Today I’m struggling with a difficult post, so I thought I would give you something light.

Annedisa of Life, Christ & Me nominated me for the Liebster Blog Award some time ago. Liebster is German for “dearest.” And today I wanted to dedicate this award to you, mein liebster Leser (my dearest readers).

The award originated, my Google nosing* has revealed, as an award to honor up-and-coming bloggers with fewer than 200 readers. I honestly don’t really know how many readers I have, but I’m sure it’s fewer than 200. So, thank you, dear Annedisa. I don’t know whether my blog is “up and coming” or not, but I pray that wherever it may go, it speaks the truth in love.

* Thanks to Sopphey for in fact doing said nosing, which my nosing quickly happened upon. A splendid research into the history of the internets.

Annedisa’s blog is a lovely place always full with beauty and inspiration, and I enjoy it a lot. Check it out, if you haven’t!

Now I’m supposed to nominate eleven people — but I don’t really think I know eleven people. According to the original rules, as near as Sopphey could surmise, one was supposed to nominate 3–5 other bloggers with fewer than 3,000 200 readers†. I think I’ll go with that instead.

† Apparently the original specification was 3,000, but I think the change to 200 was a reasonable emendation. We little people need all the help we can get. Gadzooks, I wouldn’t even know what to do with 3,000 readers…

Annedisa also gave me some interview question, which I’ll answer. To add a little jazz, why don’t we do this: I’ll add a question to the list at the end (#12 below will be mine), for the next person to answer. Each person I pass this to will add a question, too — so the interview gets longer and longer, and more and more interesting. (I’ll go ahead and specify that if this really keeps going and the interview reaches 30 or so questions, someone needs to edit it down to a reasonable number again and pick only out the best questions.)

First, before this gets too long, let me nominate a few of my liebster bloggers (I’m not quite sure how to tell how many readers a blog has, but I think it’s safe to assume that most of us in our little Catholic WordPress circle are not Big Wheels):

-

Laura at Catholic Cravings, a dear fellow convert and fellow Medievalist‡, always blesses me with lovely, witty, astute, or thought-provoking observations on the Church and her road to it.

‡ I’m only part-Medievalist; but I’m sufficiently drawn in that direction that I claim it.

-

Roy at Becoming a Catholic, a dear candidate I discovered just a few days ago, walking the road of his conversion now, through the path of RCIA. I’m excited to be here to cheer him on!

-

1CatholicSalmon, who has been “liking” many of my posts lately, and I appreciate the encouragement more than you can know. Your blog is full of passion for the faith and strength in the face of rushing stream of modernity. May you go on rowing against the current!

Here are the instructions for reposting:

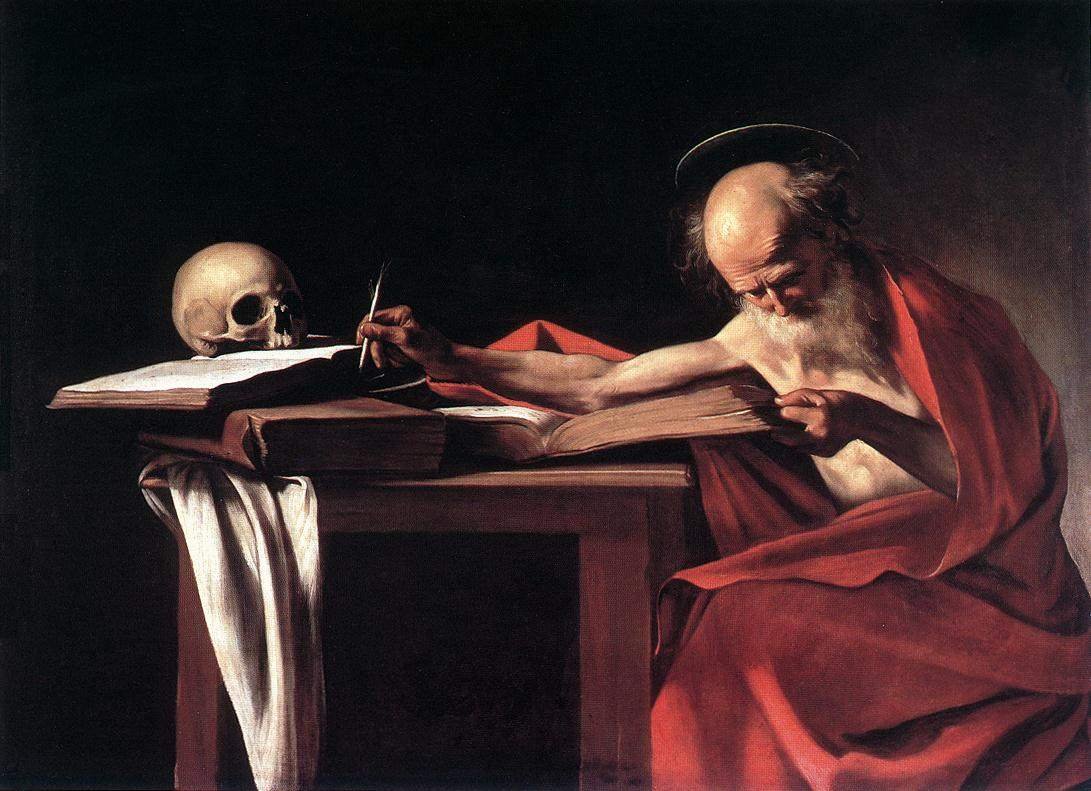

- Post the award image in a post of your own.

