Last time, we examined how, in the usage of the New Testament authors, especially Paul and Luke, the churches of Christ were often referred to in the plural, not as a single body — giving rise to a common Protestant claim about the independence of the New Testament churches — yet how Paul’s frequent exhortations to be of one mind betray a certain sense of unity among all Christian believers. This is made clearest in the words of Christ Himself: “I do not pray for these only, but also for those who believe in me through their word, that they may all be one, just as You, Father, are in Me, and I in You, that they may also be in Us” (John 17:20–23).

Many Protestants tend to read these appeals to unity as references to a vague, undefined, invisible “unity” that somehow contains all believers “in the Spirit,” regardless of the depth of their actual division and disagreement. But such notions of “unity” do not fit with or maintain the biblical call for a true oneness in mind and spirit; they are not the reality of the Church Jesus founded or Paul exhorted.

One Body

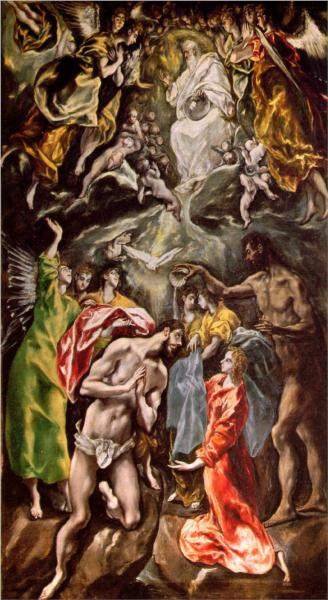

Jesus prayed that all who believed in Him would be one, just as He and the Father are one: that is, not just in a loose, spiritual affiliation, but completely, indivisibly One in Christ, of the very same substance and being. Paul tells us that we are one not only spiritually, but corporately:

I therefore beg you to lead a life worthy of the calling to which you have been called, eager to maintain the unity of the Spirit in the bond of peace. There is one body and one Spirit, just as you were called to the one hope that belongs to your call, one Lord, one faith, one baptism, one God and Father of us all, who is above all and through all and in all. … Speaking the truth in love, we are to grow up in every way into him who is the head, into Christ, from whom the whole body, joined and knit together by every joint with which it is supplied, when each part is working properly, makes bodily growth and upbuilds itself in love. (Ephesians 4:1, 3–6, 15–16)

These words go beyond exhortation: Paul describes the oneness of the Body not merely as a worthy model to strive for, but as a transcendent reality: There is One Body, One Spirit, One Lord. This oneness applies not only within each local body of believers, but across all believers, the entire, whole Body of Christ: the Epistle to the Ephesians is generally thought to have been a circular letter, circulated among a network of churches if not all churches. And lest there be any question that this Body of Christ to which Paul refers is to be understood as the Church, he tells elsewhere in the same letter:

[God] has put all things under His feet and has made Him the Head over all things for the Church, which is his Body, the fulness of Him who fills all in all.” (Ephesians 1:22–23)

And in other letters:

He is the Head of the Body, the Church; He is the beginning, the first-born from the dead, that in everything He might be pre-eminent. (Colossians 1:18)

One Church

The Greek word usually translated “church” in the New Testament is ἐκκλησία (ekklēsia). Most literally it means a calling out of people into a gathering or assembly or congregation; it was a standard word in Greek for a legislative assembly. I have heard Protestants seek to argue that the New Testament only understands the church in this general sense (the “little-c” church) and not as a single, corporate, universal body (big-C Church). But the verses already cited should leave little doubt to the fact that, just as we (even Protestants) today make a distinction in English between those two usages (the local church and the body of all believers), the New Testament authors and even Jesus Himself also saw a higher meaning of the word ἐκκλησία:

“On this Rock I will build My Church, and the powers of death shall not prevail against it.” (Matthew 16:18)

The use of that word ἐκκλησία had an even deeper meaning for a Greek Christian: ἐκκλησία was the common Greek translation the Hebrew קהל (qahal), that appeared in their editions of the Hebrew Old Testament, commonly translated in English as assembly — the assembly or congregation of the Israelite people. The ἐκκλησία, in the mind of a New Testament Christian, was not merely a local assembly of believers: the word evoked striking imagery of the Exodus, the calling out of God’s covenant people out of bondage and into promise.

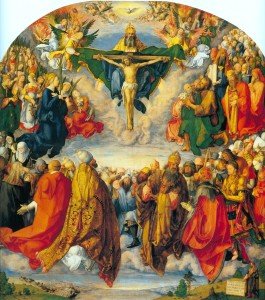

And so, Jesus’s words echo even more powerfully when He said, “I will build My Church”: not a building, not an institution, not a mere gathering of people, but a calling out of His people, a covenant people of His own. Here He laid its foundation, built on His apostles and prophets, destined to become a holy temple for the Lord (Ephesians 2:20). Here is the One Body of Christ, the Church.

Next time: “The Universal Church”: how the One Body of Christ proceeded whole and undivided; and how it came to be identified as the Catholic Church.