One of the biggest questions in my Catholic journey has been this: How does God view the Catholic and Orthodox and Protestant churches, and their schism with one another? God desires unity in His Church. St. Paul writes to us, “I appeal to you, brothers, by the name of our Lord Jesus Christ, that all of you agree, and that there be no divisions among you, but that you be united in the same mind and the same judgment” (1 Corinthians 1:10 ESV). The very fact of our disunity attests to our sinfulness: We have all fallen short. We have all failed to preserve the unity of His Church. We all share part in the blame — even those of us alive today, we who perpetuate the division and fail to ardently seek reunification.

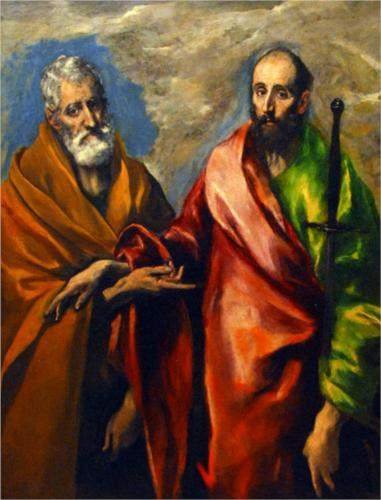

I’ve come to believe, in my journey, that the Catholic Church holds the treasury of apostolic faith, the fullness of truth having been passed down; that it is the One (unus, single, undivided) Holy and Apostolic Church founded by Christ and the Apostles. Studying the history of the Church, I have come to see that the traditions of the Church are not accretions or inventions as I once thought, but have persisted through the great men of faith of the Middle Ages, through the great Church Fathers, all the way since the beginning, the faith of the Apostles. I believe that the Catholic Church represents an unbroken continuity of belief and tradition, from the Apostles to the present day.

Unbroken, that is, except for those who have broken away.* Being raised a Protestant, I always admired and celebrated the great Protestant Reformers. I still do — they were courageous men passionate about God and willing to stand up for what they believed. I cannot, even as a Catholic, paint the Reformers or the Reformation black. The Catholic Church certainly needed to be reformed in many ways — and in fighting back against that reform, she must share a part of the blame for the schism that ensued. I now consider that schism one of the most heart-wrenching and tragic events in all of history — the rending of Christ’s Holy Church, his Spotless Bride.

(* I am not abandoning Eastern Orthodoxy, either. I am only leaving it out of this discussion for simplicity’s sake, because the majority of us Christians in the West are Catholic or Protestant, and because I know comparatively little about the Orthodox churches.)

Protestant churches have borne much good fruit. Christ continues to be active in them, in teaching, love, service, and salvation. There have been many great Protestant thinkers and theologians — and I do consider their thought and theology great; they are worthy and useful ways for thinking about God and our life in Him. There have been many good and holy Protestant servants of Christ, who have fed the hungry, clothed the poor, bound up the wounds of the hurting, and won many souls for His kingdom. God, without a doubt, uses, ministers, and saves through Protestant churches.

So God is merciful and forgives us of our sins — even the great sin of breaking His Church into fragments. But is that enough? Is it enough to accept His forgiveness, accept the fact of our division as final and irrevocable — that what’s been done is done, and we can’t go back? That this is the way things are now? That our churches can’t break bread together, and that’s okay? To most Protestants (to me as well, not that long ago), the thought of rejoining with the Catholic Church is unthinkable. To many, it is outright offensive. To them, the Catholic Church had sinned and been corrupted; it needed to be re-created. But even supposing that were true — the fact remains that the Christian Church — the Body of Christ — is fragmented. Are we going to allow this to persist?

There have many efforts over the years at ecumenism. Mostly in recent times, this has consisted of getting some members of the various churches together to share and discuss what they have in common and worship together. I applaud this, and think there needs to be more of it: the more we all talk to each other, the more we’ll realize that we all share the same Christ, and that He doesn’t want us to be divided. Others, however, continue to attack our differences, and decry any ecumenical efforts. How can this be what Christ wants? Can any of these people really sit down with faithful Catholics and continue to believe that Catholics are not Christians? How can anyone believe that our God is so small as to exclude large bodies of believers from His Kingdom because of minor doctrinal differences?

I feel that the onus is on us to seek not just dialogue, but reunification of Christ’s Church. As we ever approach the end of the age, we will need each other — we will need to be One and whole as a faith — more than ever. Recognizing this need for reunion is one of the many reasons for my decision to join the Catholic Church. History has failed to prove to me that the Catholic Church has ever been “wrong” or “corrupt” to the point of justifying a break (everyone sins; but she has never departed from the Truth); and so, if she was not “wrong,” then she must still be “right.” And the onus is on me to do what I can to make reparation for my ancestors' mistakes (this probably applies to my ancestors other mistakes as well). I am just one lonely pilgrim, but in returning to Rome, I am doing what I can. And I am a part of an ever-growing wave. And I believe as this wave gains momentum, it will sweep up more than only individuals. I truly have hope to see whole churches, even whole denominations, return to communion with Rome. I truly have hope to see, in my lifetime, a reunification of all Christians.

Just as the blame for our division is shared among all Christians, I believe that in reunification, some ground must be given by all. I’m not an expert on this — more learned people than I have written whole books on the problem of reunification — but the baseline for communion with Rome would have to be, I think, accepting the authority of the Pope and Magisterium, and belief in the Sacraments. I think the idea of accepting an institutional church authority at all will be most difficult for many Protestants — but I’ve come to see that it’s necessary. From Rome’s position, I think there is plenty of ground to yield regarding practice: just as Rome is embracing many Anglicans and allowing them to preserve their Anglican identity and heritage, and just as the Eastern Catholic Churches are embraced in all their differences, even a “Baptist rite” or a “Presbyterian rite” could be accommodated. I can quite easily imagine the liturgy of a Baptist church that embraced Rome and the Sacraments, while still remaining essentially Baptist.

We are all Christians, after all. We all worship the same Triune God. We all believe the same things about Christ. We all adhere to the same creeds†, whether we proclaim them or not. Regarding the Sacraments, our differences of opinion are more minor than most people recognize. Unity is within reach — if only we are willing to reach out. The onus is on every one of us.

† Obviously, I am excluding those who don’t — Sorry. Y’all come on back now, too.