Hi, I’m back in school now and still trying to organize my time. I haven’t had much of a chance to sit down and write, especially not about any large subjects; but in today’s Mass readings, an idea hit me forcefully that I think I might be able to comment on quickly. This will be an exercise in brevity, both of length and time.

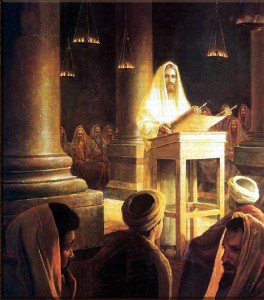

I’ve always been struck by today’s Gospel reading (Mark 1:21–28): “The people were astonished at His teaching, for He taught them as one having authority.” Jesus was something completely different, something no one had ever seen before. Not since Moses himself, the codifier of the Law, had anyone spoken with such authority on the Law and the mind of God toward human behavior.

He stood in vivid contrast to the so-called authorities of the day, the Pharisees and Sadducees, the scribes and scholars of the Law. The only authority they ever offered was their own, as they disputed endlessly on the interpretation and application of the Law. They had sola scriptura: Scripture alone, the divine and authoritative Word of God, in the Law and the Prophets — and yet they did not have authority. For all their scholastic eminence and merits, they could offer only disagreement and division. Jesus did not come to give God’s people more of the same: another holy book or another teacher or even another prophet. He came to give them something radically new and different.

Jesus spoke with authority, such that there was no question, dispute, or ambiguity about what He meant. And he gave that same authority to His Apostles (Matthew 10:1, 40; Luke 10:16), to speak and to teach with His voice. And the Apostles gave their successors, the bishops, that same authority to teach (1 Timothy 4:11, etc.). And this is the same authority with which the Magisterium of the Church teaches today.

By contrast, see the state of teaching in the Protestant churches. When a preacher stands up to teach, he may speak with self-assurance; he may speak from the divine, authoritative Word of God; but he gives an interpretation; he does not speak with authority. In the Protestant world, there are only endless disputes concerning doctrine and interpretation. Sola scriptura — “Scripture alone” — without prophets, without a Christ — is all the Jewish people had before Jesus came. And He came to deliver us from that chaos and confusion, as surely as He came to deliver us from sin and death. The Protestant proposition seeks to return the Church to that: to deny and reject the very authority that made Jesus Christ’s revelation so radical and so powerful a revolution.

This is a pretty weak jab… usually it is Protestants who wrongfully claim that “sola scriptura” existed from the beginning! The scribes and pharisee had not only the Tanakh, but the Talmud, and the Midrash, and the other assorted important texts of Judaism, a long series of sacred tradition that has a parallel with the sort of sacred tradition that Christians created.

If there had been no debate on ambiguity in the early church, there would have been no need for all the writings of the church fathers. And you make it sound as if the Magisterium itself has never had to debate and interpret the teachings it passes on. On the contrary, the Roman Catholic priest doesn’t have to interpret anything not because it doesn’t need to be interpreted, but because the authority to interpet doesn’t lie with him. Interpreting is done elsewhere, but it is still done.

Is this the same Pastor Ken who’s been commenting on my blog for so many years? You’ve been ostensibly less friendly in your last few comments to me.

You’re right that my comments here are a simplification (and perhaps my comparisons to sola scriptura inaccurate), but I think your response even further underscores my point. The Pharisees and Sadducees did have a lengthy, voluminous, and complex tradition of scholarship and commentary (so do Protestants); these sources of Jewish tradition were held as authoritative. The Jews of Jesus’s day did have a ruling and authoritative legislative assembly, the Sanhedrin, who were even said to have had the power to bind and to loose. And yet when they taught, they did not speak with authority.

You’re also right that individual bishops and members of the Church’s Magisterium have sometimes disagreed. Some, even large numbers at a time, have outright left the teaching of the truth (let alone teaching it with authority), as in the Arian controversy and other heresies. Individual bishops do not speak with the same authority of the Apostles — but all the bishops combined, guided by the Holy Spirit, collectively have the authority of the Magisterium and do have that same authority. They do interpret, they do sometimes debate, but when they speak, they speak with one, binding, authoritative voice, and there is no ambiguity.

