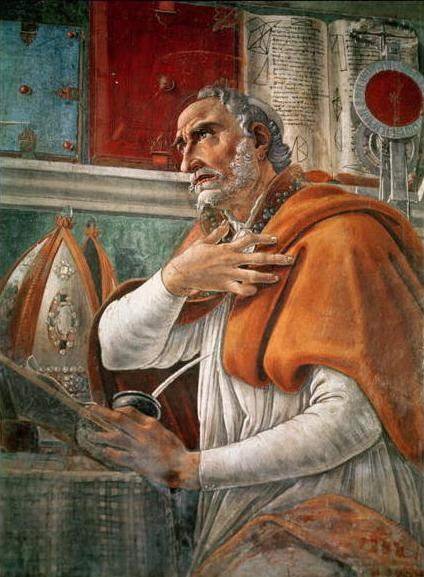

Rembrandt, The Return of the Prodigal Son (1669) (WikiArt.org)

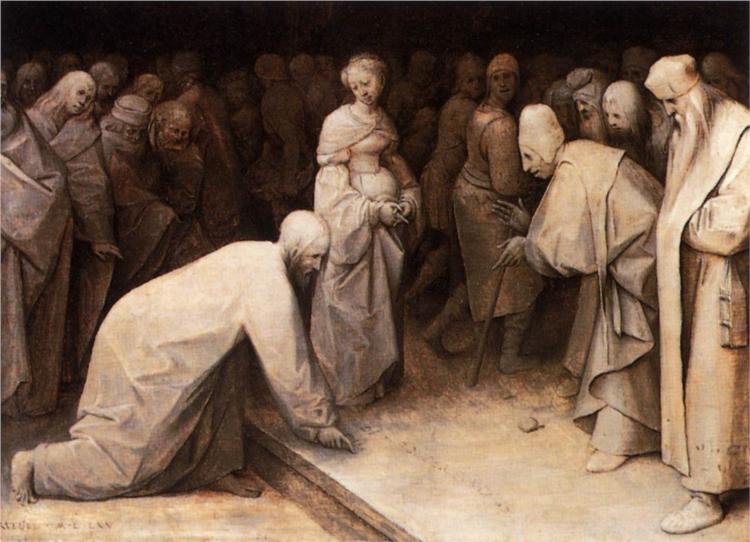

Where I left off, I had more or less fallen away from the Christian faith as a young adult. I still claimed to be a Christian, but I stopped praying; I stopped going to church; I stopped striving for holiness. I had fallen into complacency about sin, and was tired of being made to feel guilty for something I felt I couldn’t control.

What was going through my head? What did I believe? If I believed anything about God, it was that He was good and that He loved me. I believed Jesus, God’s only Son, had died for my sins and risen to new life, so that I too could live forever. Having been raised in church, I had fairly thorough book knowledge of the Gospel, the Bible, and the Christian faith. I believed it. As a teenager, I had prayed the “sinner’s prayer” more times than I could count; I had danced with joy at the foot of the altar; I had spoken in tongues and bore witness to the baptism of the Holy Spirit. By every measure I had been taught as an Evangelical, I was a Christian; I was saved.

But something had gone horribly wrong. I had been wounded very deeply, by life, by sin, by people I trusted, by my church. I had retreated to what I thought was a safe place, into myself, into my room. Daily I self-medicated with TV, the Internet, and addictive, sinful behaviors. I felt powerless to do otherwise. This isn’t the way a Christian was supposed to live — I knew that. I had become a dead branch on the vine, bearing no fruit and only attracting worms.

But Jesus loved me; this I knew. Isn’t this all that mattered? Jesus loved me and He knew me; He knew my inmost being, all the longings of my heart, and all the wounds. Surely He understood me. I was hurt, you see; I was just a sinner — and wasn’t everybody? Surely He forgave me — wasn’t I “covered by the Blood”?

Grace and License

Workshop of Lucas Cranach the Elder, Luther as an Augustinian Monk (after 1546) (Wikimedia).

