William Tyndale

Some years ago, for an English history course as an undergrad, I wrote a paper on the Protestant Reformer and early translator of the Bible into English, William Tyndale. Now, I’ve always had a tendency to become absorbed with the subjects of my papers, and to find in them great heroes. Tyndale was no exception. I still admire the man for his erudition as a scholar, his creativity as a wordsmith, and his zeal for the Word of God. According to his most recent biographer David Daniell, at the time he translated the Bible in the early sixteenth century, he was perhaps one of the only men in all of England who knew the Hebrew language (Daniell, William Tyndale: A Biography, New Haven: Yale University Press, 1994, 287). I was convinced at the time I wrote the paper that the Catholic Church had become corrupted, and my paper reflects an anti-Catholic sentiment (my word, I didn’t realize how anti-Catholic until re-reading it just now). In retrospect, I realize I had absorbed a lot of that bias from Daniell, and from the indignation of Tyndale himself. Certainly, elements of the Church then were corrupt; the Church, without a doubt, needed to be reformed. I maintain that the Church was wrong to oppose the translation of the Bible, and wrong to persecute Tyndale, who first sought the Church’s permission to translate, for the sake of humanistic learning and ecclesiastical reform, and only violently opposed the Church after his work was rejected and condemned.

Already, in the five years since I wrote this paper, I can see how much my historical consciousness has deepened; how simplistic and one-sided my interpretations were. There was so much intricacy of ecclesiastical and state politics, personal zeal and personal fears, involved in the Reformation, and a lot of decisions handled very badly by a lot of people. I am so tempted to pursue more research into this. (::sigh:: I have far too many interests.) But all of this reminiscence is meant to preface the topic I really wanted to talk about: the Greek New Testament, and specifically the words ἐπίσκοπος, πρεσβύτερος, and διάκονος (bishop, elder, and deacon).

I was recently struck by a Mass reading of 1 Timothy 3, which gives requirements for church offices, in which ἐπίσκοπος (episkopos) was translated “bishop”: “A bishop must be irreproachable, married only once, temperate, self-controlled, decent, hospitable, able to teach, not a drunkard, not aggressive, but gentle, not contentious, not a lover of money” (1 Tim 3:2-3, New American Bible). I don’t know why I should have been surprised. Most recent evangelical Bible translations — the ones with which I’m most familiar in my personal study, the New International Version and recently the English Standard Version — translate ἐπίσκοπος “overseer”; but now I realize, in studying for this post, that the ubiquitous King James Version, John Wycliffe’s translation, and even Tyndale himself all translated the word “bishop.” Literally the Greek word is ἐπι + σκοπος — epi (upon, over) + skopos (looker, watcher; see the cognate “scope”) — one who watches over the church; an overseer — which is exactly what the bishop did, and does. By way of the Latin episcopus, it is the origin of our word bishop (still visible in our word episcopal). Anyway, if I were more literate in the tradition of early Protestant translation, I shouldn’t have been taken aback by the Catholic rendering. The ESV still gives “bishop” as an alternate reading in a footnote. The word “bishop” is so closely tied to the concept of “overseeing” that even Tyndale had no problem with it.

