Today at Mass we celebrated the Feast of Corpus Christi, the Solemnity of the Most Holy Body and Blood of Christ. According to the Roman Missal, the actual date of the feast worldwide was last Thursday, the Thursday after Trinity Sunday; but in countries in which Corpus Christi is not a Holy Day of Obligation, …

Monthly Archives: June 2012

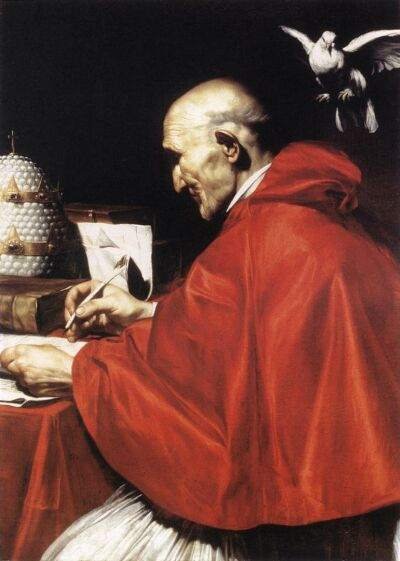

Pope Benedict XVI: A Father of Reconciliation

I presently have about four posts half-written; so forgive me if I begin another and for a moment indulge my inner fanboy and let loose a cheer for our pope. As I’ve been writing, there has been a longstanding conflict between Traditionalist Catholics and the Mother Church over the reforms of Vatican II, with the …

Continue reading “Pope Benedict XVI: A Father of Reconciliation”

New Every Morning

Remember my affliction and my wanderings, the wormwood and the gall! My soul continually remembers it and is bowed down within me. But this I call to mind, and therefore I have hope: The steadfast love of the LORD never ceases; his mercies never come to an end; they are new every morning; great is …

Paternalism, Employer Healthcare, and the HHS Mandate

Now, I did not want to get into politics in this blog. This blog is about healing division, not fomenting it. But my friend has got me upset about the issue of this HHS contraception mandate — she liberal and not understanding the Catholic position, I standing the ground of my Church. I wanted to …

Continue reading “Paternalism, Employer Healthcare, and the HHS Mandate”

What is a Saint? An Introduction for Protestants

It occurred to me the other morning in the shower (that’s where thoughts usually occur to me) that many Protestants might be troubled by the concept of saints and sainthood. I have heard Protestants say, “We don’t believe in saints.” I assure you that you do. Do you believe that there are people in Heaven? …

Continue reading “What is a Saint? An Introduction for Protestants”

St. Ignatius of Antioch on the Episcopacy

St. Ignatius, Bishop of Antioch, is one of our most vivid testimonies to the Early Church at the beginning of the second century. Arrested by the Roman Empire and sentenced to die, ca. A.D. 108, Ignatius wrote a series of letters to various churches while en route to his martyrdom in the arena at Rome. …

Continue reading “St. Ignatius of Antioch on the Episcopacy”

St. Boniface, Apostle of the Germans

Today is the Feast of St. Boniface (c. 7th century – 754), known as the Apostle of the Germans. Born with the name Wynfrith in the English kindgom of Wessex, he was renamed Boniface by Pope Gregory II, who commissioned him. He spent the last thirty years of his life as a missionary to the …

Why Protestants Should Care

So, I finally revealed my blog to my Facebook and Twitter friends. And a good many of them have followed me. Being a little more public has brought about a good bit of self-scrutiny: Am I relevant? Why should anybody want to read my blog? Why should Protestants, in particular, want to read my blog? …

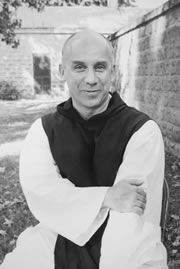

Thomas Merton on Saints

“It is a wonderful experience to discover a new saint. For God is greatly magnified and marvelous in each one of His saints: differently in each one. There are no two saints alike: but all of them are like God, like Him in a different and special way. In fact, if Adam had never fallen, …

Traditional Latin Mass

Last Sunday I attended my first traditional Latin Mass, at a local parish in Alabama while I was home visiting my parents. I had been meaning to check it out for a while. It was considerably different than what I’ve been used to; though I could still observe the basic form of the Mass. I …