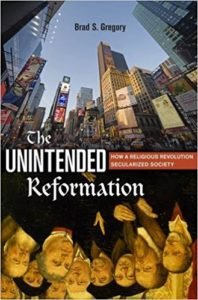

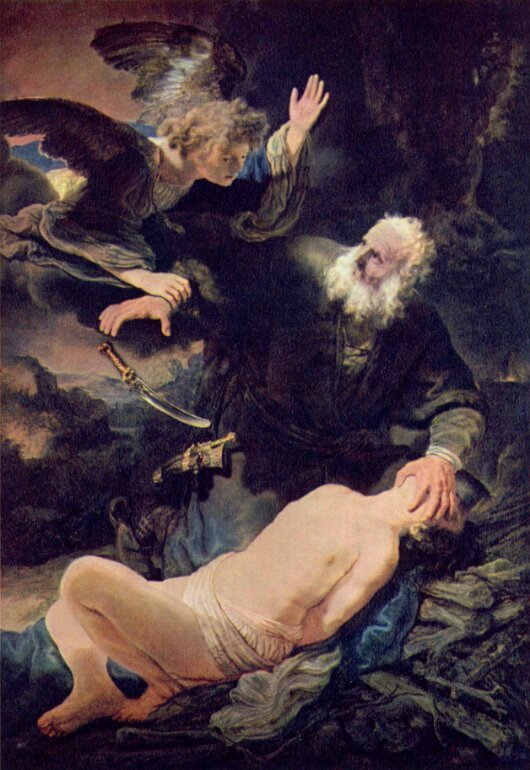

Since the time of the Protestant Reformation, one of the leading charges against Protestant theology is that its teachings about grace and justification — notably, that in justification by God’s grace, every sin he has ever committed in the past as well as every sin he will commit in the future — effectively gives a license to sin. A pastor-friend of mine defends against this charge on Facebook frequently. I am one to agree: this is not what the Bible teaches about grace. This is not actually what most Protestant or Evangelical sects teach about grace.

What they teach is that grace, the love and favor of God, our forgiveness and justification in Christ, is medicine to the soul: that it sets us free from sin and death (Romans 8:2), and that so set free, we will delight in God’s love and grace and bear His fruit gladly and gratefully. No longer bound to sin, we will no longer have any desire for license — even though, it is acknowledged, we still have an inclination to sin (e.g. Romans 7:15-20).

This is the way it’s supposed to work. Redemption by grace transforms us, renews us, gives us a new birth; it fills us with the Holy Spirit, by which we bear His fruit (Galatians 5:16-26).

So what in the world happened to me?

It Didn’t Work

I had fallen. I had fallen into sin; I had fallen away from Christ. I think it’s hard to deny this: though I still confessed Christ, His salvation, and His Gospel with my lips, I denied Him with my life and actions.

For me, my faith in God’s grace did become a license to sin. I never flaunted it; I was never proud of it; but that is what it was. It was a license in the same way that a handicapped permit is a license: a resignation that there was something broken about me, some reason that I couldn’t do what I was supposed to do; I couldn’t live the way I was supposed to live; I couldn’t walk the way I was supposed to walk. It gave me complacency in my disability; it gave me immunity from the consequences of my sin; it gave me no incentive to strive or to fight. If there were no consequences, why even try? I knew that no matter what I did, God still loved me and still forgave me. Breaking free from addiction was hard. It was easier to remain where I was and make excuses. And this was my perpetual excuse: when I hurt myself, when I hurt others — when I bumped into you, or crashed into the walls, like any other disabled person, the truth was I couldn’t help myself — I bumbled, “Whoops, I’m sorry,” but needed only flash my “Sinner Saved By Grace” card, and all was explained.

No, this isn’t a true understanding of grace, in anybody’s version of the gospel. This is a twisted, sick, pathological understanding of grace. But it is a weakness that the Protestant teaching about the finality and immutability of justification, the belief that even future sins are covered by grace, easily falls victim to.

Grace “didn’t work” for me. I did everything I thought I thought I was supposed to do; I confessed Jesus and believed; I prayed the “sinner’s prayer”; I had apparently borne good fruit, for a while. Why did I wither on the vine? Jesus spoke, in the parable of the sower, of the one “who hears the word, but the cares of the world and the delight in riches choke the word, and it proves unfruitful” (Matthew 13:22). This is, it seems, what happened to me. I don’t pretend for a moment that there is any deficiency in the grace of God; any failure on God’s part — though at one time I would have blamed Him for not helping me, for allowing me to fall. No, the failure plainly was my own.

