Today, October 31, is the 499th anniversary of the start of the Protestant Reformation, the day Martin Luther is said to have nailed his Ninety-Five Theses to the door of the Wittenberg church door, the beginning of the “protest” — celebrated as, in Lutheran and Reformed churches, Reformation Day. Yesterday was known in those churches as Reformation Sunday. I, for one, celebrated Reformation Sunday by welcoming a Protestant brother into full communion with the Catholic Church. And today I am reflecting on the troubling celebration of “Reformation Day,” on the heritage of the Protestant Reformation, and on my own Protestant heritage.

Confirmed in Faith

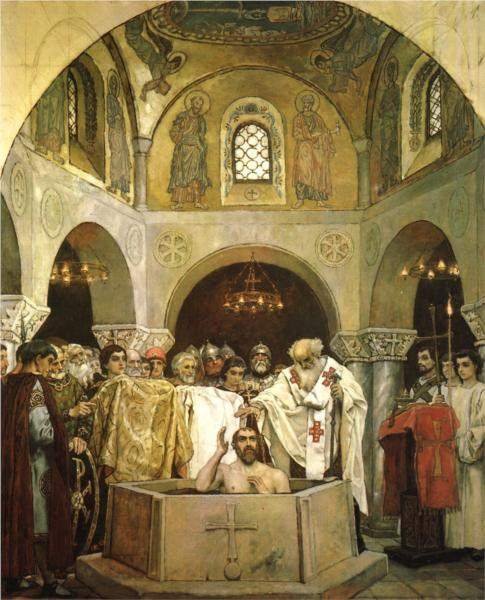

Yesterday my friend Jason Parker was confirmed in the Catholic Church by our bishop, the Most Rev. Robert J. Baker of the Diocese of Birmingham in Alabama, at Our Lady Help of Christians Church in Huntsville. Jason was raised Southern Baptist, but as I was, had been being drawn for a long time to the history and liturgy of Catholic Church. I met him about a year ago, working at the University of Alabama in Huntsville, where he has been my officemate. I can’t take much credit for converting him: he was already very far along his journey when I met him, and only had some nagging questions I was able to help him through.

Jason’s Baptist family, by all appearances, was remarkably supportive of his decision. About half a dozen of them turned out for the Confirmation Mass — a Tridentine High Mass, at that — including parents and grandparents. It testifies to me, and rightly so, that faith in Christ is the highest treasure, whatever form that faith might take. My own family and friends have also been very supportive of me. On my own road to the Catholic Church, the friend whose opinion I was most concerned about was my good Baptist friend Josh’s — but when I confessed my inclinations to him, he most graciously told me that wherever God was leading me, he would support me.

Protestant Heritage

There were some moments, during my own journey, when I felt real concern for what my ancestors must think of me. As someone very close to my roots who has been involved in researching my genealogy for the past twenty years, I often feel I know my ancestors personally, and it is easy to think of them looking down on me. And it is a certain fact that especially in generations past, Protestants viewed Catholicism with even more suspicion and mistrust than they do now, if not outright judgment.

Cathedral Basilica of the Immaculate Conception, Mobile, Alabama (Wikimedia).

What would they think of me, these men and women who lived their whole lives believing in Protestant churches? Was I betraying my heritage? Was Protestantism in my blood, a part of who I was, the religion of my people and region and culture? Growing up in the Southern United States, I thought, and there is still the perception to some, that Catholicism is a “Yankee” phenomenon. And it is true, thanks largely to Irish immigration in the nineteenth century, that there tends to be a higher concentration of Catholics in the northern states. But the truth is, some of the earliest beachheads of Christianity in America were Catholic and in the Southern U.S., at New Orleans and Natchez and Mobile and Pensacola and St. Augustine. Catholics are much more of a minority in the upland South from which I hail, but even in my own backyard, German immigrants established a Catholic stronghold in North Alabama at St. Bernard Abbey in Cullman; and Mother Angelica built a global fortress at EWTN in Irondale. Catholics have been making inroads here: in every parish of which I’ve been a part, we have seen a bumper crop of new converts in RCIA. And it so happened that I stumbled into perhaps one of the most proudly Southern Catholic parishes around: St. John the Evangelist in Oxford, Mississippi, home of “Ole Miss,” the University of Mississippi, and Southern Fried Catholicism.

I have some half a dozen Protestant ministers in my ancestry — four Methodist and one Baptist that I can think of, off the top of my head. They seem to have been good men full of faith. One of them, through a weird trick of God’s Providence, is buried in the cemetery of my Catholic parish today. That fact, more than any other, confirms me in the conviction I eventually came to: that if it is true, as I believe, that the Catholic Church teaches the fullest, clearest, most faithful presentation of the truth of Christ, then my loved ones in heaven, my faithful ancestors, surely now understand the truth. Coming to perfect knowledge in death, believers are surely undivided in Christ in heaven.

Gloating in Division

Georg Heinrich Sieveking, Execution of Louis XVI (1793) (Wikimedia).

One of the things that bothers me most about “Reformation Day” celebrations is the triumphalism: the proclamation, even in this day, that the Reformation was about “the rediscovery of the Gospel from the darkness of man-centered righteousness!,” to quote a friend’s Facebook post. This is the popular narrative, seemingly immutable, in some Protestant churches, especially those of the Reformed variety. It amounts, in my view, to dismissing the Catholic Church as a dead and lifeless corpse, gloating in our division of the Body of Christ, and laughing mockingly on the gallows of our matricide.

