression: we believe, as the Church has since the very earliest days, that Mary was a perpetually a virgin and preserved from sin in her earthly life. We believe that by the prevenient grace of her Son Jesus Christ, she was immaculately conceived free from the stain of original sin. This gift was not on account of any merit of her own, but only of Christ’s overabundant grace and love for His obedient handmaiden and Mother. Mary was the firstfruits of Christ’s salvation: Just as He saves us and cleanses us from original sin through our Baptism, He saved Mary and cleansed her from the moment of her conception. Therefore, because she did not see the corruption of sin in her earthly life, her earthly body was not subject to the corruption of decay and the grave. The all-holy vessel that bore our Savior and hers into this world — the Ark of the New Covenant, as the Fathers hailed her — could not lie in any earthly tomb. And so at the end of her earthly life, Christ bore her to be with Him in Heaven.

Assumption of the Virgin (1580), by Guido Reni. (WikiPaintings.org)

I used to think that the Assumption of Mary was just a fanciful story, the product of the Church’s overactive Marian imagination, a belief entirely extraneous to the Gospel of Christ. But today the Mass, and Father Joe’s homily, drove home to me how essential it is, and how precious and how beautiful. Mary’s Assumption doesn’t just mean that there’s something special about Mary. Even more important, it means there’s something special about us, about humanity; something worth saving even in this corruptible flesh of ours. It wasn’t mere coincidence that Pope Pius declared the Assumption dogma in 1950, to a despondent world that had witnessed the horrors of war, the depths of cruelty, genocide, and mass destruction. The world at that time needed to be reminded that there is something worth saving in us; there is something lovable and redeemable in humanity: the potential for peace and love and goodness and wholeness, not just depravity and hate. Just as Mary was saved and filled with grace, we too are called to be saved and filled with grace. Just as Mary was assumed body and soul into Heaven, we too are promised eternal life and bodily resurrection on the last day. Mary is the mark of that promise. Because of the grace poured out on Mary, we have assurance of the glorious future that awaits us also.

I can’t put it more perfectly than the liturgy of the Mass today:

It is truly right and just, our duty and our salvation,

always and everywhere to give You thanks,

Lord, holy Father, almighty and eternal God,

through Christ our Lord.

For today the Virgin Mother of God

was assumed into heaven

as the beginning and image

of Your Church’s coming to perfection

and a sign of sure hope and comfort to Your pilgrim people;

rightly You would not allow her

to see the corruption of the tomb

since from her own body she marvelously brought forth

Your incarnate Son, the Author of all life.

In Scripture

The key scriptural text that demonstrates to us the Assumption is in Revelation:

Then God’s temple in heaven was opened, and the ark of his covenant was seen within his temple. . . . And a great sign appeared in heaven: a woman clothed with the sun, with the moon under her feet, and on her head a crown of twelve stars. She was pregnant and was crying out in birth pains and the agony of giving birth. And another sign appeared in heaven: behold, a great red dragon, with seven heads and ten horns, and on his heads seven diadems. His tail swept down a third of the stars of heaven and cast them to the earth. And the dragon stood before the woman who was about to give birth, so that when she bore her child he might devour it. She gave birth to a male child, one who is to rule all the nations with a rod of iron, but her child was caught up to God and to his throne, and the woman fled into the wilderness, where she has a place prepared by God, in which she is to be nourished for 1,260 days. . . .

And when the dragon saw that he had been thrown down to the earth, he pursued the woman who had given birth to the male child. But the woman was given the two wings of the great eagle so that she might fly from the serpent into the wilderness, to the place where she is to be nourished for a time, and times, and half a time.

The Assumption of the Virgin (1530), by Correggio, painted on the interior of the magnificent dome of the Cathedral of Parma. (See detail at WikiPaintings.org)

It is clear even to Protestant interpreters that the male child is Christ Himself. All agree that the symbolism of the Revelation is taking place on several levels and layers: but if the Fathers are correct in their reading of Mary as the ark of Christ’s covenant, then certainly the juxtaposition of that ark, seen within God’s temple, with the mother clothed with the sun giving birth to the Christ is meaningful here.

