This should be the conclusion of my three-parter on the Tomb of St. Peter at St. Peter’s Basilica on the Vatican, in which I hope to discuss the discovery of St. Peter’s relics and the issue of their authenticity. Also, a bibliography! Previously, “The Tomb of St. Peter,” “The Grave of St. Peter.“

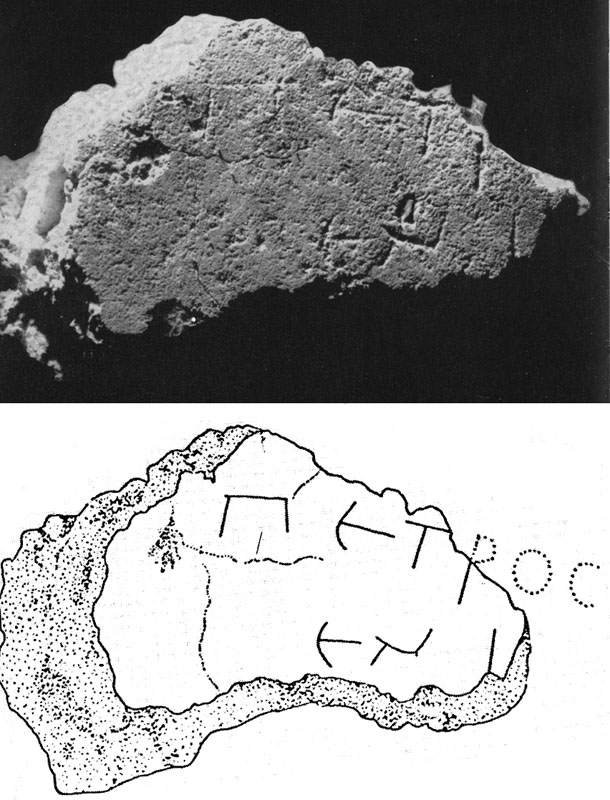

The bones found beneath the Red Wall (briefly replaced there for the photograph). (Fabbrica di San Pietro)

The bones the Vatican archaeologists had discovered in 1942, in the niche at the foundation of the Red Wall, to one side of St. Peter’s grave, remained safely locked in lead-lined chests in the private chambers of the pope for over a decade. Only a cursory examination had been given to them by the pope’s private physician, who declared that they were the bones of a man in his seventies — the age Peter was expected to have been at his martyrdom. The pope had made only a brief, uncertain announcement concerning the bones in 1950. The hungry press, a curious academia, and the anxious Church widely wondered about their authenticity, and the frustration only built at the Vatican’s reticence and characteristic slowness.

Finally, in 1956, at the request of Pope Pius XII, Venerando Correnti, a leading anthropologist and professor at Palermo University, examined the Red Wall bones. Correnti’s meticulous examination and testing took over four years. In the end, his findings were disappointing: these were almost certainly not the bones of Peter. The pile contained the bones of as many as four individuals: two men in their fifties, a man in his forties, and an elderly woman in her seventies, as well as an assortment of animal bones. The animal bones were not a great surprise: the ancient necropolis was known to have been near the emperor Nero’s circus and stables, and discarded animal carcasses may have left their bones strewn all throughout the area.

The bones that had been the objects of hope for over a decade — the bones found in, or at least to the side of, St. Peter’s grave — were not the saint’s relics at all. But that is not the end of the story. Another set of bones had been discovered at the site, that Correnti now prepared to examine.

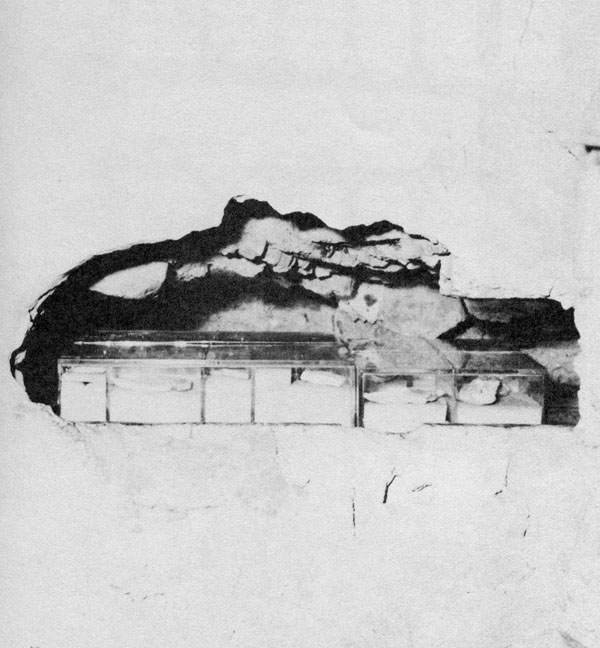

The Graffiti Wall, on the north side of the Tropaion, showing the repository. (Fabbrica di San Pietro)

