The next post in my spiritual autobiography, and the conclusion(?) to my account of my struggle with Calvinism. I don’t know; maybe there will be more. I thought I would nudge a couple of Reformed friends in case they might be interested in my thoughts.

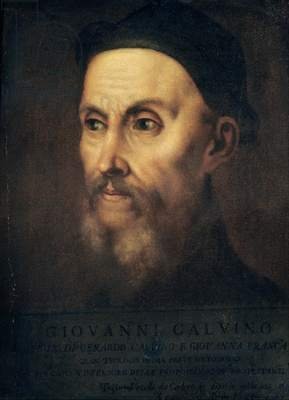

John Calvin, by Titian (This blog). I am thrilled to find this! I had no idea Titian painted Calvin! I love it when my favorite people cross paths!

I grew a lot as a person and as a Christian over the next few years — though still in short spurts, leaps, and sometimes stumbles. Over the last couple of years of my undergraduate career, I continued to have occasional flirtations with Calvinism. I hung out a few times with the fledgling RUF group on our campus, and attended the nondenominational Campus Crusade from time to time. But I struggled to feel that I fit in in any meaningful way. I visited the churches of several friends, but for reasons I don’t entirely understand looking back, I never settled down. I remained restless, insecure, and lonely.

In the spring of 2009, thanks be to God, I finally graduated. Over the next summer I flailed around uselessly looking for a job — and then, in one of the clearest manifestations of God’s providence that I’ve experienced, one came to me. One day my friend Gloria, who had been one of my dearest Christian friends in school and always an example to me of how to live one’s faith on campus, wrote on my Facebook wall. “Hey, Joseph, would you like to teach Greek at a Christian school?”

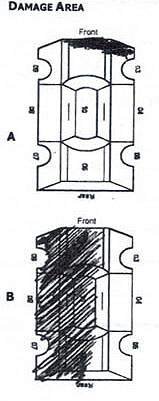

The Trivium.

Would I! I don’t think there could have been a more perfect job for me at that time if it had been custom-tailored. All through my undergraduate degree majoring in history, I had never given any serious thought to teaching or pursued teaching credentials — but to my great surprise and joy, I loved teaching more than anything I’d ever done. My year at Veritas Classical School, teaching history, Latin, Greek, and English grammar and vocabulary to grades seven through twelve, was a monumental landmark in my journey as a student, teacher, and Christian.

But more on that later. In coming to Veritas, my road brought me face to face with Calvinism.

That year also — not coincidentally — brought my walk with God closer than it had been in many years. Becoming a teacher, I felt an obligation to be a model and example spiritually, a mentor and tutor and protector as well. I prayed for my students before I even met them, and for myself that I would be worthy to stand before them. For the first time I read the whole New Testament with an eye to serious Bible study. For my thirtieth birthday I bought myself a new Bible — the Reformed-friendly ESV Study Bible. It was a time of great growth, and I felt that that — towards the Reformed — was the direction my faith was moving in.

As it turned out, the teacher I was replacing at Veritas was Megan, whom I had known years earlier as a member of the Society. (The pool of students in North Alabama trained in classical languages being small, this was not as big a coincidence as one might think.) She had recently had a baby and was leaving the school to be a mother. In my preparation that summer, I visited Megan’s home a couple of times to discuss curricula and planning. I was immediately impressed with the bookshelves of Megan and her husband: tome upon tome of Christian literature, particularly Calvin’s Institutes of the Christian Religion and other works of the Protestant Reformers. Could this be the intellectual foundation for my faith I’d been looking for? In talking with Megan, I was struck with a major emphasis of her teaching: history as a product of God’s sovereign will.

Veritas met in the building of a small Presbyterian church, and though at the forefront I’d been told that its reach was ecumenical — that I would have students of all different Christian traditions, and that no particular doctrinal position was expected of me — I learned very quickly that in its wider affiliations, Veritas was by and large Reformed. Toward the end of that summer, I attended a few days of workshops with the founders and leaders of the Veritas organization, at a large Presbyterian church in the Atlanta area.

(This is the Protestant Paul.)

It must have been the will of God that I would be reading Paul’s Epistle to the Romans that week, that specifically I would have arrived at Romans 8, 9, and 10. It wasn’t the first time in recent months that I’d read a passage of Scripture and had the nagging thought, What if the Calvinists are right? But the morning of the first day of workshops, I remember sitting in the beautiful garden of the home that had so graciously hosted us, reading those chapters. I remember the sinking feeling in my stomach, the rising panic, as the words seemed to confirm what I feared: “Has the potter no right over the clay, to make out of the same lump one vessel for honorable use and another for dishonorable use? What if God, desiring to show his wrath and to make known his power, has endured with much patience vessels of wrath prepared for destruction, in order to make known the riches of his glory for vessels of mercy, which he has prepared beforehand for glory?” (Romans 9:21–23). As I review my notes from that day (I kept a journal of my studies), I see that I made a surprisingly sharp exegesis then — which I can only credit to the Holy Spirit — as my mind reeled, clawing for an understanding of the passage that didn’t entail what it appeared to entail.

