The fifth post in my series on James R. White’s The Roman Catholic Controversy.

I said in beginning this review that I was prepared to give praise where it was due. It is due here: James White has constructed a really splendid and solid case in favor of the doctrine of sola scriptura — “by Scripture alone,” the cry of the Reformers, which White calls the formal principle of the Reformation. His argument is finely honed and well oiled, almost as a mathematical proof, and snaps shut like a steel trap. I must confess, it left me rather stunned.

I will, however, point out a few assumptions on which White rests his argument that I believe weaken it. But I was asking yesterday how any reasonable Christian could read the same sources from the Early Church that I am reading and maintain a Reformed system of belief. This is how: with arguments like this. I see no adequate way to refute this, assuming the premises that White assumes; so I can therefore only question the premises, which to me are indeed questionable.

What Sola scriptura is not

White begins by presenting six points of what sola scriptura is not — none of which I thought it was:

- Sola scriptura is not a claim that the Bible contains all knowledge (e.g. scientific, historical, political).

- Sola scriptura is not a claim that the Bible is an exhaustive catalog of all religious knowledge. (It’s not a catechism or compendium, as I’ve pointed out before — but, according to sola scriptura, it has everything the believer needs.)

- Sola scriptura is not a denial of the Church’s authority to teach God’s truth.

- Sola scriptura is not a denial that God’s Word has, at times, been spoken (e.g. the preaching of the prophets and Apostles).

- Sola scriptura is not a rejection of every kind or use of tradition (only the ones that can’t be supported by Scripture are not binding).

- Sola scriptura is not a denial of the role of the Holy Spirit in guiding the Church.

Regarding the third point: White explains that there is “a vast difference between recognizing and confessing the Church as the pillar and support of truth (1 Timothy 3:15), and confessing the Church to be the final arbiter of truth itself.” “The Church, as the body of Christ, presents and upholds the truth, but she remains subservient to it.” Catholics too agree that the Church remains subservient to the truth — that is, she serves Christ and His truth and the divine revelation of God — but the Catholic Church believes that part of her service to the truth, her responsibility, is to properly interpret that truth and teach it to her people. This is as much the Church’s God-given duty and mission as it is her authority. White charges that “Rome has gone far beyond the biblical parameters regarding the roles and functions of the Church.” He needs to define, and expound from Scripture, what he believes these biblical roles and functions to be. “The Apostles established local churches. They chose elders and deacons” — and bishops too (1 Timothy 3:1-7), I must again add, if he is in fact teaching the biblical organization of the Church — “and entrusted to these the task of teaching and preaching the Gospel of Jesus Christ.” Indeed they did; and invested them with the authority to teach. As any teacher knows, the truth — even Scripture — involves interpretation, breaking down ideas and conveying them to the student in an understandable way. I don’t know what White thinks “teaching” is, if not this. The “truth” he teaches in his church, too, is an interpretation. White misunderstands what the Catholic Church believes her role to be. He assumes, despite his statement to the contrary, that the Christian Church in fact has no inherent authority to teach the truth.

What Sola scriptura is

White next approaches a definition of what sola scriptura is.

- Scripture is the sole, infallible rule of faith (regula fidei); Scripture, and Scripture alone, is sufficient to function as such.

- All that one must believe to be a Christian is contained in Scripture.

- That which is not found in Scripture — either directly or by necessary implication — is not binding upon the Christian.

- Scripture reveals those things necessary for salvation.

- All traditions are subject to the higher authority of Scripture.

“The doctrine of sola scriptura, simply stated,” says White, “is that the Scriptures alone are sufficient to function as the regula fidei, the infallible rule of faith for the Church.” Proceeding from the very nature of Scripture as “God-breathed” (θεόπνευστος, theopneustos) revelation, Scripture is infallible and sufficient for salvation.

The Catholic Church fully agrees and affirms that Scripture is divinely inspired, inerrant, and authoritative:

Therefore, since everything asserted by the inspired authors or sacred writers must be held to be asserted by the Holy Spirit, it follows that the books of Scripture must be acknowledged as teaching solidly, faithfully and without error that truth which God wanted put into sacred writings for the sake of salvation. Therefore “all Scripture is divinely inspired [θεόπνευστος] and has its use for teaching the truth and refuting error, for reformation of manners and discipline in right living, so that the man who belongs to God may be efficient and equipped for good work of every kind” [2 Tim. 3:16-17, Greek text] (Second Vatican Council, Dei verbum III.11).

