Yes, I have a thesis to write, but inspired by Laura’s brilliant and succinct one-post conversion story, I figured I had better get on the stick and get to the end of mine, and thought I would spend a few minutes on another chapter. If you’re new here, here’s the story so far.

The Four Doctors of the Western Church: Pope St. Gregory the Great, St. Ambrose, St. Augustine, and St. Jerome.

I’ve written some before about how the Latin language led me to Dr. G and The Society, our university’s society of students and professors devoted to the study of ancient languages and literature — and how Dr. G led me to the Church Fathers, and finally to Rome itself — the literal, actual city of Rome, not yet the Church. Dr. G and the Society have been such a powerful influence on my life in so many ways. They were my society. For so many years, I devoted myself to the Society and served it faithfully. I was the secretary in perpetuity, and I loved my office. But after my new lease on life, I decided that I had more to give.

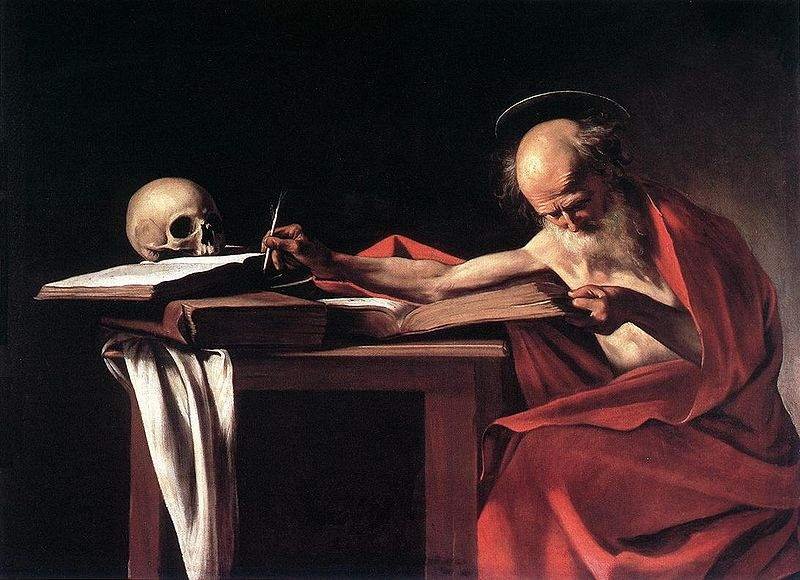

So I ran for imperator (that is, president; technically, I ran for vice imperator, the heir presumptive to the next year’s imperator). I presented at my election that I already had a packet of readings planned for my year; and it was to be Christian Latin. I had a list of so many greats from whom we would have readings — St. Augustine, St. Jerome, St. Gregory the Great, St. Ambrose, St. Cyprian, Saints Perpetua and Felicity! The first semester would be the Latin of the Church Fathers, and the second semester would be Medieval Latin. I was excited about it, and my excitement was infectious, for a time.

St. Jerome Writing (1606), Caravaggio. (Wikimedia)

Except, of course, that I hadn’t really read the Church Fathers. I knew them by name and reputation, but I hadn’t read their writings. So over the course of the next year, I immersed myself in patristics. I discovered, to my delight, that my university, otherwise a backwater to classical learning, had a not-insignificant collection of the Church Fathers, not only Schaff's Ante-Nicene Fathers and Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers in English, but a fair many Latin editions. I discovered J.P. Migne's monumental Patrologia Latina and Patrologia Graeca — not in our library, sadly, but in the ether of the Internet, where all things, both hideous and wonderful, from every part of their world, find their centre.

If I wasn’t already in love with the Church Fathers and with the faith of the Early Church, that love affair began then. I discovered such deep, such uncompromising, such uncomplicated faith — so real and immediate and passionate and personal. Christ was their Way, their Truth, and their Life, in a way that our modern world seemed to have lost sight of. I lamented more and more the loss in today’s evangelical Christianity of — something. I still couldn’t quite comprehend or put into words what it was that was missing. It was authority — a firm, absolute security of doctrine, apart from any issue of “interpretation”; a reliance on something concrete and settled and institutional that we today no longer had access to. It wasn’t just a “personal” faith in Christ, in the “individualistic” sense that it had so much come to mean. It was a deep and thoroughgoing commitment to the Body of Christ as a whole, to unity and orthodoxy and universality. It was a devotion to Christ’s Church, One, Holy, and Apostolic — and Catholic.