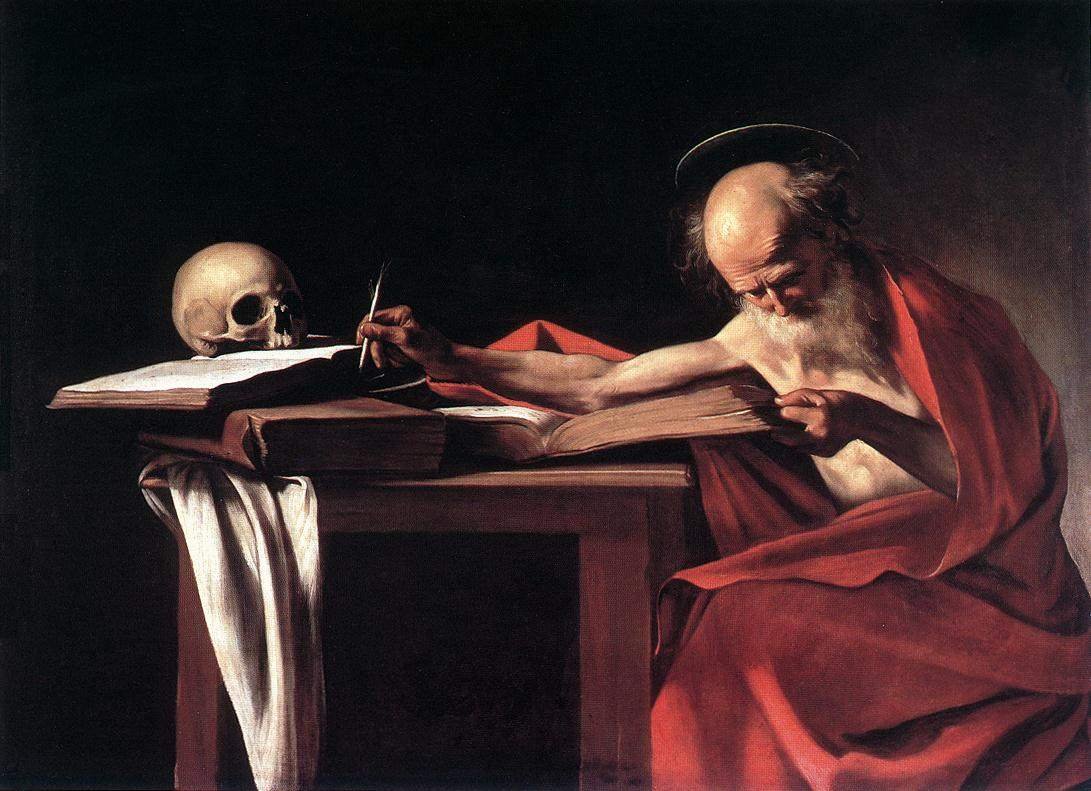

Where Tyndale got himself into hotter water was in the translation of πρεσβύτερος (presbyteros) as “senior.” Here, too, I needed to do more studying, for I’ve learned some things tonight. Traditionally, I argued in my Tyndale paper, the Catholic Church translated the word “priest.” At the time, I considered this quite scandalous, for I knew very well that the Greek word conveys nothing resembling priesthood, but merely an “elder” or “senior”; an older person. But I was perplexed to find, when I checked tonight, that the Douay-Rheims Bible, the first English translation of the Bible authorized by the Catholic Church (the New Testament was published 1582), also translates several instances of πρεσβύτερος in Greek as “ancient” (see 1 Pet 5:1, 2 John 1); so did Wycliffe. Both the Douay-Rheims translators and Wycliffe translated from the Latin Vulgate. So I went back to it. It seems the New Testament of the Vulgate is inconsistent in its translation of πρεσβύτερος into Latin — sometimes, such as the instances I just mentioned, it’s rendered senior (hence “elder” or “ancient”); other times, such as Titus 1:5 and James 5:14, it’s rendered presbyter. Perhaps this is evidence of the seams in St. Jerome’s translation. I’ve read that he didn’t actually spend much time in translating the New Testament, but simply revised an Old Latin translation. I would guess that senior is Jerome’s rendering, being the erudite Greek scholar that he was. Anyway, it’s in translating πρεσβύτερος as “elder” in all of these places (among other translation choices that seemed to call the sacraments into doubt) that Tyndale earned the disapprobation of the Church.

It bothered me that the Church translated πρεσβύτερος or presbyter as “priest” without any seeming reason. In fact, I always wondered — where does the office of priest in the Catholic Church even come from? It’s never mentioned in the New Testament, as far as I understood the Greek. It wasn’t until that Mass reading a few weeks ago that it hit me with a start. Presbyter and priest are cognate. The word priest in English in fact has its origin in the Latin presbyter. The OED confirmed this for me. Priest entered the Anglo-Saxon (Old English) language as early as the earliest extant documents in the eighth or ninth century (the Code of King Alfred is cited). The elders of the New Testament Church became what we know in the modern Church as priests.