White’s argument that Scripture’s authority and sufficiency proceed from the very nature of Scripture itself strikes a chord with my argument from yesterday about the “actual authority” inherent in historical sources by virtue of what they are. Scripture too has this actual, historical authority, even aside from its divine inspiration.

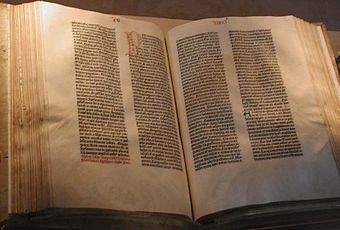

White asserts that Scripture’s sole, infallible authority is not dependent on any man, church, or council, but proceeds from the nature of Scripture itself — for indeed Scripture attests to its own inspiration by God (2 Timothy 3:14-17), and everything God says must be authoritative and infallible. This argument does have one limitation, however: for it was the Church, by Tradition, that established the canon of Scripture, over several successive generations. It is only by the Church’s actions of collecting, preserving, and transmitting Scripture that we have an authoritative collection of Scriptures at all. It was through the discernment of the Church Fathers, guided by the Holy Spirit, that the canon of the New Testament was formed: the truly inspired books selected, and others excluded. Otherwise, we would not have a New Testament to be our “sole rule of faith.” I presume this is an issue which White will address later in the book.

White claims that Scripture is “self-consistent, self-interpreting, and self-authenticating” — and doesn’t really expound on these assertions. With these claims on their face, I have a serious problem. Nothing is “self-interpreting.” Language, by its very nature, has to be received and understood and processed mentally. As Dei verbum states, “Since God speaks in Sacred Scripture through men in human fashion, the interpreter of Sacred Scripture, in order to see clearly what God wanted to communicate to us, should carefully investigate what meaning the sacred writers really intended, and what God wanted to manifest by means of their words” (III.12).

This is not even to mention that the Scriptures are written in ancient languages that are the native tongues of no one living today. Even English translations of the Scriptures must be interpreted; but to even create the English translations from the original languages requires a great deal of interpretation, in many cases when the meaning of the Greek or Hebrew words themselves is unclear or obscure, let alone the syntax and grammar. Translation is a monumental task of interpretation. To say that Scripture is “self-interpreting” undermines the hard work of both translators and teachers, and implies that the interpretation of the one making the statement is the only obvious and possible one.

Likewise, among the extant early manuscripts of the Greek and Hebrew Scriptures, there are thousands of textual variants — cases in which letters, words, or whole verses were left out, added, changed, transposed, misspelled, miscopied, or otherwise corrupted in the course of textual transmission. It is only by the arduous work of textual critics and paleographers that we have the authoritative, critical texts of the Scriptures on which grounds sola scriptura is even possible. To say that Scripture is “self-authenticating” undermines their labors.

The Westminster Confession of Faith (1646) writes of the doctrine of sola scriptura:

VI. The whole counsel of God, concerning all things necessary for his own glory, man’s salvation, faith, and life, is either expressly set down in Scripture, or by good and necessary consequence may be deduced from Scripture: unto which nothing at any time is to be added, whether by new revelations of the Spirit, or traditions of men. Nevertheless we acknowledge the inward illumination of the Spirit of God to be necessary for the saving understanding of such things as are revealed in the Word; and that there are some circumstances concerning the worship of God, and the government of the Church, common to human actions and societies, which are to be ordered by the light of nature and Christian prudence, according to the general rules of the Word, which are always to be observed.

VII. All things in Scripture are not alike plain in themselves, nor alike clear unto all; yet those things which are necessary to be known, believed, and observed, for salvation, are so clearly propounded and opened in some place of Scripture or other, that not only the learned, but the unlearned, in a due use of the ordinary means, may attain unto a sufficient understanding of them.

The claim that doctrines that are not themselves in Scripture, but “by good and necessary consequence may be deduced from Scripture,” and still meet the demands of sola scriptura, troubles me. This statement seems a catch-all for any doctrine that Protestants want to work out from Scripture, “by good and necessary consequence.” As I have pointed out before, the five solas are themselves found nowhere in Scripture, but proceed only “by good and necessary consequence” of a certain interpretation of Scripture. Likewise, the tenets of Calvinism — total depravity, unconditional election, limited atonement, et al. — are not written on the face of Scripture at all, but were worked out by Calvin and his followers through a considerable amount of interpretation and exegesis; they are nonetheless, to a Calvinist, a “good and necessary consequence” of Scripture. Other Protestants whom White, I presume, would accept as orthodox, may not find these doctrines to be “good and necessary consequences” of Scripture at all. For something that is “perspicuous” and “self-interpreting,” there is a considerable degree of interpretation and even disagreement as to its meaning.

