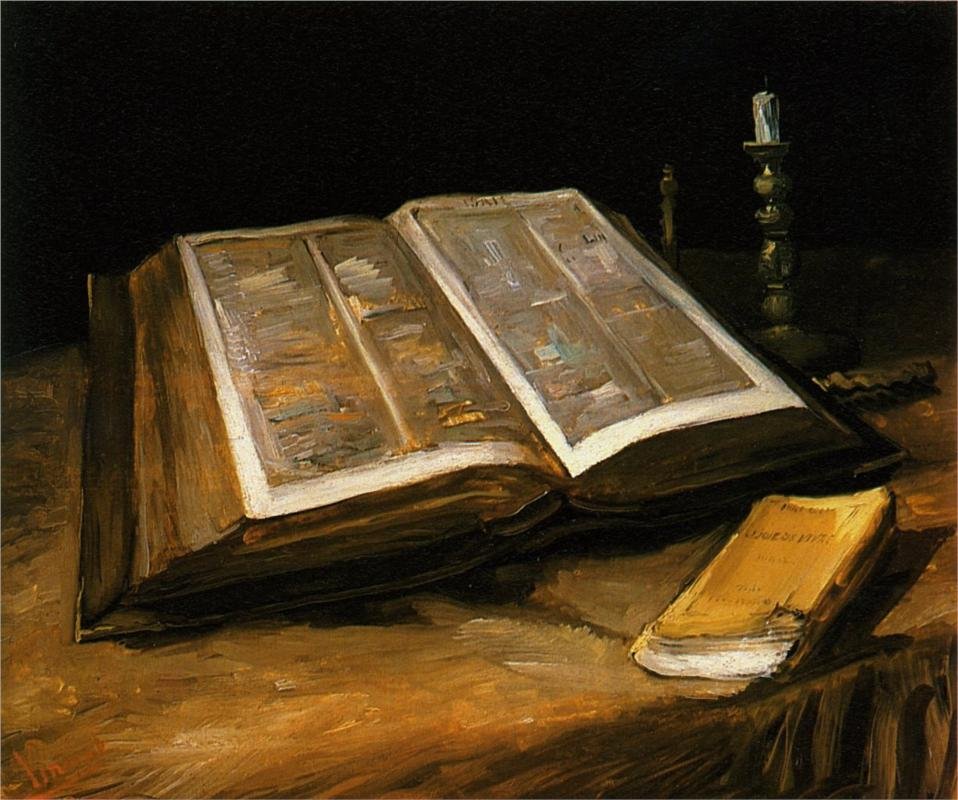

Previously we examined the claim made by anti-Catholics that “Catholics cannot interpret Scripture for themselves.” I showed, by the teachings of Vatican II, that Catholics are not only able to read and interpret Scripture, but encouraged to. There are, however, other objections and other texts that I’ve seen raised to pursue this claim. I’d like to examine a few here.

“It is not ‘freedom’ to be ‘free’ to interpret ‘in accord with the Church'”

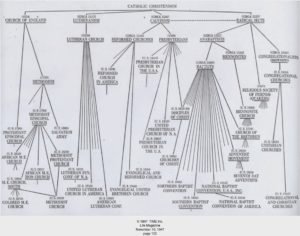

I have heard the objection that to say that “Catholics can interpret Scripture for themselves … but only in accord with the teachings of the Church” is a contradiction, a statement that Catholics have freedom while not being “free” at all. This is not so. For one thing, as I pointed out previously, it is only a small subset of Scripture that the Catholic magisterium has given official, authoritative interpretations of. The vast majority of the Bible, Christians must read, and are encouraged to read, for their own spiritual benefit. Catholics will, naturally, read and interpret Scripture through the lens of Catholic doctrine and theology. To say that Catholics must “interpret Scripture in accord with the teachings of the Church” is no more profound a requirement than the expectation that Protestants will read and interpret Scripture according to Reformation precepts. Protestant churches also require their members to read and teach Scripture according to their own standards.

