Adoration of the Shepherds (1646), by Rembrandt. (WikiPaintings.org)

It being Christmas, the celebration of Nativity of the Lord, it seems appropriate that I make this post that has been on my mind for a week or two, regarding the Perpetual Virginity of Mary.

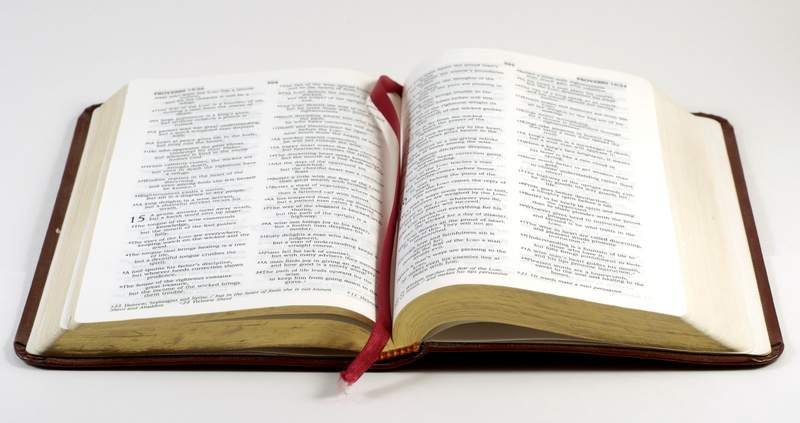

The Perpetual Virginity of Mary is one of those Marian dogmata that over much of my conversion, I affirmed more out of loyalty to the Church than out of credulity. I accepted that the Catholic Church was the true Church of Christ and the bearer of Apostolic Tradition, and therefore I would abide by her teachings. But being a lifelong Protestant, I didn’t believe that really, did I? It was one of the two doctrines I struggled with most (the other being Mary as Παναγία [Panhagia] or All-Holy), because there simply was no biblical support for it at all. In fact, Scripture says the opposite: Jesus had brothers and sisters (Mark 6:3, Matthew 13:55–56). This doctrine seemed to me to be a demonization of human sexuality, equating sex with sin and undermining the Church’s teaching on the family: the Holy Family was not a functioning, conjugal, procreative family at all, but one consisting of Mary Ever-Virgin, All-Holy; Joseph, her “most chaste spouse”; and the Christ Child, who was God Himself. The perpetual virginity smacked of the kind of argument one would expect from an admiring child: “My Mother never did that!”

It was reading Fr. Luigi Gambero’s Mary and the Fathers of the Church that opened my eyes: Belief in the perpetual virginity has been a part of the Christian faith since the very beginning. It does not undermine teachings on the family, but affirms the Full Humanity and Full Divinity of Christ. It does not equate sex with sin, but holds forth Mary’s womb as the sacred sanctuary, the Holy of Holies, the Ark of the New Covenant, that it must have been to contain God Himself. The Protoevangelium of James, an early apocryphal gospel, can be dated to around A.D. 120, and though certainly not historical, it testifies clearly to a firm belief in Mary’s perpetual virginity at that early date; in fact, supporting it seems the text’s principal aim. Though pseudepigraphical, claiming as its author James the Just, the “brother of the Lord,” the text was written within living memory of Mary. Origen, writing early in the third century, rejected the text, but nonetheless concurred with its author in affirming Mary’s perpetual virginity (Origen, Comm. Matt. 10.17). And indeed Mary’s perpetual virginity was affirmed by Fathers of the Church from then on; questioned and at times challenged, but always defended and maintained.*

* I don’t have the Gambero book with me at the moment, or I would give you some quotations; it’s still in a box somewhere lost among a mountain of other boxes. But it is chocked full of patristic quotations on every aspect of Marian doctrine, if anyone should be interested.

Over the year or two I’ve been becoming Catholic, though, I have realized that there is scriptural support for Mary’s perpetual virginity. I found another strong indication just last week, and wanted to rush here immediately to share it.