- Acknowledge who gave you the award (and link back to them).

- Choose 3–5 other bloggers who you think should be noticed more than they are and should have more readers, and pass the award on to them.

- Copy the interview questions below and answer them.

- Make up a question of your own and add it to the bottom, and answer it for yourself.

- Copy these instructions somewhere in the message to pass it on.

All right, without further ado, the questions:

1. A book that changed your life: The Book of Three by Lloyd Alexander. I’d like to tell that story sometime. But it was the first book that I recall really setting me on fire with a passion for reading and fantasy, when I was about seven years old.

2. Your favourite author/writer: Lloyd Alexander to this day remains one of my favorites; his books are still wonderfully entertaining to me. I recently dusted off my Dickens and I enjoy him a lot. I’ve been reading a lot of Catholic apologetics, etc., lately, especially Karl Keating, Jimmy Akin, Scott Hahn, and others. So I don’t really have a single favorite.

3. Pet and its name: My last pet was a betta fish called Ozymandias (Ozzy for short).

4. Craziest thing you have done: In due time.

5. My best friend: I have several, and they know who they are.

6. A childhood prank: At my tenth birthday party sleepover, one of my friends called the local radio station and pretended to be locked in the bathroom at the mall after hours, and asked if they could send somebody out to help him. Oddly, this was before cell phones were common — so I’m not sure how someone locked in the bathroom at the mall would have called a radio station. Ten-year-old logic. The DJ did mention my friend’s supposed predicament on the air. It was amusing at the time.

7. Favourite music artist: This changes frequently, and can fall into several categories:

- Favorite classical composers: Josquin des Prez, J.S. Bach, Orlande de Lassus, Tómas Luis de Victoria, Frédéric Chopin, William Byrd, Thomas Tallis, Guillaume Dufay — This could go on a while.

- Favorite classical artists: Oxford Camerata, Tallis Scholars, The Sixteen, Hillard Ensemble, Wolfgang Rübsam, John Eliot Gardiner with the Monteverdi Choir and the English Baroque Soloists, Sir Neville Marriner and the Academy of St Martin in the Fields — To name a few.

- Favorite contemporary artists: Rich Mullins, Danielle Rose (discovered her very recently and like her a lot), Matt Maher, Audrey Assad, David Crowder Band — To name a few.

So yes, it’s hard to narrow me down.

8. A place you would love to visit: I pine for Rome. I have a grand pilgrimage planned out, if I should ever have the time and money for it: A long time in Rome, then Assisi, then Florence, then Milan, then Pavia, then Turin (with many stops along the way), then up through Geneva to see Calvin’s stomping grounds — then either to France or Germany to see more saints; I haven’t really planned past Italy. But probably France, to pursue St. Bernard. Also, I’d love to go to England, especially London and Oxford and Cambridge, and York and Durham and Lindisfarne — and Scotland and Ireland, too. That sounds like another trip or four.

9. If you had just 5 minutes left to live what is the one thing I would do?: Ideally, I would be in bed surrounded by my family and my pastor receiving the last rites. But supposing I’m not — I’d fall on my knees and pray and confess whatever sin might be on my heart and throw myself upon the mercy of God.

10. Favourite sport: I agree with Annedisa: Does blogging count? Other than that, I would say American college football.

11. How do you define love?:

- Beloved, let us love one another, for love is from God, and whoever loves has been born of God and knows God. Anyone who does not love does not know God, because God is love. In this the love of God was made manifest among us, that God sent his only Son into the world, so that we might live through him. (1 John 4:7-9)

- Love does no wrong to a neighbor; therefore love is the fulfilling of the law. (Romans 13:10)

- Love is patient and kind; love does not envy or boast; it is not arrogant or rude. It does not insist on its own way; it is not irritable or resentful; it does not rejoice at wrongdoing, but rejoices with the truth. Love bears all things, believes all things, hopes all things, endures all things. (1 Corinthians 13:4-7)

12. Who’s your favo(u)rite saint? St. Paul, St. Gregory the Great, St. Bernard of Clairvaux, St. Thomas Aquinas, St. Francis of Assisi, St. Augustine of Hippo, St. Ambrose of Milan, St. Ignatius of Loyola, St. Bede the Venerable, St. Thérèse of Lisieux — So many precious people; you know you can’t nail me down.