One of the most frequent charges I hear, when I point out the inherent chaos and disunity of Protestantism, is that “there is a lot of disagreement in the Catholic Church, too” — that somehow disagreements within the Catholic Church are equivalent to, or excuse, the fundamental doctrinal disagreements between diverse Protestant churches. In particular, opponents point out the large number of self-identified Catholics who practice artificial birth control or support abortion or same-sex marriage in contradiction to the teachings of the Church. My response is that there is a fundamental distinction between what the Church teaches — the one, consistent, unified and unambiguous teaching of the Church’s infallible Magisterium, as summarized in the Catechism of the Catholic Church — and what individual Catholics do and believe, the doings and failings of fallible people who may make mistakes and stray from the flock. Even if a large number of people should disagree, sin, or fall away from the truth, it does not change the truth that is taught or besmirch the teacher.

One of the most frequent charges I hear, when I point out the inherent chaos and disunity of Protestantism, is that “there is a lot of disagreement in the Catholic Church, too” — that somehow disagreements within the Catholic Church are equivalent to, or excuse, the fundamental doctrinal disagreements between diverse Protestant churches. In particular, opponents point out the large number of self-identified Catholics who practice artificial birth control or support abortion or same-sex marriage in contradiction to the teachings of the Church. My response is that there is a fundamental distinction between what the Church teaches — the one, consistent, unified and unambiguous teaching of the Church’s infallible Magisterium, as summarized in the Catechism of the Catholic Church — and what individual Catholics do and believe, the doings and failings of fallible people who may make mistakes and stray from the flock. Even if a large number of people should disagree, sin, or fall away from the truth, it does not change the truth that is taught or besmirch the teacher.

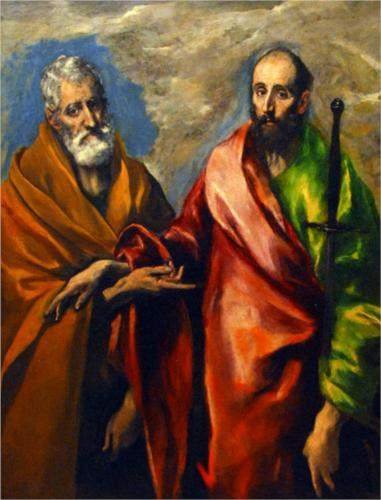

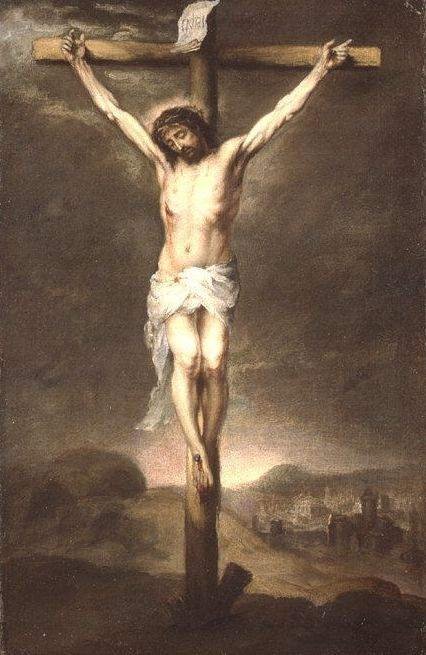

The leading charge of the Protestant Reformation is that the Church had fallen away from a true understanding of the doctrine of justification as taught by St. Paul — that in contrast to the claims of Protestants, that justification is “by faith alone” (sola fide), the Catholic Church taught a doctrine of “works’ righteousness,” that somehow by our own working we can deserve or earn our own salvation. I have written a lot on justification and presented frequently here that this is not what the Catholic Church actually teaches. I have attempted to make the distinction before, and I have a new post in the docket in which I want to explore the point further: Catholics do believe in justification by faith and not our own efforts; where Protestants disagree is only in proposing that no human response at all is necessary.

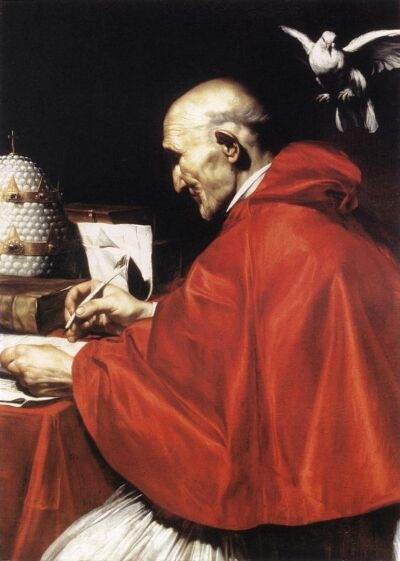

Antonio Rodríguez, Saint Augustine (Wikimedia).