Blessed Pope John Paul II, of happy memory, taught that in John 14:3, Mary is the fulfillment of Christ’s promise to take us to Him:

And if I go and prepare a place for you, I will come again and will take you to myself, that where I am you may be also.

Saint Paul wrote in 1 Corinthians 15:20-28:

But in fact Christ has been raised from the dead, the firstfruits of those who have fallen asleep. For as by a man came death, by a man has come also the resurrection of the dead. For as in Adam all die, so also in Christ shall all be made alive. But each in his own order: Christ the firstfruits, then at his coming those who belong to Christ. Then comes the end, when he delivers the kingdom to God the Father after destroying every rule and every authority and power. For he must reign until he has put all his enemies under his feet. The last enemy to be destroyed is death. For “God has put all things in subjection under his feet.” But when it says, “all things are put in subjection,” it is plain that he is excepted who put all things in subjection under him. When all things are subjected to him, then the Son himself will also be subjected to him who put all things in subjection under him, that God may be all in all.

If Mary was the firstfruits of Christ’s salvific grace and redemption, then we believe she was also the firstfruits of His resurrection. God did it “out of order” with Mary: He redeemed her from the moment of her conception; so it follows that He would bring about the rest of her salvation out of order, too. He brought her to Him, before the rest of us, as our promise of what awaits us all — to be our beacon of hope and our most gracious advocate on this side of humanity.

In the Fathers

Aside from apocryphal texts, the earliest Church Father to speak to the Assumption of Mary is St. Epiphanius of Salamis (d. 403). He does not mention the Assumption explicitly, but the fact that he raises the matter of Mary’s earthly end attests that there was some question:

The Assumption of the Virgin (1594), by Tintoretto. (WikiPaintings.org)

If anyone holds that we are mistaken, let him simply follow the indications of Scripture, in which is found no mention of Mary’s death, whether she died or did not die, whether she was buried or was not buried. For when John was sent on his voyage to Asia, no one says that he had the holy Virgin with him as a companion. Scripture simply is silent, because of the greatness of the prodigy, in order not to strike the mind of man with excessive wonder.

As far as I am concerned, I dare not speak out, but I maintain a meditative silence. For you would find (in Scripture) hardly any news about this holy and blessed woman, of whom nothing is said concerning her death.

Simeon says of her: “And a sword shall pierce your soul, so that thoughts of many hearts may be laid bare” (Luke 2:35). But elsewhere, in the Apocalypse of John, we read that the dragon hurled himself at the woman who had given birth to a male child; but the wings of an eagle were given to the woman, and she flew into the desert, where the dragon could not reach her (Revelation 12:13-14). This could have happened in Mary’s case.

But I dare not affirm this with absolute certainty, nor do I say that she remained untouched by death, nor can I confirm whether she died. The Scriptures, which are above human reason, left this question uncertain, out of respect for this honored and admirable vessel, so that no one could suspect her of carnal baseness. We do not know if she died or if she was buried; however, she did not ever have carnal relations. Let this never be said!

. . . If the holy Virgin is dead and has been buried, surely her dormition happened with great honor; her end was most pure and crowned with virginity. If she was slain, according to what is written: “A sword shall pierce your soul,” then she obtained glory together with the martyrs, and her holy body, from which light shone forth for all the world, dwells among those who enjoy the repose of the blessed. Or she continued to live. For, to God, it is not impossible to do whatever he wills; on the other hand, no one knows exactly what her end was. (Epiphanius of Salamis, Panarion [Adverus haereses], LXXVIII.11, 23 [PG XLII, 716 B–C, 737])

The first concrete testimony we have in the West to Mary’s Assumption is St. Gregory of Tours (c. 538–594), who cites an apocryphal Greek text, handed down to him in a fifth-century Latin translation, now lost:

Assumption (fragment) (1311), by Duccio. (WikiPaintings.org)

Finally, when blessed Mary, having completed the course of her earthly life, was about to be called from this world, all the apostles, coming from their different regions, gathered together in her house. When they heard that she was about to be taken up out of the world, they kept watch together with her.