Who Falls Away?

Rembrandt, Judas Repentant,

Returning the Pieces of Silver (1629) (Wikimedia)

The primary thrust of Protestant theology is the insistence that salvation is by grace alone, through faith alone, and the rejection of the thesis that humans have to earn their salvation in any way. This is, in the plainest sense, true. The Catholic Church has always rejected Pelagianism, the belief that the human will can choose God on its own and attain salvation apart from His grace, and her official doctrine has never been different. But in many threads of Protestant theology — dating back to the Reformers themselves — this rejection has a visceral, reactionary quality, denying any role of “works” at all, any involvement whatsoever of human effort. This is an extreme overreaction, and unsupported by Scripture. But it is the ground of the kind of thinking that sets the trap I fell into: If human effort has no role in salvation, then an abandonment of human effort should be no detriment to it.

There are some who teach a dogged, hard-core belief in a doctrine of “once saved, always saved”: that if one confesses with his lips that Jesus is Lord and believes in his heart that God raised Him from the dead, he is saved, and this transaction is irrevocable. No matter how he lives, no matter what he does after that, he is nonetheless saved. Even if he should deny Christ with his mouth and refute his former belief, proclaiming himself an atheist, he is still nevertheless saved. He cannot lose his salvation: he is bound to Christ, even against his will; even if there should be no evidence of it in his life at all.

Gerard Seghers, Repentance of St. Peter (c. 1625-1629) (Wikimedia).

When I was on the bottom, I probably would have affirmed this. It was my only hope. It is the hope, too, of many parents whose children fall away from faith and live lives of profligacy; the hope at funerals for those who never returned. But is it real? I now believe, and Scripture consistently presents, that the evidence of being in Christ is bearing His fruit (John 15:1-6). Faith without works, without fruit, is barren and dead (James 2:18-26). The one who falls away, who denies Christ by his fruit, gives no appearance that he is in Christ at all.

Other Protestants, especially those of the Reformed tradition, present a version of “perseverance of the saints” that argues that the believer who truly has saving faith will persevere to the end; he will not fall away; he will be saved. This at least acknowledges that there are some who do fall away, and that falling away has consequences. But it concludes, rather coldly, that the one who falls away didn’t truly have saving faith to begin with. Thus, it is absolutely consistent, absolutely bulletproof in logic, but absolutely no comfort at all to the one struggling with sin and in real spiritual danger of falling away.

Bernhard Plockhorst, The Good Shepherd (19th century) (Wikimedia)

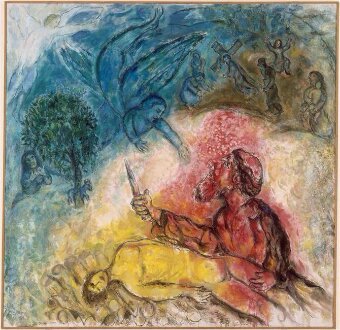

Scripture presents that the one to whom Jesus gives eternal life will never perish, and “no one will snatch him out of my hand” (John 10:28-29). He presented, on the same occasion, that “the thief comes only to steal and kill and destroy” (John 10:10). Satan, the enemy, is real and a real danger, even to Christians. He cannot “snatch the sheep out of the Father’s hand”; no, his threat is, and always has been, more subtle, to entice, to seduce, to cajole the sheep into stepping outside the fold. The grace of Christ is truly amazing; it can truly set us free from sin and death and raise us to new life, and it can protect us, if we abide in Him. But grace does not abrogate our human will or human responsibility. We always have the freedom to depart from His side, to fall away from His path, to reject Him and His grace.

My life is evidence of this. My life is also evidence that even when we sin, even when we reject God, even when we fall away, He never stops loving us, never stops pursuing us, and does not let us go without a fight. Especially for those of us who have tasted His Holy Spirit, who have been regenerated in the waters of Baptism, we are marked with His seal; we are His children; we belong to Him. And He will stop at nothing to reclaim His own. But even when He subdues us by violence, He does not take us against our will, but calls us to return to Him of our own volition.