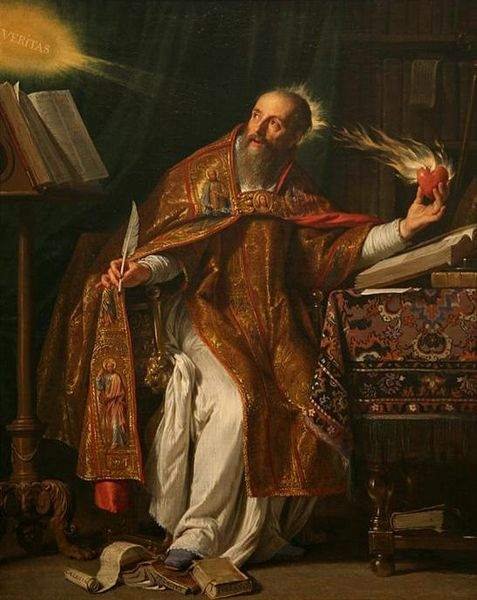

Apostle St. Paul (c. 1612), by El Greco.

One of the most iconic phrases of the English New Testament, one of the Apostle Paul’s great quotes that has always echoed in my ears growing up, is to “work out your own salvation with fear and trembling” (Philippians 2:12). But what does that even mean?

Therefore, my beloved, as you have always obeyed, so now, not only as in my presence but much more in my absence, work out your own salvation with fear and trembling, for it is God who works in you, both to will and to work for his good pleasure.

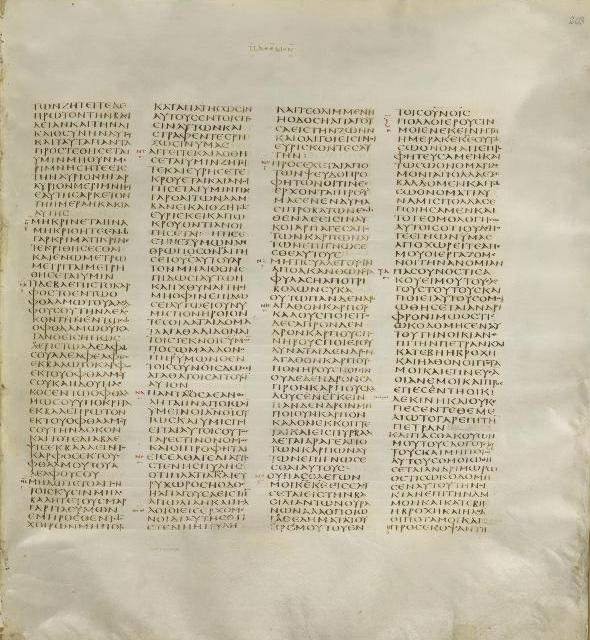

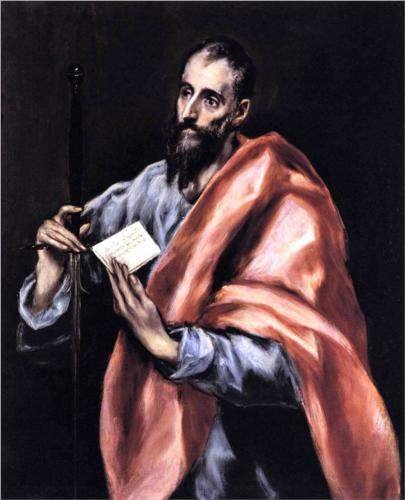

A leaf from Codex Sinaiticus, the oldest known Greek uncial manuscript of the entire Bible (c. A.D. 330–360).

As a Protestant, I admit I never thought much about it. I guess I had a vague sense of “working something out” with God, the way one negotiates an agreement or a solution — through a process of trial and error, learning and growing as a Christian, to reach a situation that “worked.” If the verse meant anything to me, it was as an encouraging exhortation: Keep on obeying God, and you and God will “work it out.”

As I’ve been growing as a Catholic, this verse has been an indication that there might be some “work” involved in salvation in Paul’s view, as opposed to the sola fide (by faith alone) interpretation that the Protestant Reformers so ardently expressed. It’s been a handy crutch in presenting the Catholic position. “But, Paul said ‘work out your own salvation’!”

But what did Paul really mean? Recently I decided to delve into the Greek in order to explore this. What I found was a little startling.

Here is the Greek (only the bolded portion from above; Greek text from NA27):

. . . μετὰ φόβου καὶ τρόμου τὴν ἑαυτῶν σωτηρίαν κατεργάζεσθε· θεὸς γάρ ἐστιν ὁ ἐνεργῶν ἐν ὑμῖν καὶ τὸ θέλειν καὶ τὸ ἐνεργεῖν ὑπὲρ τῆς εὐδοκίας.

