In this post, I relate how, as a Protestant journeying to the Catholic Church, I came to terms with the doctrine of sola scriptura. I have been trying to write this post for months, and have started over from scratch several times — mostly because it rambled at too great length, or strayed into trite polemic. Catholic apologists tend to repeat and rehash the same complaints — “sola scriptura” isn’t scriptural! The Early Church functioned just fine for a period of decades before the New Testament was written and compiled! No Christian held to such a constraint prior to the Protestant Reformation! — and though I do think these arguments are persuasive now, I was not even aware of them then, and they played no role in my own convictions.

This post proved to be really long, so I split in into two. I will post the second half soon.

Part of my ongoing conversion story.

Approaching the Church

Giovanni Paolo Pannini, Nave of St. Peter’s Basilica, Rome (1731). (Wikimedia)

At last, I had stumbled my way into the Mass, and found in it something glorious and transcendent and compelling. I began to attend Sunday Mass on a weekly basis. All the fragments that had been circling around me my whole life seemed to be falling into place. I felt peace. But this is still not yet the end of the story. I had some final hurdles to overcome, confronting Catholic doctrine head-on as it came to bear on what I held as a Protestant.

I hadn’t been attending Mass very long at all, perhaps only about a month, before one day I happened to speak to Father Joe. I had not sought him out; Audrey and I had been standing there outside the church chatting, and he asked me what I thought so far. I blurted out that I liked it and was thinking about joining the RCIA class. I was alarmed to hear myself say it; I don’t think I had even articulated the thought before that. I understood that this didn’t mean I was making a commitment; that there was still plenty of time to learn and change my mind; but as I had at so many moments before, I felt a sinking feeling that I was approaching a point of no return.

This was still early in the year, about March. The next RCIA class would not begin until September. So over the next six months, I committed myself to reading and learning as much as I could, and to experiencing as much of the Mass and of the Church as I could. I began attending daily Mass also at every opportunity I could. At St. John’s they offered Mass every weekday, and being just on the edge of campus, I could run over almost anytime. My reading took on a new focus. Up to this point, I had still not read any “Catholic” book. I had not read any of the Catechism or any apologetic work. I had not read any of the great body of conversion literature, the writings of other Protestants like me who had made their way to the Catholic Church. Rather than the end of my journey, I was really only beginning my approach in earnest. I was just beginning to consider the Catholic Church with an open and discerning mind. I did not jump in head first. As it should have, my exploration of the Catholic Church soon came into confrontation with my convictions as a Protestant.

Sola Scriptura

(Source: peachknee on Pixabay)

I was no dummy. I understood that to embrace Catholic doctrine entailed a renunciation of what was has been called “the formal principle of the Protestant Reformation”: sola scriptura, the thesis that Scripture alone is to be the sole source of divine truth for the Church and for Christians. I knew well, as all Protestants know, that this is one of the fundamental disagreements between Catholics and Protestants: that Protestants hold as authoritative the Bible alone, while Catholics deny this and add other things.

But looking back, I don’t recall ever having much of a serious struggle with sola scriptura. On the contrary, it seems to have folded quite readily and early on in my final approach to the Church. Why? Could it be true, as some have charged, that I never had a firm commitment to Protestant principles in the first place? Or were there other forces at work in my life, under the surface and behind the scenes, preparing the way before me and making it straight to the Church? The truth is, whether I openly acknowledged it or not, that I had been struggling with sola scriptura for years. I can think of several factors underpinning the idea of sola scriptura that I had already been dealing with, and that had already weakened that foundation, long before this point.

A Flimsy Default

(Source: mnplatypus on Pixabay)

If I had ever been asked about the source of my Christian doctrine as a Protestant, I would simply have pointed to Scripture. Because what else was there? This was the default position, what Protestants did, the only thing I knew. Where else would one possibly look? But if I had been asked to explain why, I would have been a little dumbfounded. Because it’s the Word of God, God’s message to mankind? Obviously, when one is looking for source material about God and Christianity, the Bible is your source. This seemed to be a reasonable proposition at the time.

