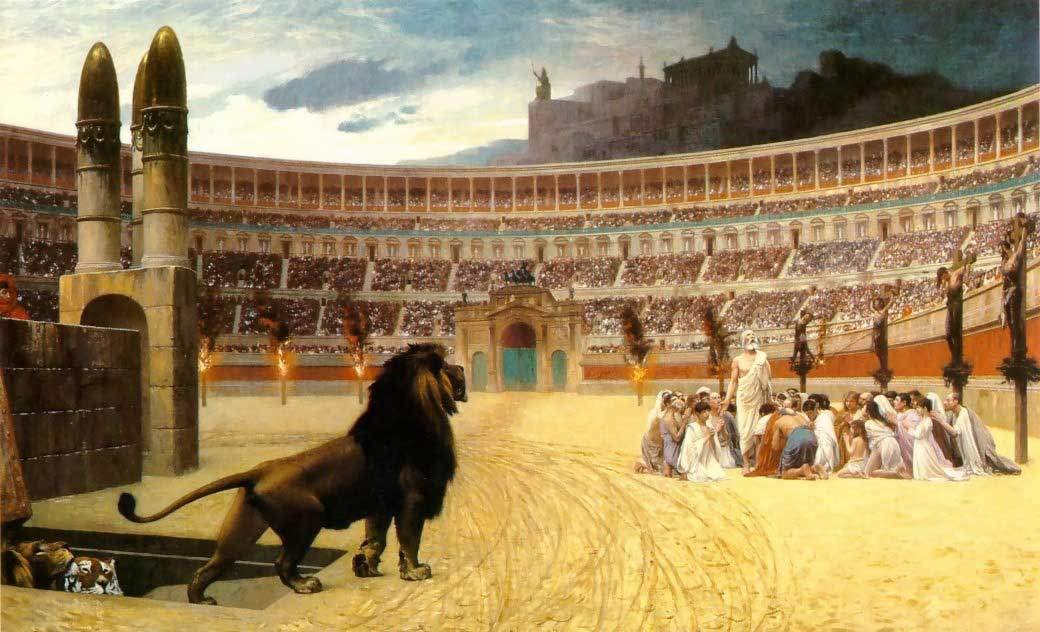

Today is the feast day of St. Augustine, and though I have a lot of other things on my plate today, I thought it was an opportune time to make a first post in a matter that’s been boiling over in my head for a while. A couple of months ago I finished reading Alister McGrath’s Iustitia Dei: A History of the Christian Doctrine of Justification, a compelling and masterful work on that subject of such importance to the ongoing schism of the Protestant Reformation. In only a few hundred pages, McGrath surveys the whole Western theological tradition, cutting to the crux of major theologians and theologies from Augustine to Barth, and digging to the root of the disagreements and controversies. He shows a thorough command of the literature, especially into the voluminous corpus of St. Augustine, but also likewise into a number of important medieval thinkers, and into Luther and Calvin. (In the second edition which I read, he was even so hardcore as to leave primary source quotations in their original Greek, Latin, and German. In the third edition, more accessible to a general audience, he does translate these quotations — which, brushing aside the vestiges of my academic snobbery, is a welcome relief. Reading it the first time was a world of brainhurt!)

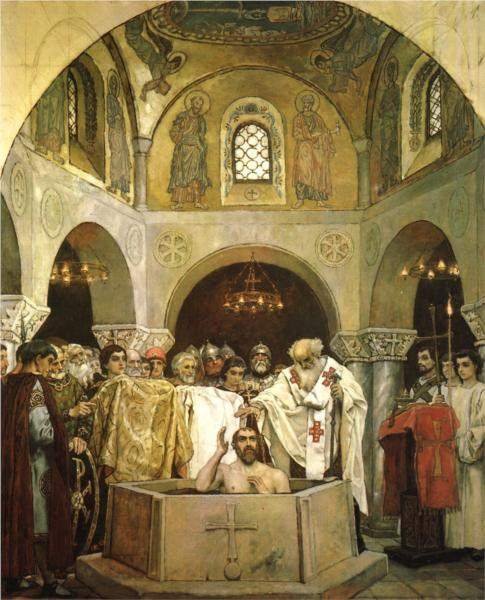

McGrath is an honest and insightful historian, and so thoroughly versed in his material that this work should be considered the authority on the matter. I would like to give a full review — or even share a series of posts on some of the important points — but I think that will have to wait a little while. For today, I would like to share a few quotes from McGrath’s chapter on Augustine, whom he calls the “fountainhead” of the doctrine of justification, the first western theologian to devote his substantial energies to it, and the one in whose wake all later theologians would follow. In McGrath’s words, “All medieval theology is ‘Augustinian’, to a greater or lesser extent,” and even the Protestant Reformers attempted to stake a claim to an Augustinian heritage. But I felt vindicated as a Catholic in discovering that, by the judgment of even a Protestant scholar, Augustine’s theology is thoroughly catholic, and that the teachings of the Catholic Church on justification have been, have never ceased to be, and are still today, essentially Augustinian.