White admits that “some measure of effort must be expended in reading and understanding the Scriptures” — but apparently, this effort does not involve “interpretation.” He notes, however, because of this required “effort,” “surely many of the disagreements people have over the meaning of the Scriptures are due not to any lack of clarity in them, but to unwillingness of people to make use of ‘ordinary means.’” We Catholics could not agree more. If Protestants would only use the “ordinary means” that would put the Scriptures into the proper historical, theological, and ecclesial context — that is, Tradition — then we could resolve our disagreements.

The Steel Trap

White’s biblical proof for sola scriptura hangs almost entirely on the interpretation of a single passage — 2 Timothy 3:14-17 (this is White’s translation):

14 But you remain in what you have learned and have become convinced of, knowing from whom you learned it, 15 and that from your childhood you knew the holy Scriptures, which are able to make you wise unto salvation by faith which is in Christ Jesus. 16 All Scripture is God-breathed, and is profitable for doctrine, for reproof, for instruction, for training in righteousness, 17 in order that the man of God might be complete, fully equipped for every good work.

White seems to know his Greek (he likes to show it off; I guess I do too), but one thing I would point out, that doesn’t particularly affect the sense of the passage, is that the main verb in the first verse, μένε (mene) is imperative — it’s a command, not an indicative statement. Most published translations read “But you, remain in what you have learned . . . ” Also, the word he translates “Scriptures” in verse 15 and the word he translates “Scripture” in verse 16 are two different words — the former being γράμμα (gramma), which can be any kind of writing (the ESV translates this phrase “holy writings”), and the latter being γραφή (graphē), which in the New Testament is only used of Scripture. In any case, the translation of this verse, so far as the words themselves, is clear.

White’s proof follows like so (I am simplifying it and presenting it as a logical proof; White does not):

- The Scriptures, by their very nature as God-breathed, are able to make one wise unto salvation. Scripture in itself is sufficient for salvation.

- The Scriptures, being God-breathed, i.e. breathed by God, have their origin in God, and therefore as the Word of God have God’s authority.

- The Church, in Scripture, has and hears God’s Word, which has God’s authority. Therefore the authority of the Church to teach, rebuke, and instruct is derived from Scripture itself; the Church has no authority that does not derive from Scripture (“despite Roman Catholic claims to the contrary”).

- Because Scripture is God’s voice, it is “profitable for doctrine, for reproof, for instruction, for training in righteousness, in order that the man of God might be complete, fully equipped for every good work.”

- Therefore the man of God can be both saved and made complete with Scripture alone. Nothing else is necessary, or Paul would have mentioned it.

- Therefore Scripture alone is sufficient to make the man of God complete for “every good work.” No man of God needs anything else for the purpose of ministry.

- The Roman Catholic Church teaches doctrines that are not found in Scripture, either directly or by any logical deduction of implication — for example, the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin (the belief that the Virgin Mary was bodily assumed into Heaven at the end of her earthly life).

- If these doctrines were true, it would be a “good work” to teach them.

- Since Scripture equips the man of God to be complete for every “good work,” and Scripture does not equip the man of God to teach the Assumption, then it follows that teaching the Assumption is not a “good work.”

- Therefore, the doctrine of the Assumption, and other non-biblical doctrines taught by the Catholic Church, are not necessary to be taught, or Scripture would equip the man of God to teach it. These doctrines are not necessary for salvation, or Scripture, being able to make one wise unto salvation, would teach them.

And the trap clangs shut.

“Hence,” says White triumphantly, “the Protestant says the doctrine is not binding upon the Christian; the Roman Catholic, having accepted the doctrine on the authority of the Roman Church, is forced to conclude the Bible is insufficient as a source of all divine truth.”

But wait. White isn’t done there. He proceeds to another leg of his argument, based on Matthew 15:1-9:

Then Pharisees and scribes came to Jesus from Jerusalem and said, “Why do your disciples break the tradition of the elders? For they do not wash their hands when they eat.” He answered them, “And why do you break the commandment of God for the sake of your tradition? For God commanded, ‘Honor your father and your mother,’ and, ‘Whoever reviles father or mother must surely die.’ But you say, ‘If anyone tells his father or his mother, “What you would have gained from me is given to God,” he need not honor his father.’ So for the sake of your tradition you have made void the word of God. You hypocrites! Well did Isaiah prophesy of you, when he said:

“‘This people honors me with their lips,

but their heart is far from me;

in vain do they worship me,

teaching as doctrines the commandments of men.’”