But why did I believe that? Why Scripture alone? How did I know? I would have been hard-pressed to defend it. The only thing I knew, the only thing I recall ever hearing, was that Martin Luther proclaimed sola scriptura in opposition to the “unscriptural doctrines” of the Catholic Church. Did the doctrine really only exist as a negative? Was there no positive reason for it to stand on its own? It is possible that some Protestant apologetics might have shored up the position for me, but generally I have found Protestant apologetics on this matter unsatisfactory. Every Protestant argument I have read in support of sola scriptura inevitably begins with or returns to the point that “the Catholic Church believes unscriptural doctrines.”

“Unscriptural doctrines”

Juan de Juanes, Christ and the Eucharist (16th century) (Wikimedia)

The rote line of Protestant lore, what I recall hearing all my life, is that Martin Luther proclaimed sola scriptura in opposition to the “unscriptural doctrines” in the Catholic Church. It was often told, even in my mostly ahistorical corner of Protestantism, how Luther discovered the truth of God’s grace and salvation by faith alone by reading Scripture — the implication being that Catholics did not read Scripture, that the Catholic Church had entirely thrown the Bible out the window. I believed this because I knew nothing else.

But by the time I was in my thirties, having spent all my life as a Protestant, and for several years having exerted a lot of effort trying to attain a more academic grasp of Christian theology, starting from scratch, I had become inured to this charge of “unscriptural doctrines” — since the sad truth is, many Protestant sects accuse each other of believing “unscriptural doctrines,” even those who proclaim sola scriptura — the fact of the matter being not that these believers didn’t read Scripture, but that they read and interpreted Scripture differently. I had struggled mightily for years to sort out the truth among many such competing interpretations, ultimately concluding that in most cases, these couldn’t be called “unscriptural doctrines” at all, but the result of ambiguities in Scripture and good-faith differences of opinion.

And I came to realize that Catholicism was probably the same way. I knew, from studying the history of Christianity in school, that Catholics believed that the bread and wine in Communion actually became the Body and Blood of Christ — and reading Scripture for myself, I could see how that could be a defensible reading: Jesus did say, “This is my Body,” and it is only by assuming premises not in Scripture, that He was speaking symbolically or metaphorically, that one concludes otherwise. I came to expect that the same might be true for other supposedly “unscriptural” Catholic doctrines: what if they were only as “unscriptural” as what Protestants accused each other of? And if that was the case — what was the cry of “sola scriptura” really all about?

Paralysis

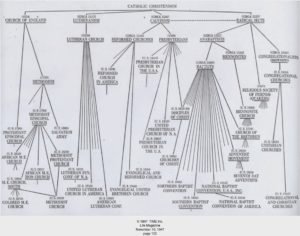

Perhaps the strongest argument against sola scriptura, the reason that led to the doctrine’s downfall in my mind more than any other, was my growing conviction that sola scriptura just doesn’t work. I probably would not have put it in those terms as an Evangelical — such would have seemed heresy — but the fact of my experience is that I found myself completely unable to discern between the claims of competing denominational camps to have the exclusive, correct interpretation of Scripture. Sola scriptura — relying on Scripture alone — proved unable to bring me to any conviction of the truth, so far as any certainty or precision of doctrine or theology was concerned. Historically, it had proved unable either to unite the Protestant cause or to preserve any degree of unity at all in the Church. If anything, the doctrine of sola scriptura itself is the single most culpable culprit for the continued fragmentation and division of Protestant churches, both historically and contemporarily — since any believer with his own divergent interpretation of Scripture feels entitled to break away and found his own sect.

The Baptists, the Presbyterians, the Methodists, the Pentecostals, all came to different, sometimes radically different, interpretations of the very same passages of Scripture. And I found myself completely unable, in many cases, to choose one over another, to declare one right and another one wrong. And this was not on account of any ignorance or lack of preparation on my part (though a lack of indoctrination into a particular interpretive tradition, I suppose, could be credited): I had studied the original languages and trained in translating ancient texts; I had studied history and the historical contexts of the Early Church and the ancient cultures in which it dwelled. If anything, it was on account of that preparation that I had less confidence than some of my peers, who were able to affirm their churches’ particular interpretations with conviction. Such people and churches could make strong, valid arguments for their positions — but so could all the others.

