I do hope this can be a very short, breathless break, since my thesis is picking up momentum and I don’t want to do anything to put on the brakes. But this is something that has come up frequently in my conversations with Protestants: Many Protestants misunderstand the idea of anathema, as in the formula used by the councils of Church in rejecting various doctrines — most particularly the canons of the Council of Trent in rejecting Protestant doctrines:

CANON IX. If any one shall say, that by faith alone the impious is justified; so as to mean that nothing else is required to co-operate in order unto obtaining the grace of justification, and that it is not in any respect necessary that he be prepared and disposed by the movement of his own will; let him be anathema. (Council of Trent, Sixth Session [1547], Decree concerning Justification [trans. Theodore Alois Buckley])

(For the most piercing and enlightening commentary I’ve ever read on these pronouncements of Trent concerning justification and other doctrines, you should read my dear frend Laura, a former Protestant like myself who can sweep away Protestant questions and confusion like nobody else I know.)

So anathema: To translate the word etymologically and literally, it can mean “accursed”; even “devoted to destruction.” Many Protestants understand that when the Council of Trent declared holders of these doctrines to be “anathema,” it was “devoting them to destruction” or even pronouncing “eternal damnation” on them — such that Protestants think that to “anathematize” someone is to “damn them to hell.” Naturally, Protestants are rather offended by this, and rightly hold that any Church that would pronounce eternal damnation on someone is not acting according to God’s will — which is that all men should be saved (1 Timothy 2:4).

But that’s not what the council was saying at all. Through generations of use, beginning even with the usage of St. Paul in the New Testament, anathema came to mean something other than its literal, etymological meaning — particularly in Latin, and particularly in the councils of the Church. Anathema sit (“Let him be anathema”) became a legal formula, something repeated by the councils to announce a particular, traditional judgment. When the councils pronounced holders of a doctrine anathema, it marked a formal excommunication from the Church: nothing more and nothing less.

Excommunication, too, is often misunderstood; even though it is a biblical doctrine that many Protestants practice (I have heard them refer to it euphemistically as “disfellowship,” but the concept is the same): to remove one who is unrepentant in sin or incorrigibly teaching error from one’s church body, as St. Paul recommended in 1 Corinthians 5, even using language evocative of anathema (“deliver this man to Satan for the destruction of the flesh”, v. 5).

But the Catholic Church’s model of excommunication is just as St. Paul’s: it is not a pronouncement of eternal damnation, but a disciplinary measure designed to motivate the sinner to repentance and reconciliation. The full verse above reads, “Deliver this man to Satan for the destruction of the flesh, that his spirit may be saved in the day of the Lord Jesus.” The goal of excommunication is not damnation, but salvation. It is the Church’s mission to love and lead the lost to salvation in Christ, not to hate or damn to hell (hello Westboro Baptist Church). Excommunication is tough love, the Holy Mother Church kicking her prodigal son out of the house until he gets his act together. And just as with the father of the prodigal son (Luke 15:11–32), it is the Church’s great joy to accept and embrace her lost son back as soon as he repents and seeks forgiveness (cf. 2 Corinthians 2:5–11).

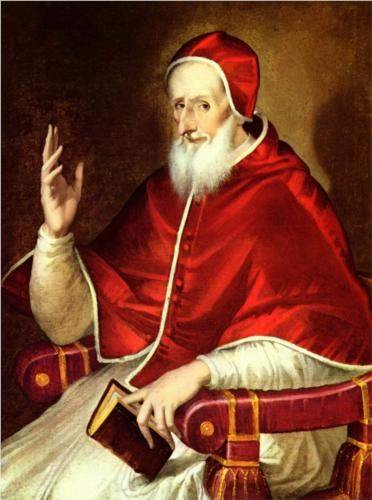

El Greco, Portrait of Pope Pius V (c. 1605) (WikiPaintings.org)

“But… but… you’re making that up!” I’ve heard Protestants say. “You’re just trying to change the meaning to whitewash what the council did!” “Show me where it says that this is what it meant!” Well, simple logic dictates that the Church was not pronouncing a permanent, irrevocable damnation here: If that were so, then the Church would not have gone to such great effort to win back our separated Protestant brethren during the Counter-Reformation (notably through the efforts of the Jesuits) and ever since: If any holder of Protestant doctrines was irretrievably damned — if the Church wanted to damn him — then why bother? Many, many separated brothers, even whole countries, such as Poland and Lithuania, were brought back to the Catholic faith, and accepted with open and loving arms.

Also, for what it’s worth, the canons of the councils of the Catholic Church apply only to members of the Catholic Church: after one has formally separated from the Catholic Church and rejected its authority, then its disciplinary pronouncements have no more bearing on him. The declaration of anyone as “anathema” at the Council of Trent does not technically apply to Protestants today, only to Catholics who were espousing those doctrines. You can’t very well be excommunicated from something you were never formally a part of.

