Why is it that it’s only when I have a dozen other things I’m supposed to be doing (cleaning my disgusting apartment, doing laundry, revising a history paper for school) that my mind is bursting with blog ideas?

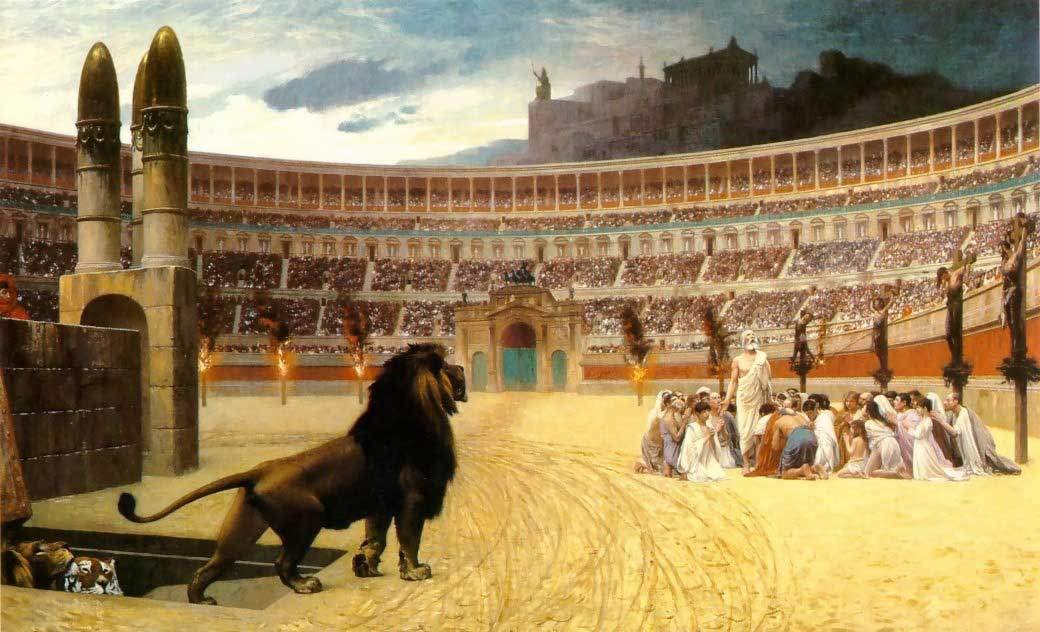

The Christian Martyrs’ Last Prayer (1883), by Jean-Léon Gérôme, my favorite Orientalist painter. It truly captures the drama and the agony of the first Christian persecutions, and yet the peace before God.

Today is the Feast of the First Holy Martyrs of the Holy Roman Church, celebrated the day after the Feast of Saints Peter and Paul. This celebration encompasses the many nameless Christian martyrs who suffered under the persecution of the emperor Nero beginning in A.D. 64 (Peter and Paul both also died under this persecution), as well as many other lesser-known Roman martyrs.

These persecutions are vividly described in the Annales (Annals) of the Roman historian Tacitus (A.D. 56–117), one of the first mentions of Christianity in secular literature, written ca. A.D. 116. The context is the aftermath of the Great Fire of Rome in July 64 (Annales XV. 44, ed. G. P. Goold, trans. John Jackson, for Loeb Classical Library, 1937):

But neither human help, nor imperial munificence, nor all the modes of placating Heaven, could stifle scandal or dispel the belief that the fire had taken place by [Nero’s] order. Therefore, to scotch the rumour, Nero substituted as culprits, and punished with the utmost refinements of cruelty, a class of men, loathed for their vices, whom the crowd styled Christians. Christus, the founder of the name, had undergone the death penalty in the reign of Tiberius, by sentence of the procurator Pontius Pilatus, and the pernicious superstition was checked for a moment, only to break out once more, not merely in Judaea, the home of the disease, but in the capital itself, where all things horrible or shameful in the world collect and find a vogue. First, then, the confessed members of the sect were arrested; next, on their disclosures, vast numbers were convicted, not so much on the count of arson as for hatred of the human race. And derision accompanied their end: they were covered with wild beasts’ skins and torn to death by dogs; or they were fastened on crosses, and, when daylight failed were burned to serve as lamps by night. Nero had offered his Gardens for the spectacle, and gave an exhibition in his Circus, mixing with the crowd in the habit of a charioteer, or mounted on his car. Hence, in spite of a guilt which had earned the most exemplary punishment, there arose a sentiment or pity, due to the impression that they were being sacrificed not for the welfare of the state but to the ferocity of a single man.