I was forced to conclude that in many cases, Scripture was not “perspicuous” at all, but that in many locations the text was ambiguous enough to allow more than one valid interpretation. To weigh between multiple, valid interpretations of the words requires something more than the words themselves: it requires a consideration of the wider textual context, both in the same text and in other texts. It requires a consideration of the historical and cultural contexts, and an understanding of the way the text was received by its earliest recipients. And ultimately, it required having an opinion, and being willing to draw conclusions based on it — and though I did have opinions, they were neither strong enough nor certain enough for me to stake my eternal life or death on them with anything like security. I realized that scriptural exegesis is not an exact science, and the “right” interpretation is often not clear from the text at all, as the popular view of sola scriptura would lead me to believe: it ultimately, and inevitably, involved making my own understanding the final authority in interpreting Scripture.

There is a lot more to come! You can expect the next post in a day or two.

You should take care not to overlook the struggles of the Early Church with heresies concerning scriptural interpretation, the existence of scripture in the Church from the beginning (Christ was taught as the fulfillment of scripture, from the start, Psalms have always been a cornerstone of liturgy), and you cannot overlook differences among orders, varying degrees of mysticism, and theological differences which continue even within the imagined monolith of Catholicism.

Sola scriptura is a commitment to truth. Even the canon, in earliest forms was a polling of the churches and agreement on what had been received. That is critical. What is received by all, homologoumena, is a revelation that denies inner lights, personal interpretation, and private and ongoing revelation, not one that promotes these things. This is a bulwark against the new gnosticism of New World sects (calling Pentecostals or even most Baptists “Protestant” is a stretch – they have very little in common Lutheranism and only a little more to Calvinism).

Scripture corroborates and interprets itself. there is nothing, no doctrine that stands alone based on a proof text. This is the position which led Origen to poll the churches, to worry about scribal errors. It led Augustine to his remarkably humble position and acknowledgement, along with Jerome and others of anitlegomena (opinions embraced by later scholastics, pre-Trent).

Doctrinal differences all stem from a pursuit of truth. Yet, I am convinced that there is nothing lacking in scripture. There is no “Protestant cause” in the sense that many groups chose separation as their goal and conformed their reading of scripture according to that hermeneutic. The ecumenism of most mainline churches and the appeasing accords with them from Rome testify merely to the desire to establish alternatives. This is not a principle of sola scriptura as a rule of faith. It actually tries to work in reverse. A prime example is that no reading of scripture, no exegesis from scripture, yields a sacrament that is a mere symbol or something subject to Calvinist receptionism – the body and blood of Christ are, unambiguously present in the sacrament and are received by all in the distribution of the elements. Any “interpretation” to the contrary or claim that this is an unscriptural teaching is not from any point of sola scriptura. Rather, it requires a reading into, not a reading from scripture to arrive at this conclusion.

We have, in scripture, the testimony of witnesses and confessed apostolic writing. It is this testimony that we have been given to confess. The Lutheran criticism of “unscriptural” teachings and practices pertains to those not attested to in scripture or those that run counter to scripture. Likewise, a Lutheran criticism of “unscriptural” teachings in many other churches would be those teachings that result from a flawed exegesis that fails to account for the Word as a whole and in context, history, language, and culture.

So, while you see in the divisions reasons sola scriptura fails, I see more and more reason to believe it is true. There is no aspect of Law, Gospel, sacrament, prayer, or Christian life which is not clearly apparent in scripture. I would recommend a reading of Martin Chemnitz’s critique of Trent with respect to scripture for a solid perspective on the doctrine uncorrupted by Reformed and radical churches.

Hi, Hlewis. Thanks for the comment.