I strive to point out, to anyone who will listen, that the idea of the Catholic Church as having “lost” the gospel or of teaching a “man-centered righteousness” is mostly an historical and theological myth, rooted almost solely in the polemical writings of the Reformers and in the continued distortion and misunderstanding of Catholic theology. The Catholic Church does not teach, and has never taught, that our righteousness or our salvation is based on our own works.

The suggestion that the Catholic Church had “lost” the gospel is deeply troubling, and it is bandied around without appreciation of its implications. Did Christ really allow His Church to fall into apostasy? The gates of hell to prevail against her? The light of truth to depart from the world? Did He really allow generations of believers to believe in vain and to be condemned? These charges of a “lost gospel” are usually not fleshed out. What is it, precisely, about Catholic teaching that allows the gospel to be “lost”? For how many centuries was the earth without the gospel? It is a polemical, divisive, and ultimately unjustifiable point.

Workshop of Lucas Cranach the Elder, Luther as an Augustinian Monk (after 1546) (Wikimedia).

Of course, in Protestant mythology, the idea is that the Catholic Church was never the One Church of Christ at all, that it was merely a human institution and usurper to the name “Church,” that the true Church exists as an “invisible” body in the hearts of true believers, and that there have always been “true believers” apart from the Catholic Church. Thinking thus, the idea that the “Roman Catholic” Church could “lose” the gospel is not so profane a thought. Such thinking invariably requires believing facts not supported by the historical record, or else ignoring the historical record altogether.

The schism of the Reformation happened. I don’t believe it was God’s will (although God has made the most of it, despite our human failures). We allowed petty human disagreements and politics to rend the Body of Christ, when Christ prayed “that we might all be one, as He and the Father are One” (John 17:21). Yes, there were some corruptions in some sectors of the Catholic Church — as there almost always are, where sinful people are involved. Yes, the Church is always in need of spiritual renewal and revival. But the tactics of various Reformers, a wanton disregard for Christian unity or reconcilation, did much more harm than they possibly could have done good. Reform was possible without schism. Regardless of Protestant insistence that Luther and other Reformers were seeking reform within the Church and did not seek to found their own churches, Luther made little if any conciliatory effort toward the established order of the Church: If he was seeking reform on his own terms, then schism is what he actually sought, and schism is what he got.

The Heritage of the Reformation

I do become angry and indignant at such arrogant assertions as these. But as I’ve said many times before, I’m very thankful for my Protestant upbringing and for my Protestant heritage. There have been positive fruits of many of the various Protestant traditions. I would like to briefly recall a few.

Scripture Study

It is true, I believe, that the Protestant Reformation brought about a much-needed renewal. Its emphasis on the written Word of Scripture — combined with, and fueled by, the recent invention of movable type — certainly put the Bible in the hands of many believers who previously could not read it for themselves, and in the vernacular languages known to them. There is a lot of Protestant mythology, too, about the Catholic Church striving to keep the Bible from the hands of believers, which simply isn’t true. But the wide availability of Scripture in vernacular languages, and the ability for believers to draw closer to God through Scripture study, is certainly in part a fruit of the Protestant Reformation.

Reform of Corruption

Some of the charges of the Protestant Reformers, about corruption in the Catholic Church, were on target. I do not believe, and the historical record does not support, that such corruption was as pervasive or widespread as the polemics of the Reformers would have us believe. But it is true that many pastors and even bishops were ignorant or uneducated and not equipped to faithfully teach the truth of salvation to their flock. The true teaching of the grace of Christ, then, may indeed have been neglected from the popular piety of many. There was certainly political corruption, especially in the leadership of the Church, in simony, the buying or selling of ecclesiastical offices or benefices; pluralism, the holding of more than one church office, and not doing any of them very effectively; and absenteeism, the holding of a church office, but not living in or being involved with its ministry. There were indeed abuses of indulgences, that had been known for a long time but little had been done to correct them. These and other matters were certainly reflective of a need for reform.

Renewal

Matthias Burglechner, The Council of Trent, 16th century (Wikimedia Commons).

Perhaps it is true that the Church was slow to reform herself — but these and other matters of concern raised by the Protestant Reformers were dealt with at the Council of Trent and implemented by the Catholic Reformation. The Protestant Reformation did eventually spur this reform — but the way it was carried out put the Church into an immediate crisis mode and probably delayed meaningful reform by a generation. A more graceful and patient reformer, I believe, could have worked within the Church to bring about this reform without schism.

I also suspect, having come from the Protestant camp, that Catholic doctrine, worship, and practice has benefited a lot from its interplay with Protestantism. Prior to the Reformation, Catholic theology certainly held that salvation was by grace, through faith. Luther “discovered” nothing, except a novel and unprecedented interpretation of Pauline theology. But in the Catholic teaching of grace, its immediacy and intimacy may have been obscured by endless, scholastic, theological inquiry and speculation. I don’t know much about what would have been taught to lay believers in parishes at this time: but I am sure that the concerns of the Protestants did bring about a renewed focus and a reemphasis on grace.

I am glad, personally, for the emphases in my faith that my Protestant upbringing taught me. I am glad for the emphasis on an intimate relationship with Christ (though this is certainly not unique to Protestantism); I am glad for the emphasis on personal Bible study. I am glad for the faith of my parents and grandparents that brought me to know the Lord. But I pray every day that divided Christians can draw closer together, come to better understandings of one another and forgive each other, and take steps toward working together for the gospel of Christ, and ultimately toward the restoration of the united Body of Christ. “Reformation Day” can be useful to celebrate the heritage of the Protestant tradition, but as a celebration of disunity I find it only harmful.