But here are a few sources explaining the meaning of anathema, not made up by me or anyone else:

ANATHEMA. A thing devoted or given over to evil, so that “anathema sit” means, “let him be accursed.” St. Paul at the end of 1 Corinthians pronounces this anathema on all who do not love our blessed Saviour. The Church has used the phrase “anathema sit” from the earliest times with reference to those whom she excludes from her communion either because of moral offences or because they persist in heresy. Thus one of the earliest councils — that of Elvira, held in 306 — decrees in its fifty-second canon that those who placed libellous writings in the church should be anathematised; and the First General Council anathematised those who held the Arian heresy. General councils since then have usually given solemnity to their decrees on articles of faith by appending an Anathema.

Neither St. Paul nor the Church of God ever wished a soul to be damned. In pronouncing anathema against wilful heretics, the Church does but declare that they are excluded from her communion, and that they must, if they continue obstinate, perish eternally. (W. E. Addis, & T. Arnold, A Catholic Dictionary. New York: Catholic Pub. Soc., 1887], 24)

And for a bit lengthier and more precise:

Anathema. — This may be a convenient place to explain the true meaning of the phrase, “Let him be Anathema,” with which these and so many other definitions of doctrine close. The word is of Greek origin, and exists in that language in two forms, distinguished by a very trifling difference of spelling, but very distinct in use. Both are derived from a verb meaning “to set aside,” and in one form (ἀνάθημα) the word is used of something precious, set aside for the service of God, such as the gifts with which the Temple in Jerusalem was adorned (St. Luke 21:5; see also 2 Maccabees 9:16). But the word occurs also in another form (ἀνάθεμα), and with this spelling it is employed to signify a penal setting aside, whether of a thing which has been used as the instrument of wickedness, or of a person who has lost his social rights by crime. It occurs in both senses, in a verse of Deuteronomy (7:26). St. Paul uses the word more than once, to signify that a person is not worthy to be admitted into the society of Christians (1 Corinthians 16:22; Galatians 1:8, 9).

In the language of the Church, the phrase, “Let him be Anathema,” is used in the same manner as by St. Paul, and is a form of assigning the penalty of excommunication for an offence; when used, as it often is, to enforce definitions of faith, it means no more than this; but sometimes an Anathema seems to mean an excommunication pronounced against an offender with solemn and impressive ceremonies, which, however, do not alter the nature of the punishment. As we remarked in the place cited from our first volume, no anathema or other act of a human judge can take away the grace of God from the soul, if by any error the judgment has been pronounced against an innocent man.

In one place (1 Cor. 16:22) St. Paul adds to the word Anathema “Maranatha;” and the same is sometimes done by Councils of particular Churches, but the usage has not passed into the general Canon Law. It has been supposed, but wrongly, that the addition of this word signifies that the censure will never be relaxed (Benedict XIV, De Synod. 10, i. 7). Maranatha is in truth an Aramaic word, belonging to a language familiar to St. Paul and most of his readers. It means “The Lord is at hand,” and has the same force as when this expression is used in its Greek form. (Philippians 4:5) The phrase enhances the force of that to which it it appended, by solemnly reminding the reader that Christ will come again, to judge the world. (S. J. Hunter, Outlines of Dogmatic Theology, 3rd ed., vol. 2 [New York: Benzinger Bros., 1896], 399–401)

And for a secular source, lest you think this is a Catholic conspiracy to change history:

anathema, (from Greek anatithenai: “to set up,” or “to dedicate”), in the Old Testament, a creature or object set apart for sacrificial offering. Its return to profane use was strictly banned, and such objects, destined for destruction, thus became effectively accursed as well as consecrated. Old Testament descriptions of religious wars call both the enemy and their besieged city anathema inasmuch as they were destined for destruction.

In New Testament usage a different meaning developed. St. Paul used the word anathema to signify a curse and the forced expulsion of one from the community of Christians. In A.D. 431 St. Cyril of Alexandria pronounced his 12 anathemas against the heretic Nestorius. In the 6th century anathema came to mean the severest form of excommunication that formally separated a heretic completely from the Christian church and condemned his doctrines; minor excommunications, while prohibiting free reception of the sacraments, obliged (and permitted) the sinner to rectify his sinful state through the sacrament of penance. (“Anathema,” in Encyclopedia Brittannica)

You’ll find much the same in any other scholarly source (barring the likes of Jack Chick and Loraine Boettner).

Once again, I fail, predictably, at brevity. I’d better get back to work. I do hope this will be helpful to some seeker.