The post I meant to make before I was distracted by Luther.

This Lent I’ve been re-reading the Pentateuch, since the last time I read it was before I was Catholic and before I had the benefit of Catholic Bible commentaries or an elementary knowledge of the Hebrew language. In reading the story of Abraham in Genesis, I got to thinking about the nature of Abraham’s faith:

“And [Abraham] believed the Lord; and [the Lord] reckoned it to him as righteousness.” (Genesis 15:6)

Justified by Faith

The Apostle Paul prominently appeals to this verse in his discourses on the doctrine of justification in his epistles to the Galatians and Romans (Galatians 3:6, Romans 4:3). It is an especially important verse to the Protestant concept of imputation, the idea that when a sinner comes to faith in Christ, the righteousness of Christ is imputed to the sinful believer, “covering” his sins like a cloak rather than actually transforming him; that the righteousness of Christ is credited to his account by a forensic, legal declaration only, such that he is considered “righteous” by God’s juridical reckoning on account of Christ’s righteousness, despite God still seeing the sin that fills his life. Per Luther’s argument, even “a little spark of faith,” a “weak” or “imperfect” faith, the “firstfruits” of believing in Christ, was sufficient to bring about this imputation, counting a sinner righteous once and for all.

In Paul’s context, he argues that Abraham was counted righteous before God not because of any works he performed, but because of his faith in God’s promises. And, it’s true, both in the Hebrew of Genesis and the Greek of Paul’s letters, the verb translated “reckoned” is one of reckoning or perception: Abraham’s faith was counted as righteousness.

But then, it begs the question: if Abraham’s faith was imputed to him as righteousness, and this imputation is analogous to a believer’s justification by faith in Christ, what kind of faith did Abraham have? Was it a “weak” or “imperfect” faith? Did the imputation to Abraham of righteousness that followed his faith belie and cover an otherwise sinful state in the man? And, once this faith was imputed to Abraham as righteousness, was he then “counted as righteous” from then on, he being unalienably in God’s favor from that point forward? If the faith of Abraham and its imputation to him as righteousness is an analogy to the justification of a Christian believer, then we should expect both the faith and the imputation to be similar.

A Total Commitment

It’s clear, however, that the faith of Abraham that was counted as righteousness was not an weak or imperfect, not an initial and insecure belief in God’s promises, as Luther would present, but instead a total commitment of his life and his destiny to God’s plan. The reference to Abraham’s faith being reckoned as righteousness occurred only after he had obeyed God and left his home far behind for a distant land. And his position before God was not that of a lost and abject sinner, but of a man who had dedicated himself in faith to total obedience to God’s commands. If his faith was reckoned to him as righteousness, then surely it was because wholly committing himself in faith to God’s promise was a righteous thing to do.

An Active Faith

And was Abraham’s reputation as righteous then permanent and irrevocable, because of his singular act of faith? Was he then forevermore in God’s favor, to be considered blameless even if he should fall away and reject God’s promises? In fact, God made a covenant with Abraham, binding Abraham to a set obligations.

And God said to Abraham, “As for you, you shall keep my covenant, you and your offspring after you throughout their generations. This is my covenant, which you shall keep, between me and you and your offspring after you: Every male among you shall be circumcised” (Genesis 17:9–10).

By the nature of a covenant, God’s promises to Abraham were contingent on Abraham’s remaining faithful to it. Abraham continued to be counted as righteous because he continued to keep his faith with God. In fact, we find very clearly, elsewhere in Scripture, that Abraham’s faith was considered righteous because it was an active faith:

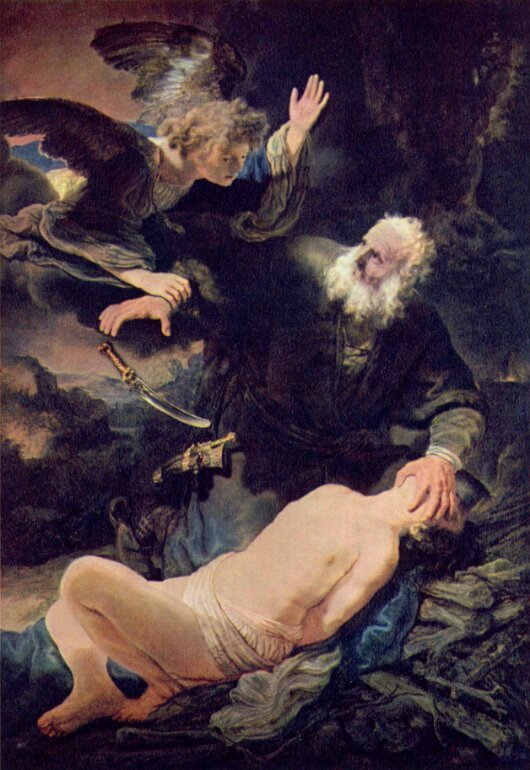

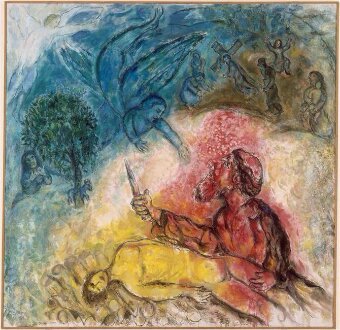

Was not Abraham our father justified by works, when he offered his son Isaac upon the altar? You see that faith was active along with his works, and faith was completed by works, and the scripture was fulfilled which says, “Abraham believed God, and it was reckoned to him as righteousness”; and he was called the friend of God. You see that a man is justified by works and not by faith alone (James 2:21–24).