Transliterated into Roman characters, for your benefit:

. . . meta phobou kai tromou tēn heautōn sōtērian katergazesthe, theos gar estin ho energōn en humin kai to thelein kai to energein huper tēs eudokias.

And now broken down:

. . . μετὰ [preposition, with, in the midst of] φόβου [fear] καὶ [and] τρόμου [trembling] τὴν [definite article, accusative singular: goes with σωτηρίαν] ἑαυτῶν [3rd person reflexive pronoun, genitive plural: your own] σωτηρίαν [accusative singular (the direct object, being acted upon): salvation] κατεργάζεσθε [present middle deponent, 2nd person plural imperative: (you) “work out”] · θεὸς [God] γάρ [postpositive particle, for] ἐστιν [3rd person active indicative, impersonal, (it) is] ὁ ἐνεργῶν [present active participle, nominative singular: acting, operating, working, being efficacious] ἐν [preposition, in] ὑμῖν [second person plural personal pronoun, you] καὶ [and (together with other καὶ, both . . . and)] τὸ θέλειν [present active infinitive: to be willing, wish] καὶ [and] τὸ ἐνεργεῖν [present active infinitive, same verb as above: to act, operate, work, be efficacious, effect, execute] ὑπὲρ [preposition, for] τῆς εὐδοκίας [genitive singular, (his) good will].

What startled me is that to “work out” is all contained in the verb κατεργάζομαι. “Work out” is a single action, and “salvation” is the direct object — the object on which the action is performed. But salvation isn’t supposed to be something we act on at all, is it?

The BDAG, the most authoritative lexicon of New Testament Greek, gives four definitions for κατεργάζομαι:

- to bring about a result by doing something, achieve, accomplish, do.

- Romans 7:15-20: For what I do, I do not understand; for I do not practice what I prefer, but I do that thing I hate. But if I do the very thing I do not prefer, I agree with the Law, that it is good.

- 1 Corinthians 5:3: . . . I have already pronounced judgment on the one who did such a thing.

- to cause a state or condition, bring about, produce, create.

- Romans 4:15: For the law brings wrath, but where there is no law there is no transgression.

- Romans 5:3 Not only that, but we rejoice in our sufferings, knowing that suffering produces endurance . . .

- to cause to be well prepared, prepare someone.

- to be successful in the face of obstacles, overpower, subdue, conquer.

- Ephesians 6:13: Therefore take up the whole armor of God, that you may be able to withstand in the evil day, and having done [proving victorious over] all, to stand firm.

Of these definitions, the BDAG suggests that the second one, to bring about, produce, create, is the appropriate one for our verse, Philippians 2:12.

The Friberg Analytical Lexicon agrees with the definitions of the BDAG. Similarly, the Louw-Nida Lexicon Based on Semantic Domains suggests that the use of κατεργάζομαι in Philippians 2:12 implies a change of state: “to cause to be, to make to be, to make, to result in, to bring upon, to bring about.” Joseph Henry Thayer's Lexicon (1886; revised 1889), which I still rather like, obsolete though it may be, suggests the Latin efficere for the usage of the word in this verse: “to work out, i.e. to do that from which something results.” St. Jerome's Vulgate translates the word operor, which Lewis and Short defines “To work, produce by working, cause.”

So what does all this mean? It means that “work out” in Philippians 2:12 has a much more active meaning than I formerly supposed. There is agreement between all the lexica I consulted: κατεργάζομαι implies a very strong sense of bringing about, producing a state or condition. The result is that the correct understanding of this verse is that with fear and trembling, we are to bring about, produce, effect our own salvation. This seems startlingly un-Pauline, at least according to the Protestant understanding of Paul’s theology.

William Tyndale, first translator of the Bible from its original languages into English.

But I should remind my Protestant readers that despite how Luther wanted to read Paul, Paul never once says by faith alone. Paul stresses justification by faith in opposition to the Judaizers, who stressed their works and denied that faith had any role, insisting that salvation in Christ came only by the works of the Jewish Law — that being circumcized would in itself bring salvation. Paul denies that works bring salvation; it is faith, the gift of God, that saves us, not the result of our own works. But Paul never denies that works are also important. He in fact writes of the importance of good works: we are “created for good works, which God prepared beforehand, that we should walk in them” (Ephesians 2:8-10). God “will render to each one according to his works: to those who by patience in well-doing seek for glory and honor and immortality, he will give eternal life” (Romans 2:7). The people of God are to devote themselves to good works (Titus 3:8,14).

And now, by obeying Christ, we are to bring about our own salvation — a command, a strong imperative statement in the Greek. And through our working, it is not our own doing or merits that brings this about, but God who works in us by His grace, both to will (wish, want, prefer) to do good, and to work (to be active, effectual, able to bring about). Though at first it appears unlike Paul for him to say that we produce our own salvation, he is here consistent in reminding us that it is not our works that bring about our salvation, but God working in us. This interpretation is consistent in every way with Roman Catholic doctrine.