Where is this kind of authority present in the Protestant world? You’re right that the Pharisees and Sadducees did not have sola scriptura: they had something much more; and yet they did not speak with authority. Sola scriptura seeks to deprive the Church not only of the radical authority that Jesus brought and invested in His Apostles (cf. Matthew 18:18), but to leave her with something less than what the people of God had in former times: to take away what even the Jews had and leave only a bare book without even the authority to interpret it. In terms of authority, the Protestant proposition is not a revolution but a regression.

I’m letting my stress show… you’re right, I haven’t been checking my words before typing them. The comment equating the scribe and phrarisees with Protestant “sola scriptura” really ruffled my feathers, and I still think it’s a cheap shot, but I shouldn’t have lashed out. I’m sorry, Joseph–I’ve not been setting us up for good conversation like we used to have. Hopefully, this comment is better.

I like your comment better than the actual post, as it helps me to better understand how the teaching authority works in the Roman Catholic Church, which I know I’ve studied; but it’s always good to have a reminder.

The issue of authority in Prostetant churches is as wide and varied as the church’s themselves. Some (too, too many) go way too far to the other extreme–the individual pastor has all of the authority in all matters, even though he or she will profess to be only reciting “what the Bible says”, and therefore is also claiming to have the straight line back to God. That is most certainly a regression, and it is painful to see so many who hold this thinking, as it is blindly ignorant and leads to many more abuses and crises of faith.

In American Lutheran churches, the question was never really quite solved as I understand it. Authority is something that is shared among the community–or, rather, the community itself (with differing interpretations of what that might mean) is the authority.

One of my seminary professors once joked that when they were deciding what the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America would look like after the merger of the American Lutheran Church, the Lutheran Church in America, and the American Evangelical Lutheran Church (clearly they all drew the same words out of a hat when picking names), the question of who should be invested with teaching authority came up. Should it be with the pastors? No, you can’t really trust all of them, can you? Bishops? Definitely can’t trust them! Teaching theologians? RUN FOR THE HILLS, they can’t be trusted either! Now, I’m not exactly sure how much of that is actually true (he did like to spin a tale), but it demonstrates that the Lutheran churches were hesitant to assign one group perpetual teaching authority. This hearkens back to the original purpose of the Reformation–to call out abuses by an authority open to no correction. By investing one body with that authority, it sets itself up to abuse that authority.

So, the best I can describe it in the ELCA, is that the authority rests in what the church decides, after careful deliberation, discussion, taking into consideration the opinions of 1) tradition, 2) history, 3) the Conference of Bishops, 4) the teaching theologians, 5) pastors, 6) the laity. It does help that the church acknowledges that it is only making the best decision it can, trusting in the work and power of the Holy Spirit in the process, while also acknowledging that we may be proven wrong down the road.

I am intrigued by your analysis of the scribes and pharisees in relation to the huge breadth of history, tradition, and writings that they had, and yet still did not teach with authority. I would add to the list that they also had the covenant relationship, a special relationship with God. And yet, with all that, even God’s own spirit and presence, they still became mired in their own workings and doings, failing to properly use the authority that had been granted to them.

Even after the coming of God-with-us, Jesus Christ, who established a new(?) authority, God did not abandon the Jewish people.

I say I am intrigued by that analysis, because, from a Reformation point-of-view, that was the situation as it was perceived in the church in the 1500s. That’s just one perspective, though.

It’s no problem. I’ve been pretty stressed, too, and I understand and forgive you. 🙂 I’m sorry if my initial wording of things was abrasive. I wrote it in a pretty big hurry and excitement.

I’m glad we agree on that: not only the individual pastor, I’m sure you realize, but especially in Evangelical Christianity, often the individual believer, “solo Scriptura,” so they say.

Thanks for explaining all this. I realize that many of the Protestant churches did and do struggle to set up some framework of ecclesistical authority. This seems to be an acknowlegement that there is supposed to be and must be some authority in the Church. Luther and the other Reformers, though, placed themselves above all Church authority, insisting Scripture alone was their only ultimate authority, and taking it as their initiative to reject the established authority in the Catholic Church. It seems to me that it’s awfully hard to get the wild horses and “petulant spirits” (to quote Trent) of assuming one’s own authority back into the gate once they’ve already been let out — and that’s precisely why Protestantism is so fragmented, and has been from the beginning. It entails in its very initial proposition the idea that there is no absolute, God-given Church authority, but only the authority that we establish and acknowledge for ourselves.