Virgin Mary (c. 1600), by El Greco. (WikiPaintings.org)

Behold, Your Mother

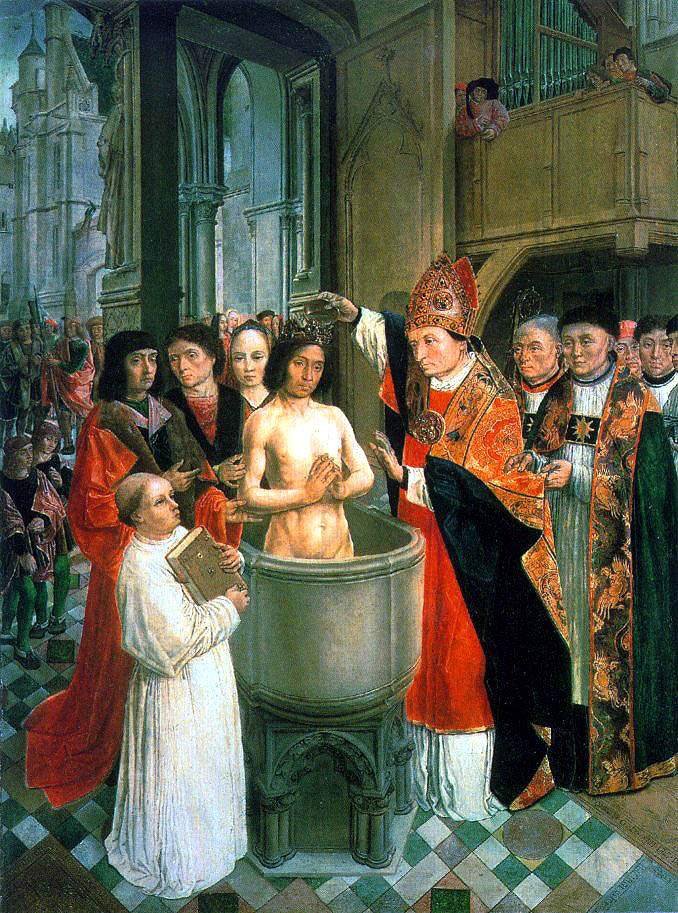

First of all, and most prominently: Jesus on the Cross, in the Gospel of John, gives his mother into the care of John (John 19:26–27):

When Jesus saw his mother and the disciple whom he loved standing nearby, he said to his mother, “Woman, behold, your son!” Then he said to the disciple, “Behold, your mother!” And from that hour the disciple took her to his own home.

It would make little sense for Jesus to place his mother in John’s care if she had other children living — and, according to the Protestant argument, she certainly did: at the very least James, “brother of the Lord,” and Jude, who both wrote New Testament epistles. Therefore it seems that James and Jude and the other “brethren” of the Lord were not “brothers” in the full and literal sense, but rather in the sense of “kinsmen.” This is not a new argument; the Fathers discovered it ages ago, as Gambero illustrates.

Maria (c. 1648), by Alonzo Cano. (WikiPaintings.org)

Apostles and Brothers of the Lord

More and more lately, as I dig deeper into the New Testament, I’ve been becoming aware of another argument that undoubtedly supports the argument the “brethren” of the Lord were not full and literal “brothers.” I explored it to some degree in my post on the Apostles named James. At the time, I considered the conclusion somewhat fanciful and poorly supported — but you know, one instance of this in Scripture might have been a case of poor wording; but two or three, and the idea gains some weight.

St. Paul, in writing to the Corinthians, examines the “rights” of the Apostles (1 Corinthians 9:5):

Do we not have the right to take along a believing wife, as do the other apostles and the brothers of the Lord and Cephas?

Appearance of Christ to the Apostles (fragment) (1311), by Duccio. (WikiPaintings.org)

In increasing order of importance, Paul lists: (1) the other Apostles, (2) the brothers of the Lord, and (3) Cephas, or Peter, the chief Apostle. Together, this statement seems to refer to the Twelve, and includes “the brothers of the Lord” among them — brothers plural, implying at least two “brothers of the Lord” were among the number of the Apostles.