Unknown to the archaeologists at the time, there had been a serious blunder early in the excavation. Early in 1942, when the team had first discovered the Graffiti Wall at the north side of the Tropaion, with its curious marble receptacle slightly exposed, they had initially chosen not to disturb it, wishing to fully photograph and document the valuable graffiti before risking damage to the plaster by reaching into the hole. When they finally did examine it, they found nothing inside but a medieval coin, some bone fragments, and other debris.

But by the time they got to it, the receptacle had already been tampered with. Monsignor Ludwig Kaas, the administrator of St. Peter’s Basilica and nominal head of the investigation, had a habit of inspecting the excavations alone at night after the archaeologists had left. Kaas was not an archaeologist himself, and had little appreciation for proper archaeological procedure. Troubled by possible disrespect to the bones of saints, as unknown graves and bones were uncovered in the course of the investigation and set aside, Kaas would remove these bones and place them respectfully in boxes.

In this diagram of the Niche of the Pallia and the surrounding tomb, the Graffiti Wall is labeled Wall g. (Fabbrica di San Pietro)

Late one night within a couple of days of the Graffiti Wall being exposed, Kaas examined it and its receptacle. He brought with him Giovanni Segoni, one of the foreman of the Sampietrini, the skilled workmen charged with the care of St. Peter’s Basilica, who had been assisting in the excavations. At Kaas’s direction, Segoni widened the hole in the plaster and removed the contents of the repository: a considerable pile of human bones with some shreds of reddish cloth. Segoni placed these in a wooden box, sealed it, and labeled it. The box would remain in a storeroom throughout the remainder of the excavation, unknown to any of the archaeologists.

In 1952, when Dr. Margherita Guarducci was examining the graffiti of the Graffiti Wall, she encountered Segoni by chance. She inquired about the contents of the receptacle and learned that he had emptied it himself, and he led her to the box. Not realizing that the archaeologists were unaware of Kaas’s actions, Guarducci was surprised by the size and extent of the bones, and even more so by what she believed was a failure on the part of the archaeologists to document them and consider their importance. It was not until more than a decade later, when Guarducci discussed the matter with Kirschbaum and the other archaeologists, that all realized what had happened.

But Guarducci placed the neglected bones in the queue for Correnti to examine. Preoccupied for so long with the disarrayed pile of Red Wall bones, Correnti did not get to the Graffiti Wall bones until 1962. Fully expecting this to be another collection of mixed bones, he was surprised by his unexpected findings: they were the remains of one elderly man, between sixty and seventy years old, of sturdy build. There were two other puzzling aspects: the bones were encrusted with soil in their crevices and hollows, as if buried and exhumed; and a number of the larger bones appeared to have been stained with a reddish or purplish dye, the color of the shreds of fabric discovered in the box. Sometime after the decay of the flesh, the bones had been dug up from a grave and wrapped in a purplish cloth.

The inside of the Graffiti Wall repository. (Fabbrica di San Pietro)