It’s interesting to me that you didn’t even mention Scripture; presumably (and rightly so) you consider it a part of tradition? But we Catholics would say Scripture stands above the rest of “tradition,” and clarify that Sacred Scripture is a part of Sacred Tradition, something concrete and immutable that was given by God through Christ and handed down by the Apostles.

And what does it help that the church acknowleges the fallibility of its decisions? I suppose, if one has indeed set up one’s own authority, then certainly one must accept it as fallible. 😉 But this doesn’t seem to be the attitude toward Church authority that we find in Scripture (cf. Acts 15) or the early ecumenical councils.

I think that’s precisely why Jesus ripped the Pharisees so badly for being so bound by their traditions: not that they had traditions, but that they came to depend more on their own carrying on of those traditions than on God. They allowed their traditions to obscure the special relationship between them and God and all the authoritative revelation they had already been given. Still, it seems to me that they lacked something. I’m going to insist on my comparisons to the way many Protestants carry on sola scriptura: The Jews had received a divine revelation; and all the while declaring that revelation to be authoritative, they proceeded to subsume it to their own authority, bicker about it, become divided. God saw that we needed one shepherd (Ezekiel 34:23) and so sent us Christ; and His authority was that of a shepherd, not a king: to teach, guide, and save His people. And it makes no sense, in the scheme of revelation, for God to establish this new authority and then take it away, to leave us with less than what we had before.

(And yes, I know the answer of many Protestants would be that “No, that authority continues to be with us through the Holy Spirit” — but for all the things Jesus said the Holy Spirit would be, “shepherd” was not one of them; and if the Holy Spirit is supposed to be our “one shepherd,” He is either not a very good shepherd or we are not a very good flock.)

God bless you and His peace be with you, Ken.

Happy New Year, Joseph,

I certainly don’t want to be the victim of errant interpretations so I wonder if you might tell me where I can find the official, “magistierial”, Roman interpretation of the verses you quote (Mark 1, Matthew 10, Luke 10.) Are there any “official” Catholic interpretations for those?

I think you and I both know that there are not.

So, where does that leave your argument? Why should we believe your personal interpretation of these verses? Is your interpretation any better than any Protestant preacher? If so, why?

It seems you have added a defeater to your own argument.

Good luck with your studies.

Hello, Paul. Thanks for the comment. I hope you are well.

I can never tell if you are mocking me, or if you actually believe the fruitless argument you keep repeating to me. I give you the same answer again and again, and you do not respond to it, only slink away and come back a few months later with the same argument as before. My conclusion from that has been that either you accept my response, and only keep bringing back the same argument to heckle me, or else you have no answer for me, and yet can’t bring yourself to accept the truth. I think you are far more intelligent than that, so I would really appreciate it if you would follow through with your argument this time and explain to me why you don’t accept what I’m about to write out for you once again.

The Magisterium is a teacher, not a dictator. Her role is to instruct the faithful in the faith, to teach them how to follow the Lord Jesus Christ, how to live and be Christians, how to become mature believers, not infants (Hebrews 6:1) — not how to be mindless sheep who cannot think for themselves, who must rely on the dictates on the Church to understand every jot and tittle of Scripture. I, at one time as a Protestant, thought this about the Catholic Church; it did not take very much reading at all to disabuse me of that mistake.

You love to quote Trent to me, in apparent horror and indignation; and I’ve exposited this passage to you several times already. But this is the key and the refutation to the argument you keep making:

You’ll notice this word sense I’ve emphasized: Latin sensus, meaning “opinion, thought, sense, view, understanding, reason” (cf. Lewis and Short) — the “common sense” of the Catholic Church, that which the Church “hath held and doth hold.” This does not say, “contrary to the concrete dictates” of the Catholic Church. I say again, and you surely realize, that the Magisterium of the Catholic Church has given “concrete dictates” (comprised almost completely by the canons of the ecumenical councils and the teaching documents of the popes) about only a minuscule portion of Sacred Scripture — and in every one of those cases, such proclamation was only made because that “common sense” of the Church was called into question or disputed. In other words: The expectation of the Church is that we will know better, that we will have “common sense,” without having to rely on her dictates. But the Magisterium’s teachings are there, which form and guide that “sense” with authority that no Protestant either wields or accepts.