I have heard the objection that to say that “Catholics can interpret Scripture for themselves … but only in accord with the teachings of the Church” is a contradiction, a statement that Catholics have freedom while not being “free” at all. This is not so. For one thing, as I pointed out previously, it is only a small subset of Scripture that the Catholic magisterium has given official, authoritative interpretations of. The vast majority of the Bible, Christians must read, and are encouraged to read, for their own spiritual benefit. Catholics will, naturally, read and interpret Scripture through the lens of Catholic doctrine and theology. To say that Catholics must “interpret Scripture in accord with the teachings of the Church” is no more profound a requirement than the expectation that Protestants will read and interpret Scripture according to Reformation precepts. Protestant churches also require their members to read and teach Scripture according to their own standards.

Anti-Catholics, naturally, think the Catholic interpretation of Scripture is wrong, and that Catholics would surely discover “the truth” if they were but free to read and interpret Scripture for themselves. This claim is another way of dismissing Catholic theology and interpretation, claiming that no one would come to such interpretations if they were not imposed on the faithful by the Church and required to be believed — but truthfully, Catholic exegetes arrive at, believe, and defend the Catholic interpretation of Scripture with just as much faith and just as much integrity as Protestants.

There is a right answer

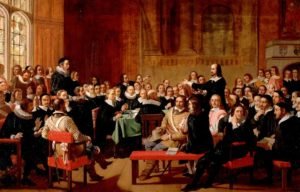

Herbert, John Rogers, RA (c. 1844), The Assertion of Liberty of Conscience by the Independents at the Westminster Assembly of Divines (Wikimedia).

One fallacy I often fell into as a Protestant — one I doubt that many anti-Catholics, at least, will be subject to — is the thinking that it is a denial of freedom for a church to subject its faithful to a single authoritative interpretation at all — my supposition being that everybody is free to come to their own interpretation. It is indeed true that everybody is free to come to their own interpretation, but being part of a church — any church — entails either agreeing with that church in one’s interpretation, or else subjecting one’s personal interpretation to that of a teacher. This is true no less for Protestants than for Catholics. Anti-Catholics object to the very idea of the Catholic Church claiming the authority to teach.

The truth is, there is one right answer to questions of biblical interpretation — because there is only one truth in Christ. It is true that in many cases, the senses of Scripture are deep and multi-layered — there is more than one sense of Scripture that is true. It is also true that in many cases, the meaning is not completely clear, and such passages are open to various interpretations. This is true for exegesis under the Catholic Church as it is for Protestants. The Church exhorts the Catholic faithful to biblical scholarship in order to gain a deeper understanding of Scripture. But in other cases, there is indeed a place for definitive answers. Protestant theology has its uncompromisable precepts as surely as does Catholicism, and Protestant churches and Protestant exegetes claim to teach the only true interpretation of Scripture as surely as does the Catholic Church. Protestant churches, too, require their faithful to submit to their understanding teaching of the truth — or else be asked to leave the church. What opponents object to is not that the Catholic Church claims to teach the truth of Scripture, but that she claims to speak with absolute authority about it.