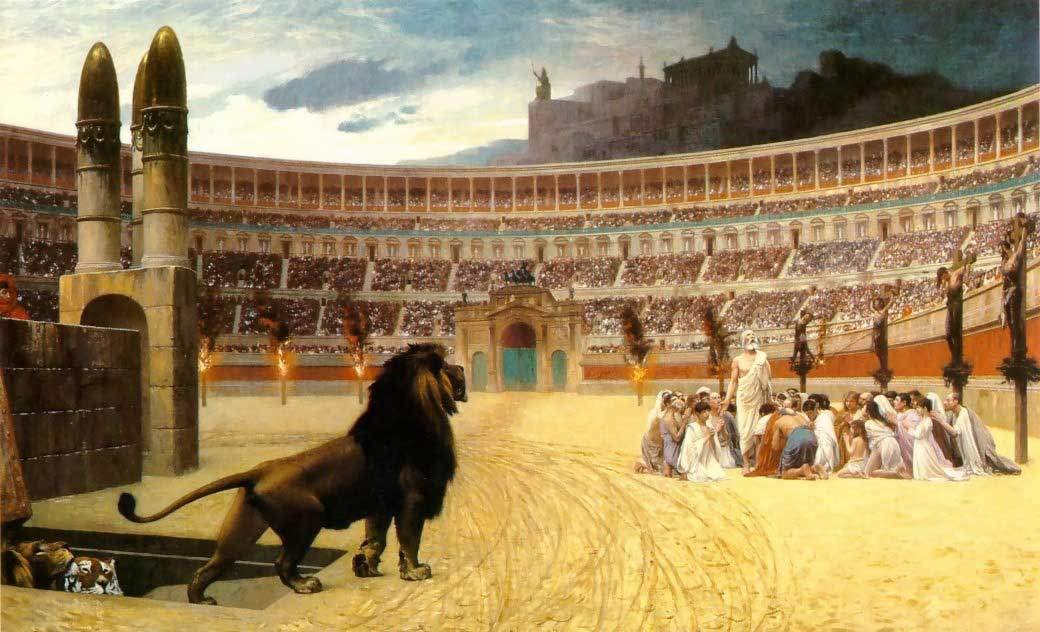

It was Guarducci who, learning of Correnti’s findings, developed the theory that the Graffiti Wall bones might be the bones of St. Peter himself. But why would Peter’s bones be in the marble repository of the Graffiti Wall, and not in the central grave? What was the purpose of the repository? It might have been, Guarducci reasoned, a hiding place, a container for the bones’ safekeeping and protection from Roman persecutors and vandals. At the time of the Graffiti Wall’s construction in the mid-third century, Christianity was under the most aggressive persecution it had suffered in decades, under the emperors Decius and Valerian. Might the Church have felt the bones were threatened?

A closer examination of the scraps of cloth discovered with the bones brought a stunning revelation: it was a cloth dyed what appeared to be purple, and interwoven with pure gold thread of the finest craftsmanship. The dye used, upon chemical testing, proved to be the authentic Roman purpling agent, reserved for royalty.

A sampling of the bones believed to be those of St. Peter. These are the carpals and metacarpals of the left hand. (Fabbrica di San Pietro)

And the dirt encrusted on the bones — could it reveal where the bones had been before? Testing the soil composition of the central grave, the outer courtyard, and the area around the Graffiti Wall, the soil on the bones was a perfect match for the soil in the central grave, quite distinct from the soil in the other locations. These bones appeared to have been at one time buried in the central grave.

But hadn’t the repository been opened in the Middle Ages, as evidenced by the medieval coin discovered inside? A careful disassembly of the Graffiti Wall by the archaeologists revealed that the receptacle had in fact been intact since its construction, and was only cracked open by the archaeologists’ recent excavations (with sledgehammers). While taking it apart, a number of other coins fell out from the wall’s crevices; they reasoned that the medieval coin had fallen into the repository through these cracks. The remains of a dead mouse were also discovered inside, who must have entered somehow — verifying the possibility that small items might have entered the repository without breaching it.

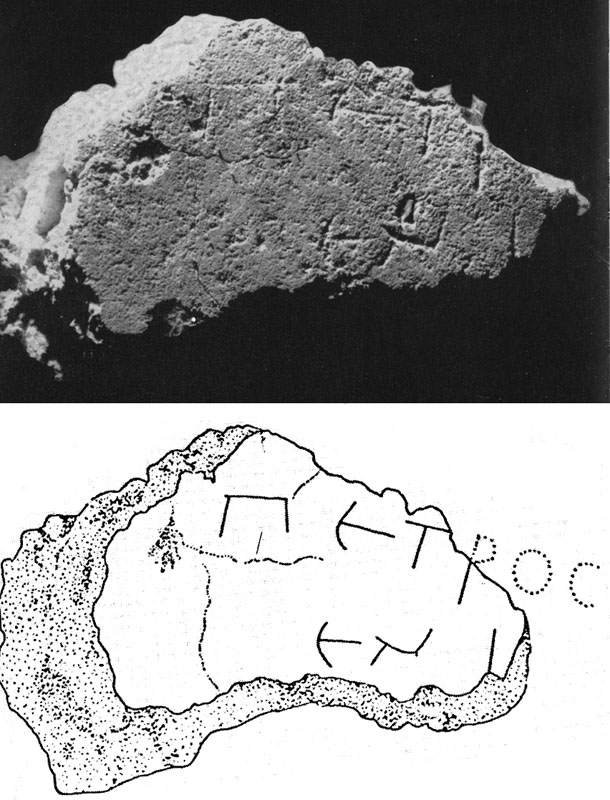

The Petros Fragment from the Red Wall, discovered inside the repository. (Fabbrica di San Pietro)

Another fact that had been overlooked, seemingly irrelevant when the repository was thought to have been empty: the fragment of the Red Wall bearing the “Petros eni” (“Peter is inside”) inscription had been discovered inside the repository, jarred loose from a position on the Red Wall where the Graffiti Wall met it and covered it. Perhaps the placement of the inscription was related to the repository. Perhaps, in fact, the words had been hastily scratched just as the wall was being sealed with the bones inside.