So to answer your questions: Whether or not there are “official” teachings (meaning those taught authoritatively by ecumenical councils or popes) about these verses is irrelevant. The relevant question is, am I interpreting these passages in accord with the “common sense” of the Catholic Church, the way these verses have been understood by Christians throughout the ages and from the beginning? And answering that question requires a little study; and surprise: I do study, to be sure I am understanding the traditional Christian teaching. And you can, too. Any good Catholic commentary on Sacred Scripture (and there are many) will give an overview of the way passages of Scripture have been understood, historically, traditionally, and patristically, by the “common sense” of Christians from the beginning, will give appropriate citations to writings of the Church Fathers and documents of the Magisterium, and will explain where there are differing interpretations. In short: My “personal intepretation” is not my “personal interpretation” at all. And yes, the timeless “sense” of the Church is much better, much more authoritative, than any Protestant preacher.

The way Protestants use that phrase, “personal interpretation,” and the way you use it (“Is your interpretation any better than any Protestant preacher?”) refers to reading Scripture — and some Protestants, I do credit, do consult the patristic understandings of the texts — and forming one’s own opinion, presuming the personal independence — from the Church, from the Fathers, from history — to interpret it any which way one pleases, even if this opinion be contrary to everything Christians have ever believed, held, or taught: the Protestant Reformers themselves being a case in point. My “personal interpretation” does involve my faculties of reason and interpretation, but contrary to the “personal interpretation” of your average Protestant preacher, it involves a willful teachability and willingness to be informed and instructed by the “common sense” of Christians throughout the ages, guided by the authoritative Magisterium of the Church. And I can, will, and do support such “personal interpretation” with citations to the Church Fathers and teachings of Magisterium: that is, in fact, what my blog is about.

My question to you: What makes you think your own “personal interpretation” of these and other verses is better than twenty centuries of Church Fathers and doctors and teachers and theologians?

To return to your previous question: there actually are “official” teachings about the verses in question:

Since these are rather pivotal verses to the authority of the Magisterium, I could cite a lot more in the way of “official” intepretations for you if you’re interested. So your challenge falls flat on another front: Yes, there are “official, ‘magisterial’, Roman interpretations” of these verses; here is where you find them.

May the peace of Christ be with you.

So Joseph

On your analysis, where was the authority in the church before the Incarnation? Is it your position that there was no authority until Mark 1 or the establishment of the Roman church?

When the prophets spoke were their pronouncements merely “interpretations” that God’s people were free to accept or reject?

How exactly did God work in His creation before the first pope?

Paul,

I presume you know Theology 101: “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. He was in the beginning with God; all things were made through him, and without him was not anything made that was made” (John 1:1–3). Jesus was there, in all His authority, from the very beginning: it is He through whom all things were made. Neither Jesus nor His authority came into existence at the Incarnation.

No, that is not my position. I don’t know whence you could have presumed that. Authority belongs to God, and has since the beginning. It might surprise you to learn that the Catholic Church does not believe herself to be God, but merely His servant.

God gave His people various authorities throughout the unfolding of revelation and the history of salvation: first through the covenants with Noah and Abraham, then through the Law given to Moses, then through the Aaronic priesthood and the Davidic kingship, then through the voices of the Prophets. (You might read my comments above to Pastor Ken if you haven’t already.) So no, there was no absence of authority before the coming of Christ or the establishment of the Church: far from it. And yet, despite all the authority God’s people had already been given, they were stunned at the newness and boldness of the teaching of Christ with authority.

The words of the Prophets — as well as everything else that came to be written in Sacred Scripture — were the very, absolute Word of God, He speaking to us through them. And no, God’s people were not “free” to accept or reject their words, or subject them to interpretation: but that is in fact exactly what they did. We humans have a need for shepherds to guide us (cf. Jeremiah 23:4, Ezekiel 34:23).

Read the Old Testament: it answers exactly that question.

Hi Joseph,

I certainly don’t mean to heckle you but, like Pastor Ken, probably feel a little frustration at these entirely ahistorical arguments that you make. And I bring Trent to your attention because that is a legitimate example of Magisterial authority. And because Trent was affirmed by later councils. So it’s fascinating to me, Joseph the way that you have to avoid the “common sense” reading of Trent because it conflicts with your own interpretation. That’s all.

Be that as it may, let’s approach this your way.