This is already getting too long — but I’ll just say, in brief, that διάκονος (diakonos) literally means “agent, assistant, servant” — and nobody seems to have ever had any problem translating it “deacon.”

There’s considerable historical debate, however — and admittedly, this is not a historiography I’ve pursued, though I’d like to — over at what point the office of “overseer” in the early Church became the traditional, familiar, Catholic bishop; the single, chief ruler of a local church. The doctrine is referred to as the monarchical episcopacy or the monoepiscopacy. Liberal scholars (e.g. Bart Ehrman) have argued that it didn’t firmly develop until well into the second century. It appears that in the New Testament, the words ἐπίσκοπος (bishop/overseer) and πρεσβύτερος (elder/priest) are used interchangeably. For example, referring back to 1 Timothy 3, St. Paul gives the requirements for bishops and deacons, but makes no mention of elders. St. Peter, in 1 Peter 5:1, refers to himself as one among the elders of the Church, a “fellow elder.” But the Catholic Church holds that St. Peter was the first bishop of the Church in Rome, and by virtue of that, the first pope. What does it mean for that claim, if “bishops” and “elders” in the New Testament Church seem to be the same thing? Personally, I say not a thing. Even if the Church was slow to develop that there only needed to be one “bishop” in a local church, one “overseer” who was in charge — even if there was more than “overseer” in the beginning — and it’s not at all clear that this was the case — then certainly Peter, being the foremost Apostle (and the only Apostle, evidently, active in that office in Rome, since St. Paul never refers to himself as an “elder” or “overseer”), to whom Christ had entrusted the keys to the kingdom and on whom he said he would build his Church, was the foremost bishop, the one to whom everyone deferred, by virtue of his authority. The primacy and supremacy of Peter stands.

There’s considerable historical debate, however — and admittedly, this is not a historiography I’ve pursued, though I’d like to — over at what point the office of “overseer” in the early Church became the traditional, familiar, Catholic bishop; the single, chief ruler of a local church. The doctrine is referred to as the monarchical episcopacy or the monoepiscopacy. Liberal scholars (e.g. Bart Ehrman) have argued that it didn’t firmly develop until well into the second century. It appears that in the New Testament, the words ἐπίσκοπος (bishop/overseer) and πρεσβύτερος (elder/priest) are used interchangeably. For example, referring back to 1 Timothy 3, St. Paul gives the requirements for bishops and deacons, but makes no mention of elders. St. Peter, in 1 Peter 5:1, refers to himself as one among the elders of the Church, a “fellow elder.” But the Catholic Church holds that St. Peter was the first bishop of the Church in Rome, and by virtue of that, the first pope. What does it mean for that claim, if “bishops” and “elders” in the New Testament Church seem to be the same thing? Personally, I say not a thing. Even if the Church was slow to develop that there only needed to be one “bishop” in a local church, one “overseer” who was in charge — even if there was more than “overseer” in the beginning — and it’s not at all clear that this was the case — then certainly Peter, being the foremost Apostle (and the only Apostle, evidently, active in that office in Rome, since St. Paul never refers to himself as an “elder” or “overseer”), to whom Christ had entrusted the keys to the kingdom and on whom he said he would build his Church, was the foremost bishop, the one to whom everyone deferred, by virtue of his authority. The primacy and supremacy of Peter stands.

In any case, though Bart Ehrman notes that at the time of 1 Clement (the First Epistle of Clement to the Corinthians, among the writings of the Apostolic Fathers), dated ca. A.D. 95-96, the monoepiscopacy wasn’t in place yet, and the terms “bishop” and “elder” continued to be used synonymously (Ehrman, ed., The Apostolic Fathers Vol. 1, Loeb Classical Library, Cambridge: Harvard UP, 2003, 22, noting 1 Clement 44), the epistles of St. Ignatius of Antioch, written just a few years later, between A.D. 98 and 117, firmly argue to the churches that received them that they should submit to their one bishop. By the beginning of the second century, if not before, the monoepiscopacy was coming into being. Presbyters were becoming what we know as priests. And the Church we know has descended from these men.