Hi, I’m back in school now and still trying to organize my time. I haven’t had much of a chance to sit down and write, especially not about any large subjects; but in today’s Mass readings, an idea hit me forcefully that I think I might be able to comment on quickly. This will be an exercise in brevity, both of length and time.

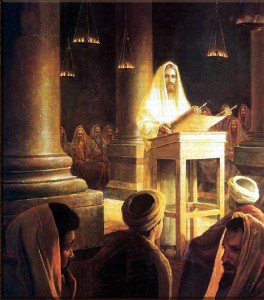

I’ve always been struck by today’s Gospel reading (Mark 1:21–28): “The people were astonished at His teaching, for He taught them as one having authority.” Jesus was something completely different, something no one had ever seen before. Not since Moses himself, the codifier of the Law, had anyone spoken with such authority on the Law and the mind of God toward human behavior.

He stood in vivid contrast to the so-called authorities of the day, the Pharisees and Sadducees, the scribes and scholars of the Law. The only authority they ever offered was their own, as they disputed endlessly on the interpretation and application of the Law. They had sola scriptura: Scripture alone, the divine and authoritative Word of God, in the Law and the Prophets — and yet they did not have authority. For all their scholastic eminence and merits, they could offer only disagreement and division. Jesus did not come to give God’s people more of the same: another holy book or another teacher or even another prophet. He came to give them something radically new and different.

Jesus spoke with authority, such that there was no question, dispute, or ambiguity about what He meant. And he gave that same authority to His Apostles (Matthew 10:1, 40; Luke 10:16), to speak and to teach with His voice. And the Apostles gave their successors, the bishops, that same authority to teach (1 Timothy 4:11, etc.). And this is the same authority with which the Magisterium of the Church teaches today.

By contrast, see the state of teaching in the Protestant churches. When a preacher stands up to teach, he may speak with self-assurance; he may speak from the divine, authoritative Word of God; but he gives an interpretation; he does not speak with authority. In the Protestant world, there are only endless disputes concerning doctrine and interpretation. Sola scriptura — “Scripture alone” — without prophets, without a Christ — is all the Jewish people had before Jesus came. And He came to deliver us from that chaos and confusion, as surely as He came to deliver us from sin and death. The Protestant proposition seeks to return the Church to that: to deny and reject the very authority that made Jesus Christ’s revelation so radical and so powerful a revolution.