The reliquaries in the ciborium of St. John Lateran, of the heads of St. Peter (right) and St. Paul (left).

And what of the other relics held by the Church to belong to St. Peter? The Basilica of St. John Lateran holds in its reliquaries what are believed to be the heads of Peter and Paul. The last time the Lateran reliquaries had been opened was 1804, when it was observed that only fragments remained of the heads. At least one fragment of a skull had been found with the Graffiti Wall bones — would this conflict with the remains of the Lateran skull? With the permission of Pope Paul VI, the Lateran reliquary was opened and Correnti was allowed to examine its contents. The one condition was that he could not report detailed information about the Lateran relic, for the sake of its veneration; he could only state whether or not it in any way conflicted with or contradicted the Graffiti Wall bones. After several months of careful study, Correnti announced unequivocally that the two sets of bones were consistent with each other.

The supposed relics of St. Peter returned to their repository in the Graffiti Wall. (Fabbrica di San Pietro)

On June 26, 1968, Pope Paul announced to the world that the relics of St. Peter had been discovered and identified. Not every question had been answered, but the pope himself was convinced. When all examinations were complete, the researchers carefully placed the bones in nineteen clear, padded plastic containers, and with a brief ceremony, returned them to their resting place in marble repository of the Graffiti Wall.

My feelings about whether these Graffiti Wall bones are the true relics of St. Peter have been wavering back and forth. Some points for consideration:

- This is almost certainly St. Peter’s grave (see my reasoning). At the time the Church turned the tomb over to Constantine, its leaders clearly believed the grave was intact and the relics still there, as did Constantine himself. But why weren’t these bones in the grave itself? If the Graffiti Wall bones are Peter’s, did the leaders of the fourth century Church remember they were there?

- The Graffiti Wall repository was built for a reason, and apparently built to be hidden. If not a hiding place for Peter’s bones, then whose? Other people had been buried close to Peter — but who else might have warranted a burial in Peter’s Tropaion itself?

- Following the decay of the flesh from these bones, the bones had been exhumed from the earth, as evidenced by the earth encrusted on them. They were then wrapped with a purple cloth, as shown by the dye stains on the bones themselves. Clearly these bones were transferred from their original grave and placed in the wall repository. And the earth on the bones is consistent with the earth of the central grave.

- The cloth that wrapped the bones was sumptuous, of the richest royal purple and interwoven with delicate gold thread. It is doubtless these bones belonged to a greatly venerated individual.

- The Graffiti Wall and its repository are believed to have been constructed in the mid-third century, probably the decade between 250 and 260. The repository was then sealed, and not exposed until the excavations of the 1940s. So these bones must belong to someone who died in the first three centuries. No carbon dating was performed on the bones out of a reluctance to destroy any piece of the relics, and a decision that it would not reveal any more precise date than could be reckoned by the above logic.

- The “Petros eni” fragment was in the section of the Red Wall that was covered up by the Graffiti Wall and its repository. Could the marking refer to the resository — Peter is inside here? Was it marked as the wall was being sealed?