Over the next several days, as I was pondering these words, I found myself cast into an increasingly alien and uncomfortable situation: Veritas seemed to be an overwhelmingly Reformed phenomenon; every teacher whom I met was motivated by a Calvinistic outlook on faith, on education, and on history. Not only that — but I’d had up till that point only marginal contact with homeschooling and its mechanics and philosophy and culture; here I was thrown into the thick of a stirred pot in which everyone around me was a native and veteran and I was a lost foreigner, not knowing the terminology or concepts or attitudes. I heard lecture after lecture on incorporating a Christian worldview into education, and on that worldview’s inherent opposition to my whole, secular, academic educational background; how the whole world I had known, everything I’d been taught, was opposed to God and the Christian formation of young people. I wrote in my journal, amid my lecture notes and observations, God, I’m scared. God, I’m so terrified. A page or so later: More and more horrified. I can’t do this. I have absolutely nothing in common with these people. By the second day of this, I had all but resolved that I would resign my position at the first opportunity.

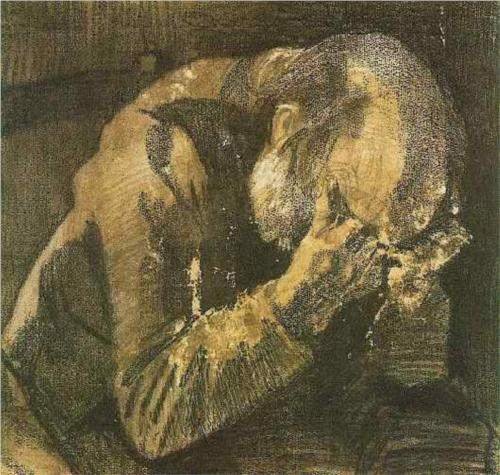

Man with His Head in His Hands (1882), by Vincent Van Gogh (WikiPaintings).

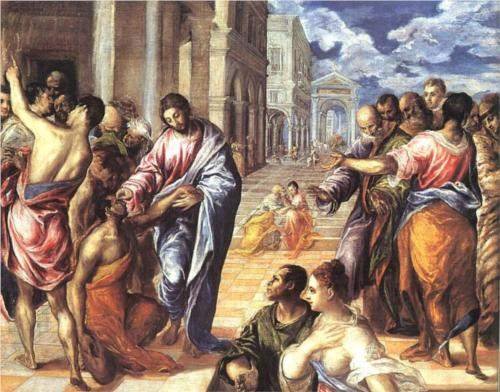

As these ideas worked through my head, and my reflections on Romans 9 continued to mushroom, I felt more and more alienated and alone: and this brewing storm soon blossomed into a full-brown crisis of faith. I began to seriously question whether I was even a Christian, if I even knew God at all. I remember sitting at a table there at that Presbyterian church, feeling more alone than I ever had, as the thoughts I’d been collecting finally coalesced: How could a loving God, a God who is love, create some flesh with no other purpose but to be damned? That rather than loving every creature, He only “endures with much patience” those “prepared for destruction” whom He doesn’t love at all, they existing only to “make known the riches of his glory for vessels of mercy,” those predestined for glory? How could a loving God deliberately and arbitrarily consign some on His creations to hell and save others, based on no merit or fault or choice or action of either? How could it be that many of the people around me, those whom I knew and loved — the very neighbors whom Jesus commanded us to love and serve, for whom he called us to give ourselves wholly — were “objects of wrath,” of mere tolerance in God’s eyes, and not of love? were hopelessly damned from the beginning of the universe? were bereft of any hope at all of salvation? The notions I had understood seemed to undermine the whole gospel of Christ as I knew it, to reject the essential dignity of all men and women, to call into question my entire moral fabric: if some men are not worthy even of the love of God, then why love the hurting or seek the lost? why feed the hungry or clothe the poor or bind up the brokenhearted? I began to understand, I thought, so much of what I saw in the world around me, why so few Christians in America seemed to care about the plight of the least of these: they are not “of us,” so they must be “vessels prepared for destruction.” As my horror reached it peak, I came to a conclusion: If this is the God I’m being asked to serve, then I want no part of that god.

Of course, so much of this was overreaction, and the fruit of everything else I was feeling at that time. These thoughts are not fair representations of the ideas or formulations of well-minded people of the Reformed faith. But I still feel truthfully that these are the logical implications and consequences of Reformed propositions.

As I went home after three days in Atlanta, I had come to a sense of peace. I don’t remember even acknowledging it consciously, but my conclusion had reduced to an absurdity: That couldn’t be the God I love and serve, therefore the premises from which I was proceeding must be false. The Calvinist understanding of Romans 9 must be mistaken: for it otherwise contradicts all the rest of Scripture and revelation. Over the coming weeks, I devoted myself more and more to Scripture study and prayer. I delved into Paul’s meaning and context, and at last came to understand; looking back, my notes upon my reading that first day were pretty dead on. It was an epoch in my journey: I never again seriously considered Calvinism as a valid theological option or the Reformed faith as a destination for my pilgrimage.

In the end, I stuck with Veritas. The director of our school was so very reassuring and so supportive. He restored my faith in my own calling and gifts, and in the promise of Veritas. He never asked me to teach in a way with which I wasn’t comfortable, and stood behind me through my entire year there. And the students and the parents and the environment made the most loving, nurturing, enriching educational experience I’d ever been a part of. I loved teaching more than I ever could have known, and loved my students with all my heart. I left convinced of the merits of classical education and homeschooling — but more on that next time.