1. You wrote: “The Magisterium is a teacher, not a dictator…

Reply: One of my observations about your writing on the Catholic church Joseph, is that it is consumed in the post-Vatican II era. So when you write something as crazy as the “Magisterium is…not a dictator” you display a naivete that is…well… hard to imagine. Have you never heard of the Papal States? Or the Inquisition (now know as the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith)? Or haven’t you read any of Pope Leo XIII or Pius X’s dictates with regard to Catholic teaching? Are you aware of the “policing” that was mandated by Rome against American priests in the early 20th century? I don’t mean to be unkind Joseph, but those are all part and parcel of what “Magisterium” is and that is very “dictatorial”.

But our topic today is Authority, so let’s leave the dictatorial aspects of the Magisterium for another time.

2. Continuing, you wrote: The Magisterium“… has given “concrete dictates” (comprised almost completely by the canons of the ecumenical councils and the

teaching documents of the popes) about only a minuscule portion of Sacred Scripture — and in every one of those cases, such proclamation was only made because that “common sense”

of the Church was called into question or disputed.

So very much in this one!

Reply 1: Leaving aside the canons of the ecumenical councils and papal writings, where can I find the authoritative “concrete dictates” on Scripture? Vatican I after all, says “that meaning of holy scripture must be held to be the true one,…” Where is this “true one” meaning??

Reply 2: In instances where a council contradicts a pope or vice versa, where can I find the Roman Catholic authority to resolve those disputes? And more importantly, if I were a Catholic living in a time when a Council was the highest authority of the Roman church, would I have been wrong to follow their authority? How about since I live in a time when the Pope is held to be the supreme authority. How can I know that that is right? Can they both be right, Joseph?

Reply 3: If there really is such a thing to a Roman Catholic as “common sense” with regard to the Scriptures, doesn’t that authority exist in each Roman Catholic independent of the Magisterium? In other words, Catholics have their own “private interpretation” for most of Scripture? Why did the Magisterium keep the Scriptures away from Catholics for so many centuries if it was “common sense”?

Reply 4: Is Matthew 16:18 part of that “miniscule portion of Sacred Scripture” that the Magisterium has authoritatively dealt with? If so, what is the “authoritative interpretation”? Since this verse is so fundamental to Rome’s claim of authority Joseph, this should be easy to answer. As far as I know, Rome has claimed at least five (5) interpretations through the years and that has always bothered me. Can you tell me what the authoritative version is? I’d be grateful.

3. Joseph continues further: “Any good Catholic commentary on Sacred Scripture (and there are many) will give an overview of the way passages of Scripture have been understood, historically, traditionally, and patristically, by the “common sense” of Christians from the beginning, will give appropriate citations to writings of the Church Fathers and documents of the Magisterium, and will explain where there are differing interpretations.

”

1. Reply: Why, Joseph, would I have to consult ”many” Catholic commentaries on Scripture when you claim that Rome has a singular authority? Why many when Vatican I says that Scripture has “one” meaning? Does it take “many” commentaries to explain a single authoritative interpretation? Hasn’t the Magisterium published it’s official version? (Please see the Decrees of Vatican I, Session 3, Ch. 2, Sections 8 & 9)

2. Reply: Protestant commentaries can also describe how passages were interpreted historically and what the differences are, Joseph. I can get that anywhere. I want what you are selling – a singular, identifiable, “authoritative”, Magisterial interpretation that tells me which one is the right one. I mean after all, that’s what we’re talking about, right?

Joseph, I can’t recall what you are studying but I do wish you the best in your endeavors. But think with me about this scenario. You walk into class on your first day. At the front of the room is your professor who introduces himself as the authority on the topic you will be studying. He then explains that he has only really, definitively explored a “miniscule portion” of the coursework ahead but most of it will come to you through “common sense”. Would you be inclined to say he is going to be a “good” teacher?

Be well and until next time……

Paul,

Thanks truly for the response. It may seem like it sometimes, but I am not just trying to be combative (though I get frustrated, too). I can at least see better where you’re coming from now.

As I’m sure you know, Paul, I am an historian by training. I do not think I am guilty of this. If anything, I feel my outlook on the Church is colored more by the Church Fathers than anything modern. I am certainly biased, but I do not think I am biased in the way you charge. (I also do not think, as I’ve argued to my Traditionalist Catholic brethren, that there is any essential “rupture” being Vatican II and all the rest of Tradition. As you yourself said, all later councils, including Vatican II, have affirmed Trent.)