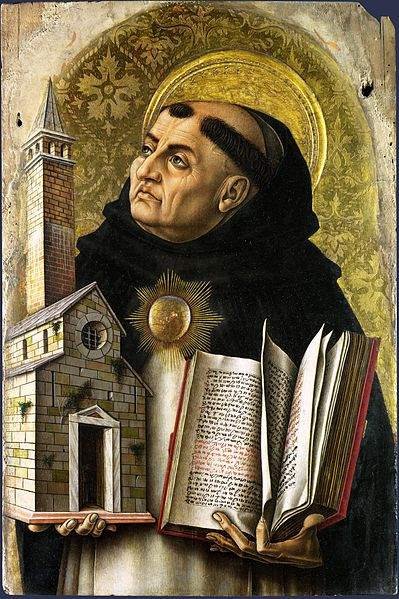

St. Thomas Aquinas (15th century), by Carlo Crivelli (Wikimedia). If I had known St. Thomas then, I might not have been so hard on scholasticism.

If anybody had approached me then and suggested that I examine the modern Catholic Church, I would have politely refused — and I did, repeatedly. My friend Hibernius had converted to the Catholic faith after discovering the Early and Medieval Church in Dr. G’s history courses. I had been to Mass with him once in the States, and then to Mass in Rome itself! But in my mind, still, the Catholic Church was something dead, cold, and empty — something that had once been alive and on fire, in the glorious days of the Church Fathers and the Medieval Doctors of the Faith in which I was then consumed, but which the cool rigor of scholasticism had quenched. In seeking to combine faith and logic, scholasticism had defined everything, even defining away miracles and mysteries. It had subjected a real, living relationship with Christ to rules and regulations, formulae and liturgy, rote and repetition. It had sought to put God in a box, and instead buried any sense of true faith. What was lost from the Church Fathers, I admitted resignedly, was something that couldn’t be regained.

I blamed Abelard. He was one of the pivotal figures in Dr. G’s accounts of the history of the Church, and his confrontation with St. Bernard over Abelard’s “strange doctrine” was one of the turning points. St. Bernard became for me a hero — the last breath of a real, personal, emotional relationship with Christ, one that combined faith and reason without subjecting either to the other — the last bastion of Christianity as Christ intended it, winning the battle against Abelard but losing the war. Abelard represented to me everything that I imagined wrong with the Catholic Church — faith buried under logic; a need for being holy subjugated by a need for being right — and he personally someone dissolute and arrogant and insufferable. (I still to this day, despite having studied him a bit more and coming to understand him better, have negative feelings toward Abelard.)

From the point of Bernard and Abelard’s conflict forward, I imagined, was the root of the true schism in the Church: the Catholic Church into a terminal scholastic death spiral, the inevitable end of which would be the awakening of the Protestant Reformers and their struggle to regain the true faith — and their overcompensation, casting away so many blessed babies with the dirty bathwater, ultimately severing any connections with history and authority and reason, leading the way for the individualistic, purely subjective and emotional Christianity — in so many ways, equally empty and equally lost — from which I’d run away as an evangelical.

So that was where I stood five or six years ago, and I continued to stand there stubbornly for another three or four years, right up until the time I first went to Mass at St. John’s in Oxford. As the Venerable Fulton Sheen said, “There are not one hundred people in the United States who hate the Catholic Church, but there are millions who hate what they wrongly perceive the Catholic Church to be.” I was one of those millions, not too terribly unlike many of the anti-Catholic Protestants I talk to online — though I was rather sad about the perceived state of the Catholic Church, and lacked any real commitment to Protestantism, either.

But for the time being, I delighted and reveled in the Church Fathers, and longed for what it was they had that we no longer had. Their Church was the true Church. I fully comprehended that modern, evangelical Christianity resembled in no way the Early Church — not even those evangelicals who claimed to be “re-creating the biblical model of the church.” I grasped vaguely that something more than “Scripture alone” might be needed to regain the faith I longed for, and I regretted the antipathy of my evangelical brethren for anything that had preceded themselves. I understood more and more that the Catholic Church — at least, up until the Middle Ages — carried forward the faith of the Church Fathers. But there was still a disconnect between that realization and any affinity for or even interest in the modern Catholic Church. And it was ignorance, and prejudice, and stinging bitterness. God would have to sweep those away, in a babbling brook of cool, fresh water, before I could open my eyes.