And behold, the Lord Jesus came with his angels and, taking her soul, handed it over to the archangel Michael and withdrew. At dawn, the apostles lifted up her body on a pallet, laid it in a tomb, and kept watch over it, awaiting the coming of the Lord. And behold, again the Lord presented himself to them and ordered that her holy body be taken and carried up to heaven. There she is now, joined once more to her soul; she exults with the elect, rejoicing in the eternal blessings that will have no end. (Gregory of Tours, Libri miraculorum I, De gloria beatorum martyrum IV [PL LXXI, 708])

Finally, to see the full flowering of the tradition of the Assumption, we turn to St. John Damascene (d. 749):

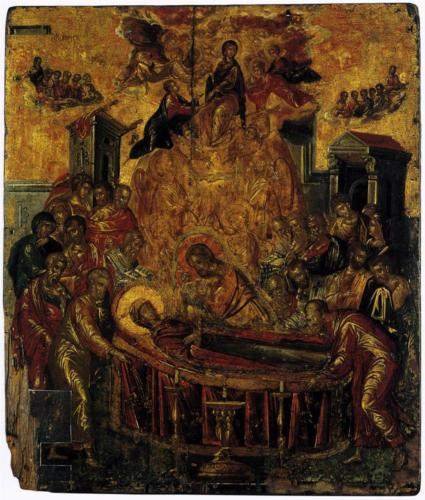

Dormition of the Virgin (1566), by El Greco. (WikiPaintings.org)

Your holy and all-virginal body was consigned to a holy tomb, while the angels went before it, accompanied it, and followed it; for what would they not do to serve the Mother of their Lord?

Meanwhile, the apostles and the whole assembly of the Church sang divine hymns and struck the lyre of the Spirit: “We shall be filled with the blessings of your house; your temple is holy; wondrous in justice” (Psalm 65:4). And again: “The Most High has sanctified his dwelling” (Psalm 46.5); “God’s mountain, rich mountain, the mountain in which God has been pleased to dwell” (Psalm 68:16-17).

The assembly of apostles carried you, the Lord God’s true Ark, as once the priests carried the symbolic ark, on their shoulders. They laid you in the tomb, through which, as if through the Jordan, they will conduct you to the promised land, that is to say, the Jerusalem above, mother of all the faithful, whose architect and builder is God. Your soul did not descend to Hades, neither did your flesh see corruption. Your virginal and uncontaminated body was not abandoned in the earth, but you are transferred into the royal dwelling of heaven, you, the Queen, the sovereign, the Lady, God’s Mother, the true God-bearer [Theotokos].

O, how did heaven receive her, who surpasses the wideness of the heavens? How is it possible that the tomb should contain the dwelling place of God? And yet it received and held it. For she was not wider than heaven in her bodily dimensions; indeed, how could a body three cubits long, which is always growing thinner, be compared with the breadth and length of the sky? Rather it is through grace that she surpassed the limits of every height and depth. The Divinity does not admit of comparison.

O holy tomb, awesome, venerable, and adorable! Even now the angels continue to venerate you, standing by with great respect and fear, while the devils shrink in horror. With faith, men make haste to render you honor, to adore you, to salute you with their eyes, with their lips, and with the affliction of their souls, in order to obtain an abundance of blessings.

A precious ointment, when it is poured out upon the garments or in any place and then taken away, leaves traces of its fragrance even after evaporating. In the same way your body, holy and perfect, impregnated with divine perfume and abundant spring of grace, this body which had been laid in the tomb, when it was taken out and transferred to a better and more elevated place, did not leave the tomb bereft of honor but left behind a divine fragrance and grace, making it a wellspring of healing and a source of every blessing for those who approach it with faith. (John Damascene, Homily 1 on the Dormition 12–13 [PG XCVI, 717D–720C]).

I think it’s telling that for all the thousands of apostolic relics churches around the world claim to have, no one claims to have any piece of body of the Virgin Mary. These beautiful reflections bring me to love my Holy Mother and cherish her Assumption ever more.

[Patristic texts from Luigi Gambero, Mary and the Fathers of the Church (San Francisco: Ignatius, 1991).]