I could say exactly the same thing to you.

Per the word itself, as I’m sure you know, “Magisterium” means “teaching authority.” I do not know what specifically you are complaining about with regard to the cases you name (you’ll have to be more specific), but at least one of them (the Papal States) has nothing at all to do with the “teaching authority” of the Church and is not even relevant to this conversation. The others, in so far as I’m aware, do fall legitimately within the “teaching authority” of the Church. A teacher is not a dictator, but a good teacher does sometimes dictate and discipline, and has the authority to do so.

My translation of Vatican I (Vincent McNabb, New York: Benzinger, 1907) reads:

This, I’m sure you realize, is basically a verbatim quote from Trent, from the very passage I previously examined. And it answers your question directly: this “true sense” can be found where the Fathers of the Church agree and where the teachings of the Church over the ages have been timeless and consistent.

You will have to cite a specific case, since I don’t know of any. But in general I would say that an ecumenical council, one consisting of a body of worldwide bishops in communion with the See of Peter, is bound to be the higher authority. Not everything a pope says or does is even intended to be authoritative.

To my knowledge, the only time the authority of popes and councils have ever been in apparent conflict was the Western Schism, when it wasn’t entirely clear who was the pope. This is hardly a case that can be generalized, and even that case was sorted out through time, deliberation, and prayer.

I use the term “common sense” to refer to something that is shared in common. That is not the same thing as saying such a thing is “innate,” as the term “common sense” is often understood in other usages. As I said above in several places, that “sense” is guided and formed by the teachings of Magisterium (not independent of it): It may be shared by well-catechized Catholics, but only because they have been well catechized.

Is your interpretation of Scripture “independent” of Calvin or the other Reformers?

Sure, but in the sense of “private interpretation” I used above: one in accord with the sense of the Church, not “independent” of it.

Haven’t we beat this dead horse enough? (And here, I think you are heckling me.) The charge is simply untrue. (1) If one could read in the Middle Ages, one could read Latin. (2) If one could read Latin in Europe in the Middle Ages, one could gain access to a Bible. (3) If one could not read Latin in Europe in the Middle Ages or gain access to a Bible, then the stories, teachings, and parables of the Bible were richly illustrated in public art in churches for the benefit of the common people. (4) All of the earliest vernacular translations of the Scriptures were enacted by Catholics, not Protestants. Should I continue? If you are going to continue with this empty accusation, you should be prepared to provide some evidence to support it.

Yes; yes it is. The most recent Catechism, which cites that verse a number of times, is a good place to start:

To my knowledge, there has never been a conflicting teaching of the Magisterium (that is, one taught authoritatively by ecumenical councils or popes) with regard to this verse. Do not confuse the opinions of various Church Fathers or of divergent modern prelates with “claims of Rome.”

I did not say “consult many”; I said “consult any” (from the many from which you have to choose). These are guides to the teachings of the Church, since no, beyond the Catechism, the Church does not issue a compendium of those teachings. The Church’s teachings are scattered among thousands of documents; if you want to consult each of them, you’re welcome to make a lifetime of that. Most of us, thourgh, make use of commentaries and guides. You asked where you could find the Church’s authoritative interpretations of Scripture; this was the answer to your question.

Where there is confusion about a passage, yes, you can find authoritative guidance and teaching from the Church. But you still seem to be expecting the Church to be a dictator, to tell you exactly what to think and understand on every single point. And no, that isn’t what I’m selling, as I’ve been trying to make clear all along.

I never said that the authority in question had only “definitely explored a ‘miniscule portion'”: But just because one has not written an encyclopaedic compendium giving authoritative answers to every single point of knowledge does not mean she doesn’t have those answers or the authority to give them. The role of a teacher is not to dictate or lord her authority over her students: it is to teach them the sense to learn and read for themselves. She does not, either, hand them the source material and then leave them to their own devices (that seems to be the position of Protestants).

The peace of the Lord be with you.

Hello,

Thank you for this profound reflection on Jesus’ authoritative teaching in Mark 1:21–28. Your analysis illuminates how Christ’s words astonished His listeners—not merely through eloquence, but through an intrinsic authority that contrasted sharply with the scribes’ reliance on external sources. This distinction underscores the unique nature of Jesus’ ministry and His embodiment of divine truth. Your insights serve as a compelling reminder of the transformative power of authentic, divinely inspired teaching.