Giving only a few quotations will be difficult — since I have most of the chapter highlighted! — but I will pick out a few passages highlighted in red: those that I found to be the most piercing and profound.

In rejecting the teachings of Pelagianism — that man has the power to save himself by his own free will apart from grace — Augustine did not reject that man has free will. He was careful to distinguish between liberum arbitrium (free will) and liberum arbitrium captivatum (free will taken captive or enslaved by sin). It is only by grace that our will is freed to pursue God. “Grace, far from abolishing the free will, actually establishes it.”

In a firm rejection of the Calvinistic notion of “monergism,” and in full accord with Catholic teaching, McGrath states:

For Augustine, the human liberum arbitrium captivatum is incapable of desiring or attaining justification. How, then, does faith, the fulcrum about which justification takes place, arise in the individual? According to Augustine, the act of faith is itself a divine gift, in which God acts upon the rational soul in such a way that it comes to believe. Whether this action on the will leads to its subsequent assent to justification is a matter for humanity, rather than for God. ‘The one who created you without you will not justify you without you’ (‘Qui fecit te sine te, non te iustificat sine te’). Although God is the origin of the gift which humans are able to receive and possess, the acts of receiving and possessing themselves can be said to be the humans’.

McGrath continues:

To meet what he regarded as Pelagian evasions, Augustine drew a distinction between operative and co-operative grace. God operates to initiate humanity’s justification, in that humans are given a will capable of desiring good, and subsequently co-operate with that good will to perform good works, to bring that justification to perfection. God operates upon the bad desires of the liberum arbitrium captivatum to allow it to will good, and subsequently co-operates with the liberum arbitrium liberatum to actualise that good will in a good action.

I wonder where he ever got an idea like that?

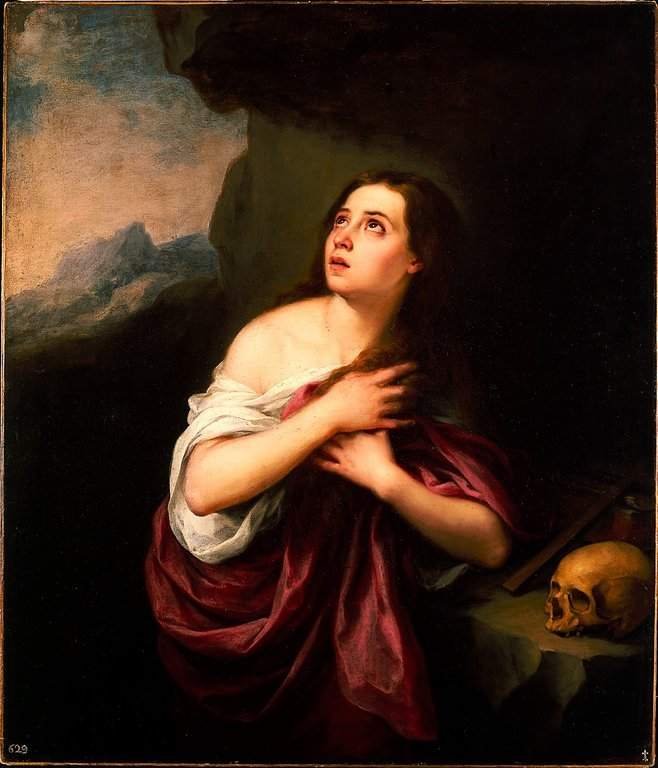

Regarding Augustine and the doctrine of merit, McGrath quotes:

The classic Augustinian statement on the relation between eternal life, merit and grace is the celebrated dictum of Epistle 194: ‘When God crowns our merits, he crowns nothing but his own gifts.’