Jesus rebukes the Pharisees for following the tradition of the elders — which the Pharisees believed to be God-given and authoritative, though it was not written in the Law — even though it broke the commandments of God, what was given as the Law, and were written in Scripture. Therefore all “tradition of the elders” is subject to Scripture, and it is to be tested against the known standard of Scripture.

White assumes that Sacred Tradition is contrary to or contradicts Scripture — but it isn’t and doesn’t. I assume, though, I will hear more about this later.

Assumptions

These are the questions I have with White’s argument.

The Nature of Scripture – The Old Testament

First, when Paul was writing to Timothy, the Holy Scriptures he was referring to were only the Old Testament; the New Testament had neither been written nor collected. White acknowledges this much. “No one would wish to say that the Old Testament is wholly adequate and the New Testament is superfluous and unnecessary,” he admits. “The thrust of the passage is the origin and resultant nature of Scripture and its abilities, not the extent of Scripture (i.e. the canon),” argues White. “That which is God-breathed is able, by its very nature, to give us the wisdom that leads to salvation through faith in Christ Jesus (‘all things necessary for man’s salvation’) and to fully equip the man of God for the work of the ministry (‘all things necessary for . . . faith and life).'”

White continues to press this argument. Even acknowledging that Timothy would have heard and been brought to faith by the Gospel through hearing oral preaching, not through Scripture at all, he asserts that “the content of the teaching Timothy has received is identical with, not separate from, that found in the Word of God.” White insists that this oral preaching of the Gospel is the same content Timothy would received in the Holy Scriptures which he “had known from childhood.” “The message he has received in the Gospel is to be found in the Sacred Scriptures themselves” — in the Old Testament. Really?

Does White really mean to say that all Scripture, being God-breathed, is sufficient and able by its very nature to bring one to salvation in Christ Jesus? Is, say, the Book of Leviticus? What about Esther, which doesn’t even refer directly to God? Every book in the Old Testament, it’s true, is laced with metaphors and types and prophecies pointing to Christ — but are these prophecies, these precursors, sufficient in themselves to bring one to faith in Jesus? How could they be, if they don’t even mention Him? I’ve never heard of someone (other than Paul himself) “getting saved” reading only the Old Testament, with no other knowledge of Christ. Doesn’t faith in Christ necessitate knowledge of Christ? For “how are they to believe in him of whom they have never heard?” (Romans 10:14).

If Paul, referring to the Old Testament Scriptures, said “all Scripture is God-breathed” and “able to make wise for salvation in Christ Jesus” — and yet the Old Testament Scriptures aren’t able to bring one to faith in Christ Jesus — then it follows that Paul meant something else other than the way White and Protestants have interpreted this statement.

The Nature of Salvation

This raises another important point: The Scriptures are able to make Timothy wise unto salvation. According to the Protestant view, isn’t Timothy already “saved”? Isn’t justification by faith a once and for all experience, a done deal? Does this passage not suggest the Catholic view, that salvation is a process? Reading the Scriptures, then — any Scriptures, including the Old Testament (even including Leviticus, which I found illuminating) — would make the believer, who already has faith in Jesus and is already on that road, “wise for salvation.” They would add wisdom and foster spiritual growth and further him along the path — and we believe they do.

Oral Preaching and Tradition

No, in fact Timothy wasn’t brought to faith in Christ by Scripture at all, but by oral preaching. That preaching was sufficient to bring him to faith, along with every other believer during the Apostolic Age and before the New Testament was canonized. They didn’t have Scripture pertaining to Jesus. The preaching and teaching of the Apostles was transmitted orally by tradition for at least the first several generations of Christians; it was that tradition that brought the earliest believers to faith in Christ, not Scripture. And if that tradition continued — as we in the Catholic Church believe it did — would it not remain sufficient to “make wise for salvation”?