It’s clear from history that the Church has never actually taught a doctrine of “works’ righteousness,” the thesis that man, by his own effort, can in any way save himself. This is the heresy of Pelagianism, which the Catholic Church has always and consistently condemned. Saint Augustine, Saint Thomas Aquinas, and other monuments of Catholic theology consistently maintain that justification is only by the grace of God through faith and not human effort. Alister McGrath, in his brilliant Iustitia Dei: A History of the Doctrine of Justification, demonstrates convincingly that even throughout the rigorous scholastic debates of the Middle Ages, the teachers of the Church never abandoned the orthodoxy that no effort or merit of man can save him apart from God’s grace. The teaching of the Church, then, I’ve believed, was always consistent in teaching justification by God’s grace alone: what the Protestant Reformers charged and challenged was nothing new and nothing needed.

A blind spot

Gentile da Fabriano, Thomas Aquinas, detail from Valle Romita polyptych, c. 1400 (Wikimedia).

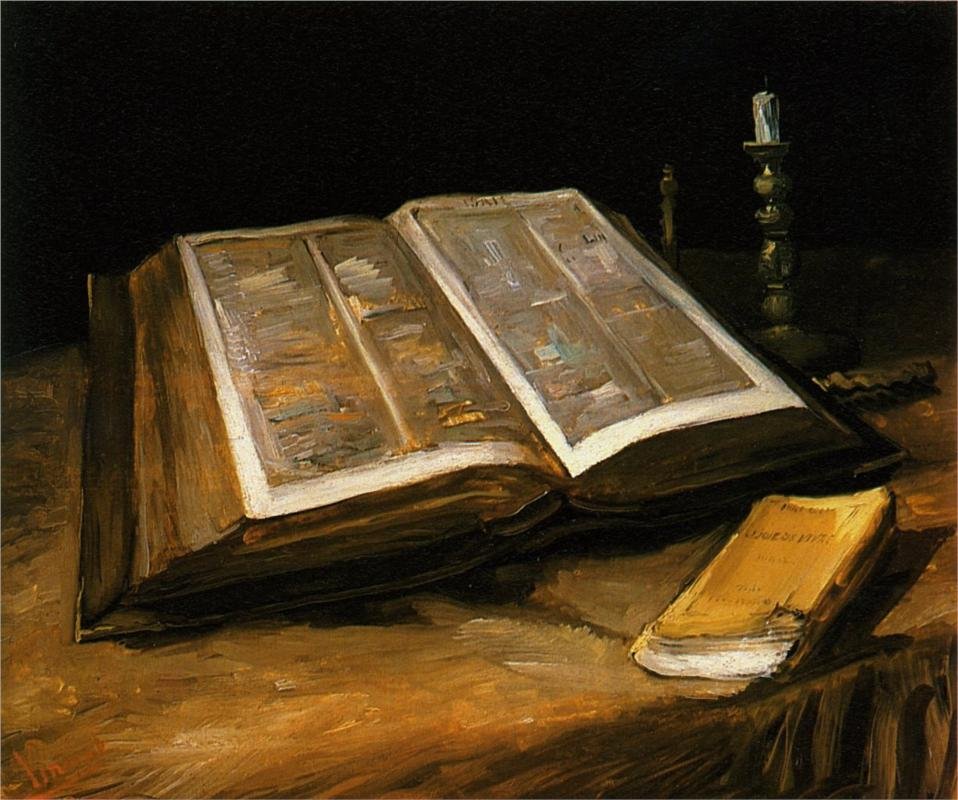

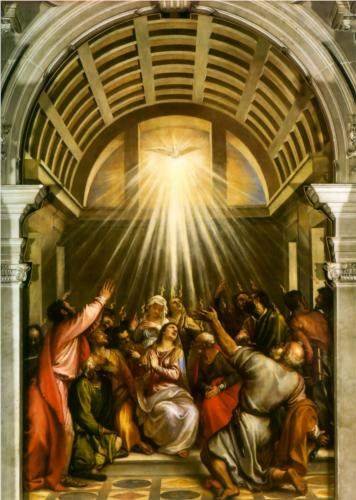

In my recent forays into the history of the Reformation era, I’ve come to realize that in this I may have had a blind spot. Despite the Church’s consistent condemnation of Pelagianism (“works’ righteousness”); despite the clear teachings of Augustine and Thomas and other theological lights; the situation among the Catholic faithful and even many clergy in the late Middle Ages and early modern era prior to the Reformation may have been much like the situation today — with many believing something that wasn’t true, something that was contrary to the actual teachings of the Church. And this idea of the “actual teachings of the Church”: to presume the kind of monolithic unity that we have today, to be able to point at a single compendium of doctrine, the Catechism, and say, “This is the one, consistent teaching of the Catholic Church” — may be projecting an anachronism onto that era. There was no such book in the sixteenth century; there were few printed books at all, at the dawn of the age of printing, and the vast majority of the faithful were illiterate. The “one, consistent teaching of the Catholic Church” was scattered among myriad tomes, among the writings of numerous Church Fathers and the canons of numerous councils; and though it was one and consistent, it was not digestible in a form that any but the most learned academic could grasp. In practice, the actual teaching of the Catholic Church was what individual bishops and priests actually taught the faithful, and the truth is, in very many cases this was pretty shoddy.

John Calvin, by Titian (16th century) (Wikimedia).