Concerning the “righteousness of God,” the namesake of the book, he writes:

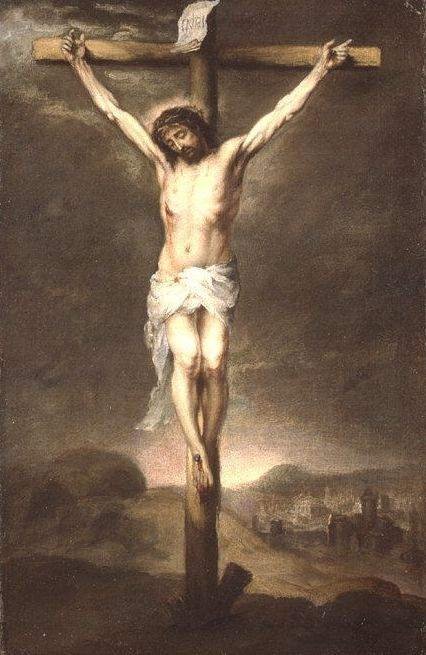

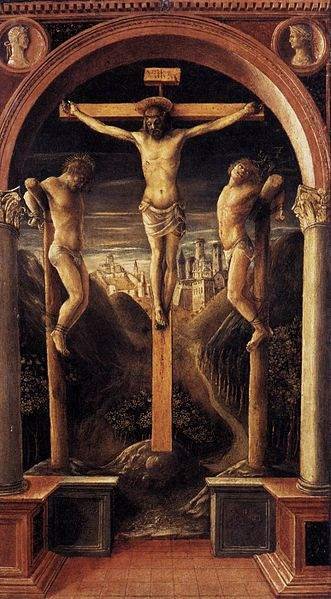

Central to Augustine’s doctrine of justification is his understanding of the ‘righteousness of God’, iustitia Dei. The righteousness of God is not that righteousness by which he is himself righteous, but that by which he justifies sinners. The righteousness of God, veiled in the Old Testament and revealed in the New, and supremely in Jesus Christ, is so called because, by bestowing it upon humans, God make them righteous.

Finally, dealing a deathblow to any inkling that Augustine ever held a doctrine of “justification by faith alone”:

Regeneration is itself the work of the Holy Spirit. The love of God is shed abroad in our hearts by the Holy Spirit, which is given to us in justification. The appropriation of the divine love to the person of the Holy Spirit may be regarded as one of the most profound aspects of Augustine’s doctrine of the Trinity. Amare Deum, Dei donum est. [To love God is the gift of God.] The Holy Spirit enables humans to be inflamed with the love of God and the love of neighbours — indeed, the Holy Spirit is love. Faith can exist without love, on the basis of Augustine’s strongly intellectualist concept of faith, but is of no value in the sight of God. God’s other gifts, such as faith and hope, cannot bring us to God unless they are accompanied or preceded by love. The motif of amor Dei [the love of God] dominates Augustine’s theology of justification, just as that of sola fide would dominate that of one of his later interpreters. Faith without love is of no value.

But what of Paul’s references to justification by faith?

So how does Augustine understand those passages in the Pauline corpus which speak of justification by faith (e.g., Romans 5:1)? This question brings us to the classic Augustinian concept of ‘faith working through love’, fides quae per dilectionem operatur, which would dominate western Christian thinking on the nature of justifying faith for the next thousand years. The process by which Augustine arrives at this understanding of the nature of justifying faith illustrates his desire to do justice to the total biblical view on the matter, rather than a few isolated Pauline gobbets.

Ouch!

In summation to this point:

It is unacceptable to summarise Augustine’s doctrine of justification as sola fide iustificamur [we are justified by faith alone] — if any such summary is acceptable, it is sola caritate iustificamur [we are justified by love alone]. For Augustine, it is love, rather than faith, which is the power which brings about the conversion of people. Just as cupiditas is the root of all evil, so caritas is the root of all good. The personal union of individuals with the Godhead, which forms the basis of their justification, is brought about by love, and not by faith.

The word “love” is used in Scripture more than 500 times, versus about forty times the words “justifiction” or “to justify” are used. It is no accident that the greatest commandments, according to Jesus, are to “love the Lord your God with all your heart, mind, soul, and strength” and to “love your neighbor as yourself” (Luke 10:27); or that, in Paul’s teachings, “Love is the fulfilling of the law” (Romans 13:10). I think that in focusing so heavily on a “few isolated gobbets” of Paul, and fixating on the doctrine of justification to the detriment of the rest of Scripture, the Protestant Reformers may have missed the boat entirely.

(And this only gets me about halfway through the chapter! I will have to pick up the rest next time.)