Protestants, of course, argue that Paul is using the word “apostle” in a broader sense than in reference to the Twelve — after all, Paul himself was an “apostle” and not one of the Twelve. An “apostle” (ἀπόστολος) is literally anyone who has been sent. But in an analysis of the Greek New Testament, it seems that it is rarely used in this broad sense*, but that the term is a specific and technical term referring to an office of the Church, and applied almost exclusively to the Twelve and to Paul.

* See analysis below.

Which brings me to my discovery last week: In Galatians, perhaps the earliest of Paul’s letters, we have one of the most unambiguous examples of the word apostle. Following Paul’s conversion, he did not immediately go to Jerusalem to consult with “those who were Apostles before me” (Galatians 1:17). But then (Galatians 1:18–19):

Then after three years I went up to Jerusalem to visit Cephas and remained with him fifteen days. But I saw none of the other apostles except James the Lord’s brother.

Immediately I was struck. I was impressed by the example above in 1 Corinthians, though it was rather unspecific; but here we have it clear and unambiguous: James, the “brother” of the Lord, was an Apostle — and not just an “apostle,” meaning a messenger or someone who was sent, but one who was an Apostle before Paul — one of the Twelve.

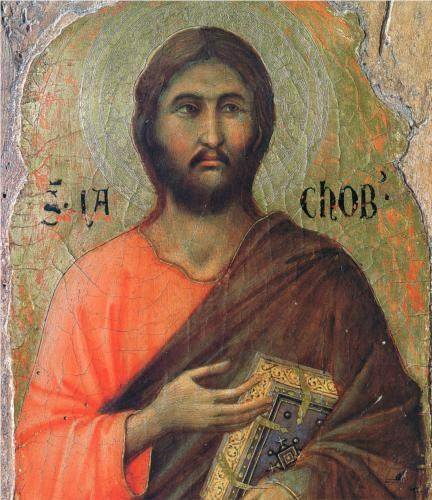

The Apostle James Alphaeus (1311), by Duccio. (WikiPaintings.org)

But how is this possible? We know the names of the Twelve Apostles, and none of them are identified as brothers of the Lord (Matthew 10:1–3, Mark 3:13–18, Luke 6:12–16, Acts 1:12–14). But there are two Apostles named James — James, called the Greater, the son of Zebedee; and James, called the Less, the son of Alphaeus. James the Greater was certainly dead by the time Paul met with the other Apostles in Jerusalem (Acts 12:1–3). So if the James whom Paul met was one of the Twelve, then it follows that James, the “brother” of the Lord, is in fact James the Less, the son of Alphaeus.

But how, then, can he be a “brother” of the Lord? Well, as I demonstrate in the other post focusing more intently on this problem, neither the Hebrew language nor the Aramaic language which Jesus spoke had a word for “cousin” — which it seems this James may have been (see the post). The word ἀδελφός in Greek, too, could carry the connotation of “kinsman” or any relative. Though the Scripture says “not even his brothers believed in Him” (John 7:5), it does not say that none of His brothers (i.e. kinsmen) believed in Him. James the Less may have been one of the less ardent and conspicuous Apostles during Jesus’s earthly life and ministry, but as a cousin Jesus would have called him “brother,” in an even closer sense than he called all the Apostles “brothers” (e.g. John 20:17) — an epithet he carried with him for the rest of his life. Following his witness of Jesus’s Resurrection, it seems that James the Less — James the Just — stepped up to his calling and served the Lord with his life.

A merry and blessed Christmas to all of you, dear brothers and sisters.

* Appendix: An Analysis of the Word “Apostle” (ἀπόστολος) in the Greek New Testament

In conclusion, though the word ἀπόστολος can have a general usage as “messenger” in Greek, in the New Testament it is rarely used in that sense (once or at the most twice out of 81 uses). Rather “apostle” is a specific and technical term referring to an elite office and ministry of the Church, holding more authority than elders (πρεσβύτεροι or presbyteroi) — who in time became priests as we know them. When any “apostles” are identified, it seems that the term is applied exclusively to the Twelve, to Paul, and twice to Barnabas.