Regarding the struggles of the early Church with heretics: Both Irenaeus and Tertullian, writing specifically about the Early Church’s struggles with heretics (Irenaeus in Against Heresies and Tertullian in The Prescription Against Heretics), affirm that “Scripture alone” was completely inadequate in reasoning with heretics — since, according to Irenaeus, “they turn round and accuse these same Scriptures, as if they were not correct, nor of authority, and [assert] that they are ambiguous.” According to Tertullian, “with respect to the man for whose sake you enter on the discussion of the Scriptures with the view of strengthening him when afflicted with doubts, [whether it will be] to the truth, or rather to heretical opinions that he will lean … he will go away confirmed in his uncertainty by the discussion, not knowing which side to adjudge heretical.” These are the very same problems with Scripture alone I have described here, encountered in the second and third centuries! For the solution, both men turn not to Scripture alone, but to the authoritative teaching of the Church handed down in apostolic succession. (For the full quotes and their expositions, see my post Some Early Testimonies to the Authority of Apostolic Tradition).

Yes, the Church has rightly held Scripture in high regard as the Word of God from the very beginining. But the Early Church very plainly didn’t hold to anything like a Protestant standard of sola scriptura — as several Protestant apologists I have read have inadvertently acknowledged, calling out the Churches of the second century for “already falling away from the truth of Scripture” in adopting a hierarchy of authority under a single bishop!

And no, Catholicism is not a monolith: it is a beautiful tapestry which despite its diverse elements, continues to work together as one even after so many centuries; whose diverse orders, various mystics, and myriad theologians can all together affirm a common creed and faith. Contrast Protestantism, whose many sects can affirm very little if anything in common, which continually seek to divide rather than to unite, and many of whose sects, even in this very comment, you have disowned as heretical. Protestantism knows only how to divide. (By the way, you have just disowned me as a Protestant and most of the people I know. My point is proven.)

No, Scripture does not “corroborate and interpret itself” — as evidenced by the plain fact of such a profound lack of any agreement among Protestants and so many diverse and mutually exclusive interpretations. Whether you accept many such interpretations as “scriptural” or not, as valid applications of “sola scriptura” or not, or whether their exegesis is flawed or not, the fact is that these churches do claim to be following a principle of “Scripture alone,” and point to “Scripture alone” for their interpretations — as the principle of sola scriptura, first propounded by Martin Luther, entitles them. You are doing exactly what all Protestants do: affirming the truth of your own church’s interpretation by Scripture alone while rejecting every other church’s as “unbiblical.”

I’m sure you’re aware that the idea of the Sacraments as “mere symbols” is a product of Zwinglian theology — Zwingli, of the first generation of Reformers, generally held to be in the “Reformed” camp, which even in its Calvinist branch, rejected many of the tenets of the Lutheran branch. From the very beginning, these people could not agree on how to interpret Scripture or how to “reform” the Church. You’re quite right that there has never been a single “Protestant cause” — other than the presumed goal they all had to reform Christianity. Division, disunity, disagreement, and destruction are all they ever accomplished. And you don’t see in this a failure?

If anything is “clearly apparent” in Scripture, by Scripture alone, to whom exactly is it “clearly apparent”? In fact, many groups claim to have such “clarity” — and they meet in different buildings and partake of different tables and do not have fellowship with one another. To someone not already inculcated in your sect, why should your claim to the sole and exclusive “clarity of truth” be considered any more valid than anyone else’s?

I’m not sure if you meant to, but your comment has only underscored all the reasons I wrote about. But I feel I’ve come across in this comment more harshly than I meant to. God bless you, and thank you again for the comment. I wish you the peace of Christ and unity with His Body.

Pingback: Grappling with Sola Scriptura, Part 3: An Authoritative Church | The Lonely Pilgrim

Pingback: Grappling with Sola Scriptura, Part 2: Sources of Authority | The Lonely Pilgrim

Pingback: Grappling with Sola Fide, Part 1 | The Lonely Pilgrim

Very powerful, honest, and insightful

Thank you for writing this list.

I have independently come to a similar conclusion.

Only the Catholic Church and Eastern Orthodox Church can provide a continuous line back to Jesus and provide adjudication in all of these contentious issues. This adjudication relies on historical precedent (how did early church fathers handle these controversies?), scriptural analysis, and reason, but any of these alone would be inadequate.

I have been searching for this type of information for two years… and here you are. I know this is an older article but it is exactly what I needed to read to assess a few problematic areas in my life. I too converted to Catholicism – and my father and I argue over Sola Scriptura at least once a year. God Bless you and yours.

Thanks so much for your kind comment. God bless you too.