But in the English — to work out our own salvation — where does this come from? Given this clear, active meaning of κατεργάζομαι, with so strong a sense of working, producing, effecting, why has nearly every major English Bible translation since the sixteenth century — including Catholic ones — translated this phrase “work out your own salvation”?

The title page to Tyndale’s 1534 edition of the New Testament.

I suspected immediately that this was a Tyndalism — a translation first promulgated by William Tyndale in his 1534 English New Testament, that has such a sonorous ring to it, and that, by way of being assumed into the 1611 King James Version (of which Tyndale’s work makes up about 80%), has become so ubiquitous in the English language that no translator dare change it. Examples of the many other Tyndalisms include “Let there be light,” “gave up the ghost,” “my brother’s keeper,” “it came to pass,” and the nearly universal translation of the Our Father or Lord’s Prayer, which even Roman Catholics pronounce according to the King James translation (“And lead us not into temptation, but deliver us from evil”). Tyndale also coined many words that have enriched the English language, including “scapegoat,” “Passover,” and “Jehovah.”

A little bit of research confirmed that I was correct. Stepping through the history of English Bible translation:

Wycliffe Bible (1380s): worche ye with drede and trembling youre heelthe

Tyndale Bible (1534): worke out youre awne saluacion with feare and tremblynge

Coverdale Bible (1535): worke out youre awne saluacion with feare and tremblynge

Matthew Bible (1537): worke out youre awne saluacion with feare and trembling

Great Bible (1539): worke out youre awne saluacion with feare and tremblyng

Geneva Bible (1560): make an end of youre owne saluation with feare and trembling

Bishop’s Bible (1568): worke out your owne saluation with feare and tremblyng

Revised Version (1885): work out your own salvation with fear and trembling

New Intl. Version (1978): continue to work out your salvation with fear and trembling

Now that’s staying power. With only one slight exception — the overly Calvinistic Geneva Bible, which changed “work out” to “make an end of” — every English Bible translation since Tyndale’s own has left Tyndale’s wording and phrasing of this verse intact.

I have intentionally not included Roman Catholic translations in the list above, to demonstrate Tyndale’s overpowering influence:

Even into the Catholic mind, Tyndale’s leaven worked through the whole batch. Despite the Rheims translators’ initial attempt to escape Tyndale’s shadow — self-consciously avoiding translations that would appear to support Reformation theology, and replacing work out with work, though retaining Tyndale’s feare and trembling — Bishop Challoner reverted the whole thing to Tyndale’s wording. It has stuck ever since.

So why “work out” — a phrase with such an ambiguous meaning? Was Tyndale trying to obscure a phrase that seemed to cast doubt on Protestant theological suppositions? No, apparently not. Rather, “work out” has an archaic usage that is no longer current in today’s English. According to the Oxford English Dictionary:

work out. II. 6. To bring about, effect, produce, or procure (a result) by labour or effort; to carry out, accomplish (a plan or purpose).

In fact, this is the very meaning of the Greek word. And according to the OED citations, Tyndale’s is the first use of the phrase in this sense on record:

1534 Bible (Tyndale rev. Joye) Phil. ii. 12 Worke out youre awne saluacion with feare and tremblynge.

1600 Shakespeare Henry IV, Pt. 2 i. i. 181 We..Knew that we ventured on such dangerous seas, That if we wrought out life, twas ten to one.

1805 Wordsworth Waggoner iv. 118 When the malicious Fates are bent On working out an ill intent.

1847 Tennyson Princess ii. 75 O lift your natures up:..work out your freedom.

The last noted use of the phrase by this usage is 1874.

Why did Tyndale choose “work out”? There’s no clear answer. Since κατεργάζομαι is a compound of the prefix κατά and the verb ἐργάζομαι (to work, labor), Tyndale may have added the “out” to reflect the prefix; though he did not translate κατεργάζομαι that way anywhere else. He may have been thinking in Latin: recognizing the meaning of the Greek to approximate the action “to effect,” he may have rendered it first efficere (ex + ficere, to work out) and followed accordingly with the English. Or, he may have just liked the way it sounded. He seems to have had a knack for that.

The Tyndalian wording of this verse, as beautiful and iconic as it is, is now archaic, and tends to obscure the meaning of Paul’s words. Paul clearly was saying that through working — though the praise for our works belongs to God alone, by His grace — we effect our salvation.

I have always admired William Tyndale, first when I was a Protestant and still now that I am a Catholic. Not only was he bold and fearless in his determination to bring the Scriptures into the English language — he ultimately gave his life for that cause — but he was brilliant both as a translator and as a wordsmith. As the first translator of the Bible into English from its original languages, Tyndale has no doubt had more impact on the English Bible than any other single person, and has had an impact on the English language itself to rival that of Shakespeare.