White stated earlier that “the content of the teaching Timothy has received is identical with, not separate from, that found in the Word of God.” He made this argument for the Old Testament Scriptures, to which Timothy had access, and this seems to fail on its face. But suppose White were arguing instead that the content that would be contained in the New Testament was identical with the message Timothy heard — which seems to be more logical and consistent with his thesis; that God breathed all that was sufficient for man to be saved into Scripture, and so the message Timothy heard is what God would have caused to be written. This argument, too, seems to make an unreasonable assumption. White acknowledges that God’s Word, at times, was spoken rather than written. How does White know — how can he assume — that there was no more to the message God spoke through the Apostles orally, that was not later written into the New Testament, the Sacred Tradition that the Catholic Church teaches? White assumes, by sola scriptura, that Scripture is all there is; but he cannot prove sola scriptura using sola scriptura. Scripture itself attests that not everything that was taught by spoken word was written (2 Thessalonians 2:15).

According to Protestants, Scripture contains all the Word of God that’s necessary to bring one to faith in Christ. The rest, according to their view — the other doctrines in Tradition that aren’t in Scripture — aren’t necessary. Even supposing that were true, it doesn’t necessarily follow, though, that because they are not necessary, they are not good, or are necessarily false, or should be discarded. God is a God of overabundance, not just “enough.” Why would I want only what was sufficient for salvation? Our Catholic faith is overflowing in its fullness — and every bit of it is good and worthy and “makes us wise unto salvation” — by my definition above, of furthering us along that path.

“All Good Work”

Okay, I changed my mind. I would like to take exception to one point in White’s interpretation of the Greek of the 2 Timothy 3 passage. For the Greek phrase he translates “every good work” — πᾶν ἔργον (pan ergon) — another possible reading is “all kinds of good work.” In fact, this is the reading preferred for this verse by the BDAG, the premier, most authoritative lexicon of New Testament Greek, which White himself calls to support his translation of another word. πᾶν ἔργον could, instead of every, mean every kind of or all sorts of.

White takes a very narrow, strict, legalistic reading of the word πᾶν — but Paul was not constructing a legal or logical argument here, but exhorting Timothy about doing good works. Just as we would say in English, “The Bible is useful for all kinds of things,” without meaning that the Bible is literally useful for all, each and every kind of thing, the same sense of the word πᾶν was common in Greek. While White does attempt to limit the scope of Paul’s “every good thing” to only those good things that pertained to Christian ministry, this sense isn’t at all clear from Paul’s language. But suppose for a moment that’s what Paul meant. “Scripture fully equips you for all kinds of good work in ministry.” White is very careful to make clear that the word complete (ἄρτιος, artios) is to be understood in the sense of “fitted, complete; capable, proficient; able to meet all demands.” Does Scripture literally make one fully equipped, “able to meet all demands” of “all kinds of good work” in ministry? Does it, say, teach you to preach a rhetorically good sermon? Does it provide you with a workable geography of Asia Minor? Does it teach, in plain terms, the Trinity, or the hypostatic union of Christ, or the five solas, or even its own canon? So, not quite “all kinds of things.” Paul is speaking as a rhetorician, not a logician.

Also, can Scripture be used for anything besides “good work” in ministry? Certainly. It can even be used for evil, such as justifying slavery or rape or genocide. So clearly Paul’s statement here is not meant to be taken as a legalistic, limiting, exclusive statement that “Scripture equips you for all, each and every good work you will ever need to do in ministry — and nothing else that would possibly be not so good.”

The Sufficiency of Scripture

Even if we were to accept White’s interpretation that Scripture in itself is sufficient to “make one wise unto salvation” — Scripture nowhere states, nor is it clear, that Scripture is the only thing that is sufficient to bring one to faith in Christ. In fact, as I have pointed out above, it is clear that the oral preaching of the Apostles — and its oral tradition, the passing of the apostolic teachings from one generation of Christians to the next — was sufficient to bring hearers to faith in Christ, before the New Testament was written, canonized, and disseminated.

That is not even to mention the oral preaching of preachers to this day — which also is sufficient to bring hearers to faith. White would argue that preachers today are preaching Scripture, that they are using the words of Scripture and the content of Scripture — but, since the oral teaching of the Apostles and their successors was also sufficient, it is clear that this Tradition also contained content that is sufficient for salvation.

