My blog motor has been sputtering. I’ve been doing other things: reading, learning, changing. I’ve been receding deeper and deeper into my hobbit-hole. My prayer every day is that God pour me out and fill me up with His love. I have several posts that are simmering half-stirred, but none of them have really motivated me. So I thought I should take a step back, a wider look, and return to what I originally set out to do: to tell the story of how and why I came to the fullness of the Catholic Church.

I’ve been telling that story at length, and I was getting close to the end — that is, back to the beginning and up to the present. Now this next chapter has been on my mind a lot lately as I find myself once again at a similar place: having finished a degree, standing at a juncture, wondering what to do next.

To my surprise and my unexpected blessing five years ago, I found myself a teacher at Veritas, a classical school and homeschool cover. There were a lot of things happening then that were important to my journey, but in this post I thought I’d recount how my time at Veritas led me nearer to the Truth of the Church.

It’s often said that one doesn’t truly understand a subject until one teaches it to another; and I certainly found that to be true. I also found that I loved teaching. I was teaching a full bag of subjects: Medieval European history to the upper class (grades 9 through 12, or approximately ages 14 to 17); Post-Reconstruction U.S. history (that is, ca. 1877 to ca. 1965) to the lower class (grades 7 and 8, or ages about 12 to 13); English grammar and vocabulary to both classes (with a focus on Latin and Greek roots for the lower class); Latin to the lower class; and Koine Greek to a few brave souls of the upper class.

Catholici me docent linguam latinam

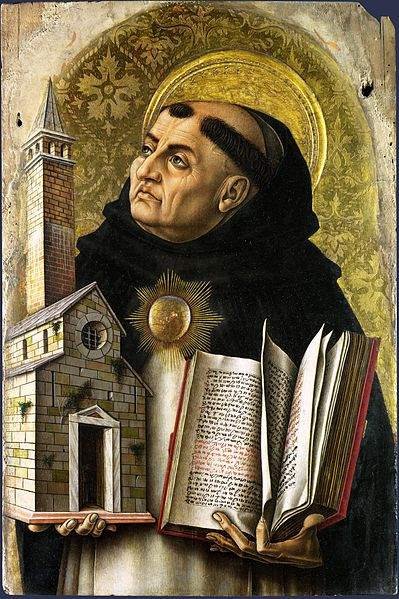

St. Thomas Aquinas (15th century), by Carlo Crivelli. (Wikimedia). St. Thomas is a patron of educators and academics.

In my Latin class, per the direction of Mr. H our headmaster, I taught the Ecclesiastical Pronunciation of Latin — that is, how Latin is pronounced in the Roman liturgy. I had been taught at university using the Reconstructed Classical Pronunciation. To illustrate the difference very briefly: in the Ecclesiastical pronunciation of the Pater Noster (the Lord’s Prayer), we say, Pater Noster, qui est in caelis, with the caelis pronounced ˈtʃeː.liːs (chē-līs or chay-lees: ch as in cherry; ay as in pay; lees as in lease). In Classical Pronunciation, one says ˈkaj.liːs (kai-līs: kai as in kayak; lees as in lease).

Now, I was accustomed to Classical Pronunciation, and at first Ecclesiastical Pronunciation sounded very strange and foreign to me. But it so happened that even in this generally Reformed stronghold (Veritas met at a Presbyterian church, you recall), even deep in the Protestant territory of North Alabama, I had a small handful of Catholic students, including a smart young man named John D who reminded me a lot of myself. John and his family, I soon learned, attended a Traditional Latin Mass in Huntsville — and John was very quick to correct me when I slipped back into Classical Pronunciation as I so often did. Before too long, Ecclesiastical Pronunciation was like honey to my ears: so natural and beautiful, the way Latin lived in our world and the way real people pronounced it. At the height of the year, the whole class actually learned to say the Pater Noster in Latin like good Catholic schoolchildren.

The reason for our using Ecclesiastical Pronunciation was that the textbook we were using was Henle Latin by Fr. Robert Henle, S.J., which has found a popular following among classical, even Protestant, homeschoolers (mostly by virtue, I think, of being old and not-newfangled). And it was a decent book, despite being directed primarily toward teaching Caesar’s Gallic Wars: our vocabulary consisted mostly of military terms and words for killing (so the girls especially complained, and I agreed). But we also learned that Maria orat Christianis (Mary prays for Christians) and various other Christian concepts with a distinctly Catholic flavor; and the book was complete with charming illustrations of Catholic life. I didn’t realize at the time how much I appreciated it. After all, if anybody else had a fair devotion to the Latin language, it was the Catholics.

Φῶς Ἱλαρόν (Phos Hilaron or “Hail, Gladdening Light”)

My Greek class, sadly, was not very successful. The half an hour or so we had each week just wasn’t enough time to effectively teach a language so foreign to everybody; and only a few students, mostly the ones who were new to Veritas and out of the Latin loop, chose to participate. I consider it a victory that I was at least able to introduce them to the Greek alphabet and hopefully open up a curiosity in the Greek New Testament for them.

Light shines through the dome of the ancient church of Hagia Sophia in Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul).

When it came time to teach the Latin class the Pater Noster in Latin, I thought it would be cool to teach my Greek students something to recite also. At that time, David Crowder Band, one of my favorite groups, had recorded a translation of the Phos Hilaron, one of the earliest recorded Christian hymns outside of Scripture. I don’t think anyone else got as excited about it as I did. But I got excited about it! Here I was, peering into the very dawn of Christianity in its very native tongue! In both my Latin and Greek classes, I felt the deep sense that I was approaching the historic Church — which, at that time, I had not yet identified with today’s Catholic Church.

But day by day — though I still had no idea — I was being drawn to her.

And that’s still only the half of it! Stay turned for more, as I taught medieval history to the upper class, with a mindful focus on the Christian Church.