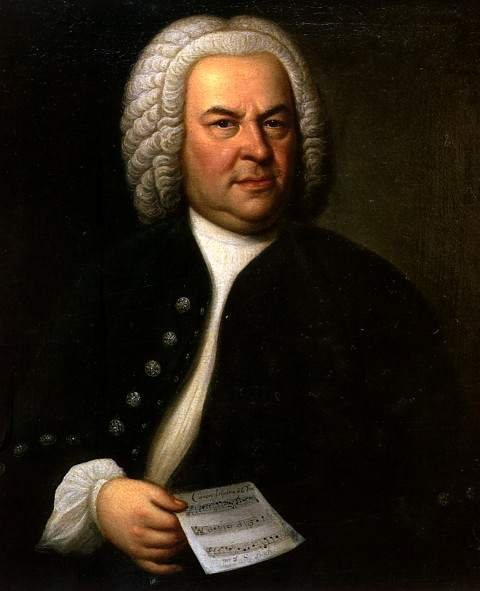

The Penance of St. Jerome (c. 1450), by Piero della Francesca. (WikiPaintings.org)

Today I discovered a new composer, and was immediately inspired to share him with my friends, and one thing led to another, and before I knew it, I’d translated the text of this overpoweringly beautiful and stirring motet. I thought it was worth sharing with you all.

I don’t know how many of you worldwide have access to Spotify; but I certainly hope many of you are able to hear this. Even if you can’t, I hope you enjoy the text. I highly recommend Spotify. With it I am able to explore and discover so much music, listen to whole records, all on a grad student’s budget.

This is from the CD TYE: Missa Euge Bone / MUNDY: Magnificat, from Naxos’s Early Music collection, performed by the Oxford Camerata under Jeremy Summerly (one of my favorite ensembles). This is the motet “Peccavimus cum patribus.”

Christopher Tye (c. 1505 – c. 1572) was an English composer and organist, who lived right in the thick of the English Reformation. He served as Doctor of Music at both Cambridge and Oxford, and as choirmaster and organist of Ely Cathedral. He apparently had Protestant leanings, but served faithfully through the reigns (and religious tumult) of Henry VIII, Edward VI, Mary I, and Elizabeth I. Later in life he took holy orders and served as Rector of Doddington, Cambridgeshire. This motet was composed, I suppose, under the Church of England, but I’m okay with that. It hit me especially powerfully in the penitent mood I’ve been in lately.

I’ll translate it a little bit by bit. I wasn’t happy with the English translation on ChoralWiki.

Peccavimus cum patribus nostris, iniuste egimus, iniquitatem fecimus. Tuæ tamen clementiæ spe animati ad te supplices confugimus, benignissime Jesu.

We have sinned as our fathers,

we have done unjustly, and committed iniquity.

Nonetheless driven by hope of your mercy

We flee to you in supplication,

Kindest Jesus.

Qui ut omnia potes ita omnibus te invocantibus vere præsto es. Respice itaque in nos infelices peccatores, bonitas immensa.

Who just as you are able to do all things

So to all who have prayed to you

You are truly present.

Look upon therefore us unhappy sinners,

O boundless goodness.

Respice in nos ingratissimos miseros, salus et misericordia publica; nam despecti ad omnipotentem venimus, vulnerati ad medicum currimus, deprecantes ut non secundum peccata nostra facias neque secundum iniquitates nostras retribuas nobis.

Look upon us most ungrateful wretches,

O salvation and mercy for all;

for we despicable ones into your omnipotence come,

Having been wounded we run to your healing [or to the Physician],

Praying that you do not do according to our sins

Neither according to our iniquities repay to us.

Quin potius misericordiæ tuæ antiquæ memor pristinam clementiam serva, ac mansuetudini adhibe incrementum qui tam longanimiter suspendisti ultionis gladium, ablue innumerositatem criminum, qui delectaris multitudine misericordiæ.

Rather remembering your compassion of old

Retain your former mercy,

And add increase to your gentleness

With such long-suffering having held back

The sword of vengeance,

Wash away the countlessness of our offenses,

You who are delighted by a multitude of mercy.

Ingere cordibus nostris tui sanctissimum amorem, peccati odium ac cœlestis patriæ ardens desiderium, quod magis ac magis crescere faciat tua omnipotens bonitas. Amen.

Pour into our hearts

Most holy love for you,

a hatred of sin,

and a burning desire for the heavenly kingdom,

Which by your omnipotent goodness

Make to grow more and more. Amen.