The Council of Trent on Sacred Scripture

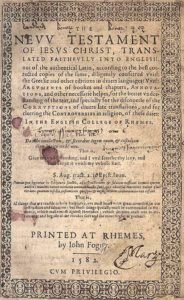

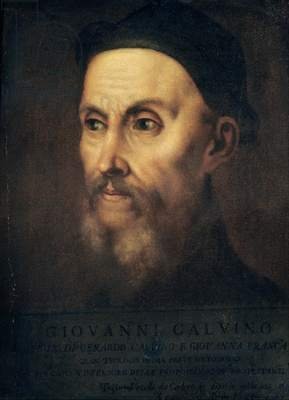

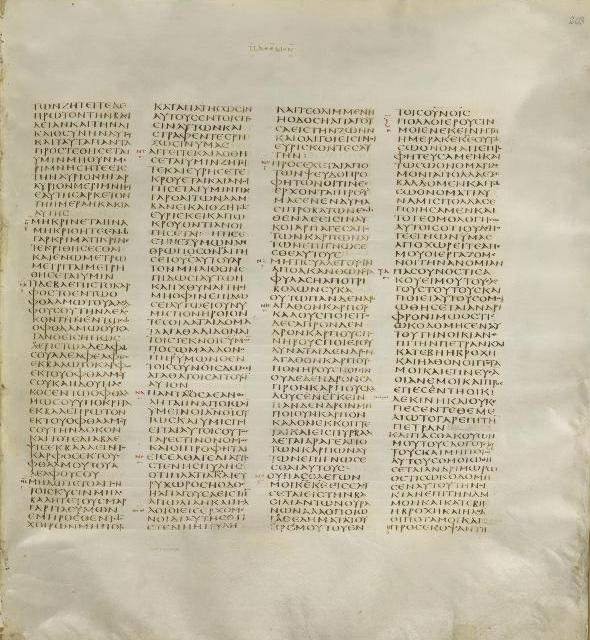

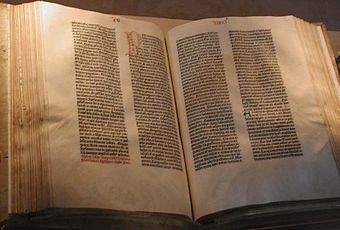

One text I have often seen cited against the Church in connection with these claims is from the Council of Trent’s Decree concerning the Edition, and the Use, of the Sacred Books (Fourth Session, April 1546). Since the Council of Trent was called to address the crisis of the Protestant Reformation, these decrees are particularly relevant to addressing Protestant claims about the interpretation of Scripture. Related to this is the supposition that Catholics were forbidden to read, possess, or translate Scripture, which is an equally empty claim (there is a very long history of Catholic Bible translations, even in the Reformation era), but a claim to be examined another day. Regarding the interpretation of Scripture, Trent taught:

Furthermore, in order to restrain petulant spirits, [the Synod] decrees, that no one, relying on his own skill, shall,–in matters of faith, and of morals pertaining to the edification of Christian doctrine, –wresting the sacred Scripture to his own senses, presume to interpret the said sacred Scripture contrary to that sense which holy mother Church,–whose it is to judge of the true sense and interpretation of the holy Scriptures,–hath held and doth hold; or even contrary to the unanimous consent of the Fathers…

This does indeed, at first read, appear to teach that “no Christian can interpret Scripture for himself.” But there are several key phrases which make clear that this statement is entirely consistent with the teachings of the Second Vatican Council explicated previously. Trent does not in any way forbid Christians to read and interpret Scripture for themselves. Rather, it teaches that “No one shall … presume to interpret sacred Scripture contrary to that sense which holy mother Church … hath held and doth hold; or even contrary to the unanimous consent of the Fathers” — in other words, in the way that Christians have understood and taught doctrine from the beginning of the faith. It bars contrary interpretations just as Protestant teaching bars Catholic interpretations — otherwise, there is no truth and everything is open to debate.

- “No one [shall], relying on his own skill … wresting the sacred Scripture to his own senses”: This does not speak against informed exegesis of the Word of Scripture made in good faith, but against those who would twist Scripture “to his own sense,” away from what it actually says, for one’s own purposes.

- “in matters of faith, and of morals pertaining to the edification of Christian doctrine”: These are specifically the areas in which the Church, in teaching the faith, has authority to teach.

- “contrary to that sense which holy mother Church … hath held and doth hold”: In passages where the Church has taught an official and authoritative interpretation of Scripture, it is the obligation of the faithful to hold according to that sense. As I have already written, there are many passages where no official interpretation has been offered, and the faithful are free to read and interpret for themselves. But even in those places, it is the obligation of the faithful to bear in mind the sense of the faithful, the way in which the Catholic Church reads and understands the doctrine of Scripture.

- “or even contrary to the unanimous consent of the Fathers”: There are many ideas about which the Church Fathers are not in “unanimous consent.” But where they are, certainly, a reader of Scripture is on very thin ice indeed to offer an interpretation or a teaching that no one before, ever has found or arrived at before.