The Works of Torah

What, then, was Paul talking about when he said that Abraham was justified “by faith … apart from works”? What “works” was Paul rejecting, “that none should boast”? It’s clear from Paul’s context that he refers very specifically to the works of the Law — νόμος (nomos), which in a Jewish context, referred almost exclusively to the Torah (the word θεσμός [thesmos] being the more common word in Greek for human laws, rules, rites, or precepts):

The promise to Abraham and his descendants, that they should inherit the world, did not come through the Law but through the righteousness of faith (Romans 4:13).

In particular, the work of Torah with which Paul is most concerned is circumcision, which in the case of Abraham, had not even been commanded yet, when “he believed God and it was reckoned to him as righteousness.” In Paul’s context, circumcision was being preached by the Judaizers as a necessity for salvation in Christ. In other words, Christ was the Messiah of the Jews, and to become a follower of Christ, per their argument, one must first become a Jew. Not so, said Paul:

For we hold that a man is justified by faith apart from works of Law. Or is God the God of Jews only? Is he not the God of Gentiles also? Yes, of Gentiles also, since God is one; and he will justify the circumcised on the ground of their faith and the uncircumcised through their faith (Romans 3:28–30).

With a Faith Like Abraham

What Paul is saying, then, is that to inherit the covenant promises of God, one does not have or be a descendant of Abraham according to the flesh, either by blood or by circumcision (Romans 9:8). Rather, it is the children of the promise, who follow in the faith of Abraham — with a faith like Abraham — who inherit: a total commitment of one’s life and destiny; a placing of all one’s faith and hope in God’s promises; a faith active in love (Galatians 5:6).

Do you have any sources for your work? Your work here reminds me a lot of the new perspective on Paul stuff by NT Wright. Good stuff.

Thanks for the comment, and welcome! I know of Wright, but have not read him. I speak only from my own reading of Scripture in the Catholic tradition. God bless you!

Well that makes since. Wright actually speaks of interpreting without a reformer lense. Its far more friendly towards elements of Catholic tradition though he is himself Anglican.

Thanks. I’ve been meaning to read Wright at some point. Come to think of it, I do owe a reference to Jimmy Akin’s The Salvation Controversy . It’s a very good summary of the Catholic position on Paul and justification, framed in terms understandable to Protestants.

. It’s a very good summary of the Catholic position on Paul and justification, framed in terms understandable to Protestants.

Joseph, you’ve written above:

The question is excellent, if incomplete. The question isn’t just, “what kind of faith did Abraham have?” It should also include, “what was the object of Abraham’s faith?” I think we can agree that the answer to the second is equally as important as the first.

Allow me, if you will, to try to answer a couple of the questions you’ve posed above, and to do so by working through the backwards. You ended by asking, “Did the imputation to Abraham of righteousness that followed his faith belie and cover an otherwise sinful state in the man?” I’m not certain that your answer (an appeal to Genesis 11:1-9, which is put forward as an example of Abram’s obedience) does justice to the intervening features of the text found in Genesis 11:10-20. Let’s not forget that immediately after Abram leaves Ur, he sojourns into Egypt where he lies about his relationship to Sarai, claiming that she was his sister rather than his wife.

You also asked, “what kind of faith did Abraham have? Was it a “weak” or “imperfect” faith?” Again, the subsequent context in Genesis militates for an emphatic “yes” in answer to the question posed. What happens after the promise of a child is made with Abram in Genesis 15? Abram is persuaded by his wife that he should fornicate with Hagar so that Sarai could “obtain children through her.” (Genesis 16:2) Keeping in mind that the promise to Abram was that Abram would have a son and that Sarai was going to be the mother of this child seems to be implied by her coming to Abram to request that he and Hagar spend some time in the tent together, the record does seem to indicate that Abram’s faith was in fact weak and imperfect, especially since he acquiesces to his wife!

It is precisely these features of the text that lead Protestants like myself to posit that Abram was justified by a weak and imperfect faith; it seems to be the only reading of the text that makes sense of the context as a whole.

Here’s hoping this finds you well!

BMPalmer.

Thanks for the comment and the brain-pickings. In the senses you relate, certainly Abraham’s faith was weak and imperfect — as the faith of any weak and imperfect human must be (I do not mean to imply the opposite, that his faith was perfect!). But I still maintain that the kind of imperfection Abraham evinces doesn’t approach the “imperfection” that Luther referred to (this, admittedly, after my very select reading in his Commentary on Galatians). Luther spoke of the first stirrings of faith, the very beginnings of a sinner’s coming to believe in Christ while still lost in sin. And that doesn’t seem to me to be very analogous to Abraham’s situation. Despite his many weaknesses, he was willing to pull up stakes and leave his home out of faith in God for a far-off promise.

My biggest problem with Luther’s idea of imputation is that an imperfect, initial faith could suddenly and permanently “cover” all a sinner’s sins from then on, regardless of his continuing fidelity. It casts God in the role of “winkingly” (Luther’s description) overlooking the sinner’s wretched state, heaping all his greatest promises and rewards on him, and then dumbly following along pretending the sinner is faithful to the covenant whether he actually is (or is even making an effort to be) or not. Even beyond that, the concept of imputation as I understand it does not account for the transformation of life that rebirth in Christ certainly brings in a believer — sins not just “covered” but washed away, and grace and its fruits brought forth in his life. It all seems to me to be very poorly supported by Scripture, let alone real-life observation, and leads me to suspect it all to be part of Luther’s attempt to free himself from self-condemnation.

Hope all is well with you also. God bless you and His peace be with you!