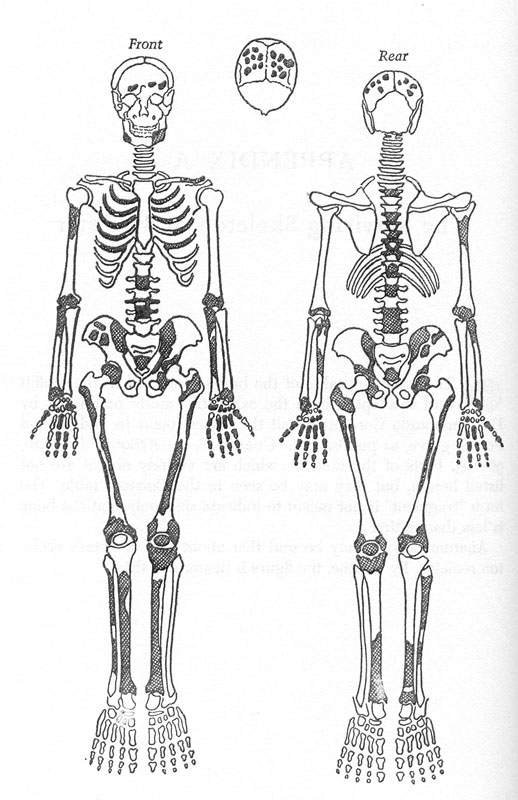

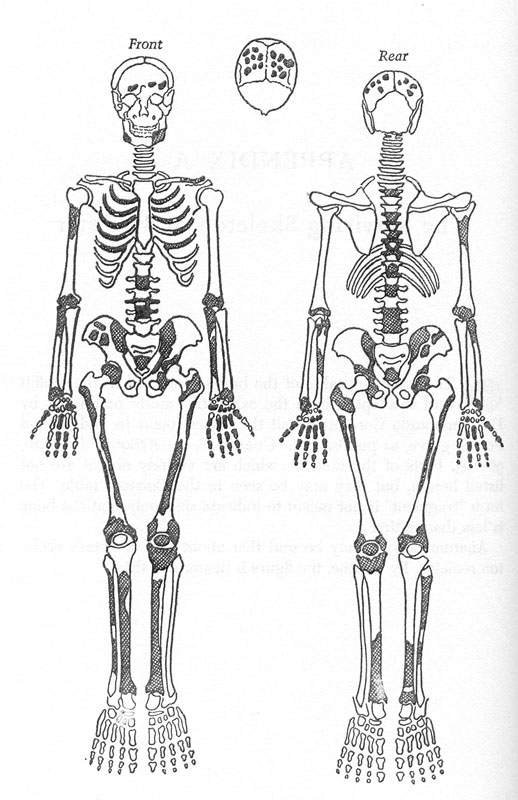

The surviving parts (shaded) of the skeleton believed to be St. Peter’s. Anatomically, about one half of the skeleton survives; by volume, about one third. (Walsh)

- The bones belong to an elderly male, probably between the ages of sixty and seventy, of a sturdy build. This is consistent with the facts known of St. Peter, who is believed to have been martyred between 63 and 67.

- The surviving skeleton, including a fragment of the skull and jawbone, were deemed not to conflict in any way with the skull and jaw fragments believed to reside in the Lateran reliquary.

- Also very curiously, every part of the skeleton is represented by the bones but the feet, which are both absent in their entirety. Conceivably this could be a product of Peter having been crucified upside down: for an easy and hasty removal from the cross, the body might have been hacked off above the ankle.

- At the time Constantine built his memoria encasing the tomb and St. Peter’s Basilica around it, he chose to preserve it exactly as it was, including the asymmetrical and unaesthetic Graffiti Wall, which forced the memoria to be slightly lopsided in shape (and the Niche of the Pallia continues to be to this day). Why was this part of the monument kept despite its unattractiveness? Did the Church insist on its retention, knowing it contained the relics?

At the moment, I’m leaning toward these bones being the genuine relics of St. Peter. This certainly isn’t a conclusive case. It, like so much, has to be a matter of faith for the faithful — and it’s certainly not an essential point of faith for anyone. I am reassured by the thought that this is certainly the grave of Peter, in which his earthly body decayed, and in which his dust lies, whether these are his bones or not. The magnificent church of St. Peter’s Basilica, the central church of Roman Catholic Christianity, if not all of Christendom, stands over the grave of the Prince of Apostles.

Bibliography

Books

- Walsh, John Evangelist. The Bones of St. Peter. New York: Doubleday, 1982. The first book I read on the subject. A riveting and detailed narrative and great introduction to the excavations and to the question of Peter’s bones, and the most up-to-date publication. Full text available online (but missing many of the helpful diagrams, I think).

- Kirschbaum, Engelbert, S.J. The Tombs of St. Peter and St. Paul. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1959. A more detailed and technical account of the excavations by one of the leading excavators himself. More satisfying and informative from a technical standpoint than Walsh, which helped me in some questions I still had in visualizing the excavation.

- Toynbee, Jocelyn, and John Ward Perkins. The Shrine of St. Peter, and the Vatican Excavations. New York: Pantheon, 1957. I’ve just started reading this one. But Toynbee and Ward Perkins are two very well-known names in both history and archaeology, and this book is frequently referenced in the other two books. I understand that they, as outsiders, had a more critical approach to the excavations.

- Margherita Guarducci. The Tomb of St Peter. Hawthorn Books, 1960. I haven’t read this one yet, but I look forward to Guarducci’s account. It’s also available online.

Websites

There are extensive bibliographies to additional books, articles, and other publications in the books, especially Walsh. In fact, here you go. That should lead you to most everything that’s out there — though it’s possible there have been publications since 1982.