The intent of this passage is to guard the faithful against “petulant spirits” — those who would offer novel and sensational interpretations of Scripture with no support at all but their own interpretation. This has been and continues to be a problem in Protestantism. If no one before in all the history of reading or interpreting the Scriptures over twenty Christian centuries has come to your particular interpretation, and your interpretation is based on nothing more than your own opinion, then there is a good chance that what you are exercising is not “freedom,” but hubris.

“The laity is not competent or authorized to speak in the name of the Church”

One puzzling text that was recently raised to me in a conversation is a quotation from the 1913 Catholic Encyclopedia article on “The Laity.” With regard to doctrine:

The body of the faithful is strictly speaking the Ecclesia docta (the Church taught), in contrast with the Ecclesia docens (the teaching Church), which consists of the pope and the bishops. When there is question, therefore, of the official teaching of religious doctrine, the laity is neither competent nor authorized to speak in the name of God and the Church (cap. xii et sq., lib. V, tit. vii, “de haereticis”).

I am not sure I understand the objection. This is basically a re-statement of what has already been said: the magisterium (Ecclesia docens) has the authority to teach doctrine, while the layperson does not. This is really no more profound a statement than saying that “the Supreme Court of the United States has the authority to give the official interpretation of U.S. law, while John Smith on the street is neither competent nor authorized to speak in the name of the United States government.” John Smith is not an official representative of the United States, nor a legislator, nor even a lawyer; so while he is free and possibly even competent to read the law and tell you what he thinks it means, he is not in a position to offer any kind of legally authoritative opinion. When he speaks, it may be a perfectly reasonable explanation, but it is not legally binding.

Likewise lay Catholics are perfectly able to read, interpret, and offer explanations of Catholic doctrine, Sacred Scripture, or Sacred Tradition, but they cannot speak for the Church or for God. Now, Protestants or anti-Catholics may object here on several grounds. First, they object to the idea that there is any real distinction between clergy (bishops, priests, and deacons) and laity (non-ordained laypeople) at all, arguing that the “priesthood of all believers” makes every Christian equal in authority. But the fact is that every institution has its leadership and its official representatives. What they may reject to, further, is the idea that the Church is an institution (even if, we say, it is an institution of Jesus Christ and the Apostles). Finally, I am sure they object to the idea that the officials of this institution have the authority to “speak in the name of God.” This is a tall claim, and is not the sort of language that is often used today, but, it’s true, the Catholic Church believes that Jesus imparted the authority to teach the truth of God to His Apostles and they to their successors the bishops.

Critics are free to object, but this passage only underscores the points already made: Just because a lay Catholic does not have the authority to make official, authentic pronouncements of Church doctrine does not mean that he cannot read and interpret Scripture and doctrine for himself, for his own benefit, and offer his own interpretation. To the claim that “Catholics cannot interpret Scripture for themselves,” this passage too falls flat.

“For themselves”?

What does it ultimately mean, to suppose that Christians have the freedom to read and interpret Scripture “for themselves”? In the context of these anti-Catholic arguments, it means, I suppose, “without the Catholic Church telling them otherwise.” As I have pointed out elsewhere, no church, no denomination, no system of theology is free from the influence of somebody giving their opinion. A Protestant is free to interpret “for himself,” but only within the Protestant precepts of sola fide and all the rest — otherwise he ceases to be a Protestant, is labeled a heretic, or converts to another form of Christianity. A church naturally instructs its faithful in the truth as it understands it.

Does the Catholic Church teach her faithful the truth she has received? Absolutely, as she is required and charged to do, by the Lord and by Scripture (1 Timothy 4:11). Does she forbid her faithful from reading, interpreting, understanding, or exploring Scripture, to discover the truths of the Lord and the faith for themselves? Absolutely not. She instructs such believers in the proper way and the best way to read and understand Scripture, yes; she does not leave her children “on their own” or “to their own devices” in such understanding, to be tossed to and fro by all the diverse opinions of Protestantism and the world. In the end, the Catholic faithful have free will to believe and follow what they will; but they are never left without a teacher or a mother to show them the truth.