La Última Cena (ca. 1562), by Juan de Juanes. (Wikipedia)

Merry Christmas and Happy New Year to all. Yeah, I’m a little late on that one, but it’s been a busy and stressful few weeks. I’m still trying to settle back in at home, and re-situate my books and my life, and make progress on my thesis.

I’ve been stressing, too, you know, about the next post in my series on the Sacraments: an introductory post on the Eucharist. How can I do such a subject justice in a single brief post, or even in a dozen? It’s had me bound up for weeks, researching fervently and never feeling worthy. So I finally decided to sit down and give you, rather than the ultimate, perfect, authoritative post, a human and personal reflection.

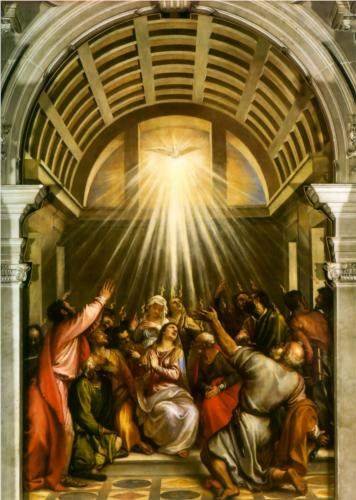

We Catholics say that the Eucharist is “the source and summit of the whole Christian life.” (Second Vatican Council [1964], Lumen Gentium III.11.1, lit. totius vitae christianae fons et culmen — those words are a lot richer than they come across in English: fons is the fount from which the blessings of our faith flow; culmen means the very peak, the summit, the apex, the culmination). As a Protestant growing up, I had no notion of this — we rarely celebrated Holy Communion in the churches I was a part of — and even early in my conversion, after I’d begun attending Mass, I couldn’t comprehend it. I used to think as a Protestant that the Real Presence of Christ in the Eucharist was merely a pious superstition, one inconsequential to the substance of the Christian faith and message: what does it matter whether He’s really there or not, as long as we believe in Him and follow Him? What is the big deal about the Lord’s Supper? Why make Communion the central act of the Christian life — the very reason for going to church? Don’t we have better things to focus on, like edification through preaching and teaching, and fellowship and support through community, and ministry to the lost and hurting? As I heard Mass, as I witnessed it and stood in the presence of the Eucharist, though unable to partake, a glimmer of the truth began to dawn on me; but it wasn’t until the very moment of my First Communion, the first time I came to the Eucharistic table and experienced it for myself, that the full reality, the full mystery, hit me and overwhelmed me.

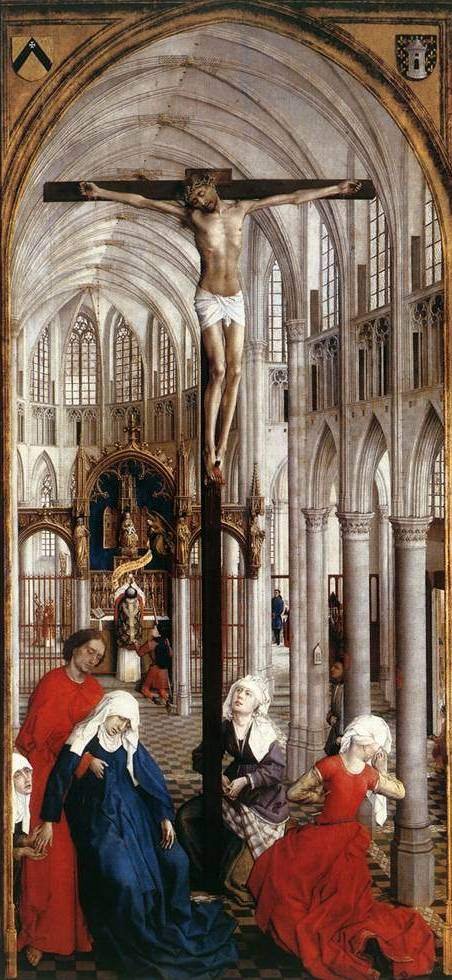

Seven Sacraments Altarpiece (1450), by Rogier van der Weyden. The center panel, showing the Eucharist, the source and summit of our faith.

The Eucharist is the source and summit of the whole Christian life because it is Christian life itself. In the Eucharist we have the very Body and Blood, Soul and Divinity of Jesus Christ, really and truly present. In Holy Communion we share in His full humanity and His full divinity; we partake of His eternal life itself — the love and the life of God delivered to us directly, not just spiritually but corporeally and viscerally. We are united with Him more intimately than we can ever be united with anyone else, in the flesh as well as in the spirit; united with the very Body of Christ, in Communion not only with Him but with all the saints and believers who have been united with Him over the ages, in the Church on earth and in His eternal kingdom. The Eucharist is our font and our apex because from it flows all else: all the grace by which God forgives us and saves us; all the faith and hope and love with which He imbues us; all the power and authority and ability He gives us to turn from sin and follow Him, to pursue His righteousness, to love and minister to others. All the preaching, all the teaching, all the ministry, all the fellowship are subsumed to the Eucharist because without the Eucharist we could have none of those. It is the source of our life; our very food from heaven.

In the grace of the Eucharist, I find so much strength, but at the same time see how truly weak I am, how desperately I need Christ, how I am nothing without Him. Where before the Lord’s Supper was “no big deal” to me, a nice symbol and memorial, now not only my faith, but my entire life orbits the Eucharist. I know I cannot live without His Presence; the Lord’s Day is the center of my week; my soul and my body ache to be departed from Him even the few days in between. What is this miracle, what is this mystery, what is this treasure God has given us?

The Protestant will ask, can you support that biblically? And yes, Jesus states it plainly (John 6:22–71):

I am the bread of life; whoever comes to me shall not hunger, and whoever believes in me shall never thirst. … I am the bread of life. Your fathers ate the manna in the wilderness, and they died. This is the bread that comes down from heaven, so that one may eat of it and not die. I am the living bread that came down from heaven. If anyone eats of this bread, he will live forever. And the bread that I will give for the life of the world is my flesh.”

“Truly, truly, I say to you, unless you eat the flesh of the Son of Man and drink his blood, you have no life in you. Whoever feeds on my flesh and drinks my blood has eternal life, and I will raise him up on the last day. For my flesh is true food, and my blood is true drink. Whoever feeds on my flesh and drinks my blood abides in me, and I in him. As the living Father sent me, and I live because of the Father, so whoever feeds on me, he also will live because of me. This is the bread that came down from heaven, not like the bread the fathers ate, and died. Whoever feeds on this bread will live forever.

Whoever feeds on my flesh and drinks my blood abides in me, and I in him. Somehow, by some tragic blindness, Protestants interpret this passage as symbolism and metaphor. But the universal witness of the early Church attests to the belief of the earliest Christians in the Real Presence of Christ in the Eucharist, and of its centrality to the Christian life. For Christian life is about communion with Christ — even Protestants should admit this — and it is only in the Eucharist, the Most Blessed Sacrament, that we have the true and full Communion with Him that His Body was broken for; that He gave to us for all time.