For Protestants, the doctrine of justification is the very core of the Gospel, the fundamental essence of the truth, the sine qua non of salvation. This emphasis on justification may be myopic: Sacred Scripture devotes only a few words in a few passages to the idea of justification — much more pervasive ideas being the love and mercy and grace of God. Prior to Augustine in combating Pelagianism, no Christian author paid much attention to the doctrine of justification; in him, both Catholics and Protestants find the foundations of their doctrines. In Eastern Christianity, justification has never been a major focus, let alone the cornerstone of the Gospel. In the West, between the times of Augustine and the Council of Trent, the mechanics of justification were mostly a subject for scholastic exposition and debate, not “the doctrine by which the Church stands or falls.” So I think Protestants too have something of a blind spot in this regard.

But I concede that a lack of emphasis on justification and grace by the teachers of the faithful in the early modern era may have led to poor understandings by many about something that is crucial: how we can have a relationship with God, and how we can be saved. When Protestant preachers arrived on the scene in the sixteenth century, in many cases the idea of justification by faith alone caught on like wildfire, to those who felt they had been striving in themselves for salvation. Even if this belief in human effort leading to salvation was an incorrect understanding of what was in fact the true and orthodox Christian doctrine, it was the failure of the Church, in her individual pastors, to teach that truth. As much as we may deplore the breakdown of Christian unity that followed in their wake, in this even Catholics owe the Protestant Reformers a debt of gratitude, in returning the focus of Christian teaching to the grace of God.

The failure of the papacy?

I recently read a review of Brad S. Gregory’s book The Unintended Reformation by Reformed author Carl Trueman. In Gregory’s book, he argues that many of the foibles of modernity, in secularism and postmodernism, were the unintended fruits of the Protestant Reformation’s denial of authority, and the resulting diversity of Protestant interpretations of Scripture and inability to affirm one, unified truth. Trueman’s response is essentially, “That may be so, but what you offer is even worse.” “Perspicuity [the belief that the Scriptures themselves teach a single, clear truth] was, after all,” Trueman writes, “a response to a position that had proved to be a failure: the Papacy.”

Alexander VI (Cesare Borgia), one of the more notorious Renaissance popes. (Wikimedia)

I was taken aback to read this. The papacy — a failure? Honestly, in all my years, even as a Protestant, I don’t think such a thought ever crossed my mind, that the institution of the papacy was a failure. Trueman presents several respects in which he thinks the papacy was a failure: the medieval papacy was corrupt and caught up in politics and worldiness; the Western Schism of the papacy was such a mess that it took several councils just to sort out who the pope was; the early modern papacy failed to reform the Church with due speed and diligence following the Fifth Lateran Council even when many corruptions and failures were known. Yes, these things are all true. I would add my own: many popes of the medieval and early modern papacy failed to make the pastoral care of souls their chief concern; failed to make teaching the doctrines of the faith the heart of their work; failed to appoint bishops who would do the same. There was a breakdown, and yes, reform was desperately needed. But was the breakdown, the failure, in the office of the papacy, or in the men who held it, who allowed the world to pull their focus from what it should be?

Perhaps the most central concern is whether the papacy is a failure for what we maintain Christ intended it to be: as a guarantor of the truth and unity and orthodoxy of the faith. Yes, some men who held the office of the papacy were failures in some respects: they failed to be “good Christians,” perhaps even good pastors; they failed to keep the heart of the gospel, the salvation of souls, at the center of their concerns. Perhaps they even failed as teachers, in that they could have taught the truth, and overseen the teaching of the bishops, with much better clarity and focus and consistency. But we look to the papacy as the final safeguard between orthodoxy and heterodoxy, the one to whom all other bishops must guide in teaching the truth, to ensure that error is not taught. In this respect, the only way that the institution of the papacy could be a failure is if the pope in fact taught error with regard to doctrine or morals. As near as I can figure, this has never happened. In contrast to the to multiplicity of contradictory interpretations from “perspicuous” Scripture alone, the papacy has taught a single course of doctrine.

The triumph of the papacy

So some men of the papacy failed, for a time, even for centuries. Perhaps if popes had done better at keeping the Church on the right course, if they had been reforming the Church all along, then the violent upheavals of the Protestant Reformation might never have occurred. But I maintain that in its essential purpose, the papacy never failed at all — not the way dependence on the “perspicuity” of Scripture has failed. And even the men of the papacy did not fail forever. I would argue that the Council of Trent and the Counter-Reformation, the way that, by God’s grace, the Catholic Church reformed itself, reaffirmed her doctrines, and has driven forward into modernity with a renewed heart and focus, is the greatest triumph of the papacy. I would argue that many modern popes — for example, Pius V, Pius X, and even the popes of recent memory, John Paul II, Benedict XVI and Francis, do present to the world the gospel of Christ the way a pastor and successor of Saint Peter should. Having divested itself of political and temporal encumbrances, and gained the publicity of mass communications media, the papacy of today, rather than being a “failure,” is succeeding in its mission of maintaining the unity of the faith and guiding the Church toward the gospel and salvation of Christ, perhaps better than it has in many centuries.