White makes another unreasonable assumption about Scripture’s sufficiency. Paul says that Scripture is able to “equip the man of God for every good work.” According to White, if any other authority were necessary, Paul would have told Timothy. But we only have two surviving letters of Paul to Timothy. How do we know there weren’t other letters in which Paul gave Timothy other essential information? How do we know Paul didn’t impart other essential teachings to Timothy orally? We don’t have proof that he did (beyond the reception, through Tradition, of doctrines not in Scripture), but we don’t have proof that he didn’t. White assumes, because he believes Scripture is sufficient, that if anything else were necessary, Paul would have said so in Scripture. Because he didn’t, it must be true that Scripture is sufficient. White assumes his conclusion. It narrows to a tautology: Scripture is sufficient because it is sufficient.

The Authority of the Church

White denies repeatedly that the Church has inherent authority beyond the the authority of Scripture itself. “The authority of the Church is one: God’s authority,” states White. The Catholic Church agrees — the Church’s authority is God’s authority which Christ imparted to the Apostles. But White argues that the only authority God imparted was that contained in Scripture, His authoritative voice speaking to the Church and through the Church. “The divine authority of the Church, then, in teaching and rebuking and instructing, is derived from Scripture itself, despite Roman Catholic claims to the contrary.”

But Scripture itself very clearly presents a different picture. On numerous occasions, Christ Himself imparted authority to the Apostles, and charged them with a divine mission, and promised them power to fulfill it: to Peter, the authority to “bind and loose,” and the “keys of the kingdom” (Matthew 16:17-19); to the rest of the Apostles, the authority to “bind and loose” (Matthew 18:18); the authority to forgive sins or withhold forgiveness (John 20:22-23); the promise that the Holy Spirit will guide the Apostles into all truth (John 16:13-15); the Great Commission (Mark 16:15-18); and the promise of power from the Spirit (Luke 24:49). This is not an exhaustive list by any means. The Catholic Church believes that by apostolic succession, the authority of the Apostles descends to today’s pope and bishops. The authority of the Catholic Church derives from the authority of the Apostles, which was imparted to them by Christ. To the Church, its exercise of authority over Scripture and Tradition is God’s own authority.

The Magisterium of the Church has the authority to interpret Scripture definitively. White asserts that Scripture is the “higher authority” of Protestants, and that the individual believer has the authority to interpret Scripture for himself or herself. White asserts that Scripture is “self-interpreting,” and yet acknowledges that individual believers may come to different conclusions. Above it all, there seems to be a “correct” interpretation — the “self-interpreting” one — to which White is appealing. To what authority is he appealing? By what authority can White claim that his interpretation is right and the Catholic one is wrong?

Conclusions

As I said in the beginning, my arguments here do very little to argue against sola scriptura; they merely undermine White’s defense of it. There are no doubt other defenses, and even deeper, heartfelt convictions, that maintain Protestants in the belief.

This question begins, and ultimately ends, with authority. What do we believe our authority is? If we trust in the authority of the Church, her claims to authority rest on Scripture, history, and the writings of the Church Fathers. If we trust in sola scriptura, then we trust in the Protestant Reformers — whose interpretations of Scripture and doctrines ring just as true now as they did 500 years ago.

It is incumbent upon Protestants to prove that the Early Church ever believed or taught sola scriptura, that Scripture was ever their sole rule of faith. In my opinion as an historian, there is no evidence to suggest that anyone before the Reformers ever did. Even if Scripture seems to support a system of belief built upon sola scriptura, it cannot be true if no one in the Early Church ever held it. We have a sufficient store of writing from the first generations of Christians that this question — whether they adhered to sola scriptura, or also founded their beliefs on oral tradition — is answerable.

If it wasn’t held by the Early Church, then it wasn’t taught by the Apostles, and it wasn’t taught by Christ. It seems, in my historical opinion, an unlikely doctrine to have ever been taught. If it had been, the Apostles would have been much more concerned with writing, and the Early Church would have been much more concerned with preserving the apostolic letters that were no doubt written but no longer survive.

The Apostles taught by spoken word, and their spoken word was passed on to the next generations of Christians by oral tradition. The Christian faith was transmitted in such a way for several generations. Even after Scripture was canonized, the Church would not have abandoned the tradition of apostolic teachings. Over time these were written down by the Church Fathers.

The objection by educated Protestants — as it will no doubt be of James White — is that the Early Church almost immediately fell away from the true doctrine taught by the Apostles of sola scriptura. As diligent and faithful as the Early Church was, this seems unlikely; and it presumes a position of ecclesial deism.

In the end, the question comes down to whose authority we trust more: the Church Fathers, who attest to the beliefs of the Early Church, or the Reformers, who posit that the Early Church held doctrines that cannot be attested.