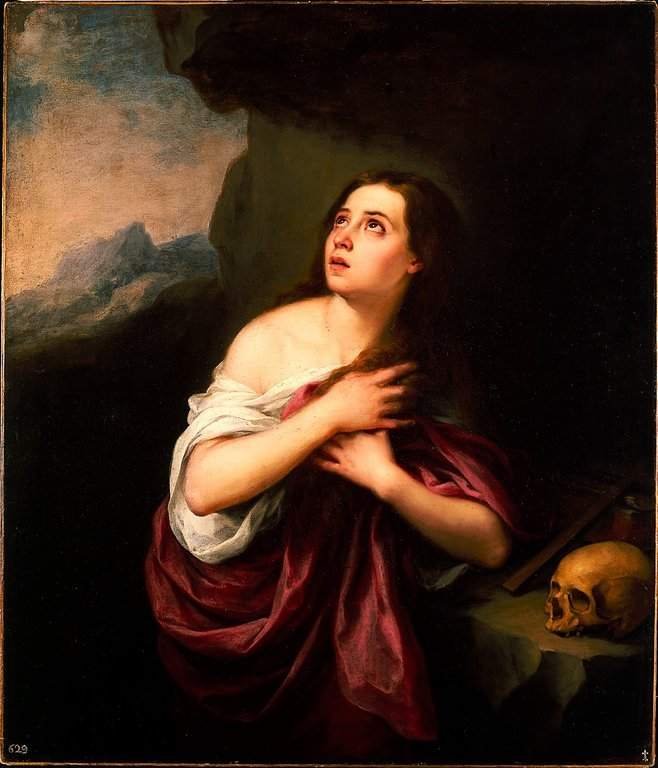

Penitent Magdalene (1665), by Bartolomé Esteban Murillo (WikiPaintings)

As always, this turned out to be longer and more involved than I intended. So consider this part 1 in a series on Indulgences. And no, I haven’t forgotten about Baptism.

The other day Pope Francis granted a plenary indulgence to those devoted faithful who would follow his tweets or other coverage of the World Youth Day events in Brazil — to the bemusement of the global media and the consternation and ridicule of many Protestants. It seems, to some, a crass abuse of spiritual authority for the motive of getting more “followers” — authority he doesn’t have anyway, according to Protestants: a sham and a mockery of the Gospel, I have heard. Rather than being embarrassed at a faux pas before the media and the world, I praise God for a Holy Father who humbly offers forth the truth despite ridicule. I thought this would be an ideal opportunity to share a bit about the truth of indulgences, what they really mean, and why they are important today.

Now, indulgences are a rather complicated and confusing doctrine: complicated even more by the negative baggage they carry from the age of the Protestant Reformation. When Protestant ears hear “indulgence,” they automatically think “abuse” and “corruption.” I know; I grew up a Protestant, and thought that even though I was never particularly anti-Catholic. But in truth, the doctrine of indulgences is built upon basic and biblical principles, and has roots as ancient as the Church, sprouting from the seeds of the Apostles.

I made a post almost exactly a year ago trying valiantly to tackle this difficult topic — bless my baby Catholic heart. I am still a baby Catholic, but I have grown so much in the past year and think I could do much better than that, if I had time. I think you can still learn something about what indulgences are and what they are not from that post.

Let me start with those basic building blocks: We all know that we sin (1 John 1:5–10). Everybody, including Protestants, thinks about the eternal punishment due for our sins (Romans 6:23) that we would face if not for the forgiveness of God by the atoning death of Jesus (1 John 2:2). But what Protestants tend not to talk about — but surely recognize — is that our sins have consequences in this life, on us and on those around us, on the ones we hurt by our sin and also the ones who hurt with us because of our sin. Sin is misery (Psalm 25:18, Romans 2:9).

St. Peter Penitent (c. 1600), by Guido Reni. (WikiPaintings.org)

We serve a just God, and sin being misery is how He made the world. When we sin, we suffer our just deserts of that misery, even after God forgives us. And suffering through that pain is part of God’s process of healing and teaching: to bring us to true repentance and contrition for our wrong, that we can be healed from the hurt, and purified from the stain, and that we can learn and grow and not fall again. Remember, for the classic example, King David — who, even after he was forgiven by God (2 Samuel 12:13), still had a heavy price to pay in misery (Psalm 51, etc.). This is what the Church calls the temporal punishment due for sin, and it is clearly something separate from the guilt of sin from which Christ redeems for us by His grace. And this is the whole idea of penance: the priests of the Church, having received the authority of the apostles to bind and loose (Matthew 18:18) and to remit and retain sin (John 20:22–23), have the authority to impose penance on us as a means to work through that temporal punishment. Penance is not an actual punishment so much as it is a remedy: Jesus is our spiritual physician, and through the priest, He gives us a prescription for the healing of our souls.

Jesus Returning the Keys to Peter (1820), by Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres (WikiPaintings.org)

And the basic idea of indulgences is this: Because the Church imposed those penalties, she has the power to remit them. What is bound on earth is bound is heaven, and what is loosed on earth is loosed in heaven — and these penances, designed for our spiritual healing and growth in grace, can be released, if it seems they have served their purpose. By analogy, the penance is a big, unwieldy cast, designed to set our broken bones; and when it seems our bones have healed, the doctor removes the cast. And that’s all, in the most basic sense, an indulgence is. From the Latin indulgentia, it means literally a remission or release. We see in Scripture, for example, the case of a sinner in the Corinthian church, upon whom “punishment by the majority” had been placed — presumably excommunication (1 Corinthians 5:2) or other penitential acts. And, deciding that the sinner had had enough, that he had been restored, Paul remits the punishment:

For such a one this punishment by the majority is enough; so you should rather turn to forgive and comfort him, or he may be overwhelmed by excessive sorrow. So I beg you to reaffirm your love for him. For this is why I wrote, that I might test you and know whether you are obedient in everything. Any one whom you forgive, I also forgive. What I have forgiven, if I have forgiven anything, has been for your sake in the presence of Christ [ἐν προσώπῳ Χριστοῦ, lit. in the face of Christ — Latin in persona Christi], to keep Satan from gaining the advantage over us; for we are not ignorant of his designs. (2 Corinthians 2:6–11)

The doctrine developed a little bit from this before it came to resemble what we call indulgences today, but this is the start: the Church’s remission of a penance — a rehabilitation for the hurts of sin, for a sin already forgiven — for someone who, in the judgment of the Church, has risen above the sin, by God’s grace. Penance is the Church’s version of spiritual rehab: when you’re broken, you have to endure some painful exercises before you can properly heal. And when the doctor decides you no longer need it, you’re free to go — and that’s an indulgence.

More in Part 2: Indulgences: Gift of the martyrs