(This is a post I made earlier this year which seems appropriate for the solemnity of All Saints, updated and revised for the occasion and expanded with some better explanations, since I’ve learned and grown a lot since the original post.)

It occurred to me the other morning in the shower (that’s where thoughts usually occur to me) that many Protestants might be troubled by the concept of saints and sainthood. I have heard Protestants say, “We don’t believe in saints.” I assure you that you do. Do you believe that there are people in Heaven? Then you believe in saints.

A saint, very simply — in the sense that the Roman Catholic Church (and the Eastern Orthodox Church) declares one a saint, and grants “Saint” as a title — is someone whom we believe, with certainty, is in Heaven with God. That’s all. From Latin sanctus (Greek ἁγιος or hagios), the word means “holy, sacred, set apart.” In biblical usage, as Protestants should be aware, “saints” refers to all the “holy ones,” the believers of the Church. When we state in the Apostles’ Creed that we believe in the “communion of saints,” we are saying that we believe all believers, both those who are living and those who have died, are a part of our Body and share in our communion with Christ. The author of the Epistle to the Hebrews envisions in the Old Testament saints and prophets a “great cloud of witnesses” surrounding us (playing on μαρτυρέω, testify, bear witness, in Hebrews 11:39, and μάρτυρες, witnesses [also the same word as martyrs], in Hebrews 12:1), evoking the image of spectators in an arena as we “run . . . the race that is set before us.” How much more would those who die in Christ join this “cloud”!

Veneration, not Worship

Catholics venerate saints — we respect, honor, and revere them; we celebrate their memory — because of their great witness and example for us in faith, virtue, and godliness. They are the heroes of the faith whose godly lives we want to remember and whom we want to emulate. They are our spiritual ancestors, our predecessors, our loved ones, the members of our family who have gone to their reward, and yet are still with us in communion with Christ. We do not worship the saints; only God is worthy of worship. We venerate them in much the same way Americans venerate the memory of George Washington or Abraham Lincoln.

Along the same lines: as much as Catholics are accused of “worshipping” the Virgin Mary, let me set the record straight: we don’t. We venerate Mary in the same way we venerate the saints, for she is one, too. For all that we speak of her being mother to the Church and to all Christians, she is one of us: a human person, a Christian — the first Christian — the firstfruits of salvation, who shows forth to us all that we are promised in Christ. Loving and honoring Mary is just a way to love and worship Jesus all the more.

The Intercession of Saints

So why do Catholics pray to saints? Well, if we believe that they too are part of our communion in Christ, a “great cloud of witnesses,” then why should we be separated from them? They are our friends and family, our brothers and sisters in the Lord who have crossed the river before us. They are already by Christ’s side. Why shouldn’t they pray for us? And aren’t they in a better position for that, to bring our needs and requests before God? Catholics believe that the saints can intercede for us. Praying to saints is nothing more than asking our loved ones to pray for us.

Patron Saints

So what is the deal with patron saints? Well, just as the saints had particular interests and causes and affinities when they were here on earth, they do in Heaven too. A saint is held to be the patron (Latin patronus, protector, defender, advocate, patron — yes, like in Harry Potter) of the profession, activity, nation, cause, or place with which they were associated in earthly life. He or she is held to be a patron against specific diseases, afflictions, and dangers when, through suffering or death, they have gained victory over those things in Christ. And, through tradition, through practice, through trial and error, saints are held to be the patrons of these things because their intercession proves efficacious: because prayers for their aid in those causes work. Saints don’t have magical powers. Saints don’t, in themselves, produce effects on this earth. But by where they are and whom they’re with, they have immense spiritual power to intercede on our behalf.

Relics: What they leave behind

So what about relics? Why the macabre obsession with dead body parts? You may or may not be aware that in most Catholic altars there is a relic of some saint (Latin relictum, that which is left behind or remaining) — usually a small piece of bone or some other body part, but sometimes the whole body, or possibly an object the saint owned or touched. We hold that the person, his or her spirit, is in Heaven with Christ — but that the things which the saint left behind, his physical body most of all, offers a connection, an anchor, a bridge to their presence in that spiritual realm. The idea of placing relics under our altars — or building our churches and altars over their remains, as in the cases of Saint Peter and Saint Paul and many other ancient saints — is that by proximity to these connections, by association with these saints, we can draw as near to Heaven and to God as possible.

The Cleansing Fire of Purgatory

Another thing: Aren’t all Christians who die saints? We do believe that all Christians who die in the grace of God will go to Heaven, yes; but we Catholics also believe in Purgatory — which is not what you might think it is. It is not a place like Heaven or Hell (an idea Dante made popular) but a process. It does not detract from Christ’s victory over sin on the Cross, from His salvation or from His forgiveness of our sins. Everyone who experiences Purgatory has already had his or her sins forgiven, paid in full; he or she will be saved and is promised eternity in Heaven.

But it is the calling of every Christian to take part in the life of Christ’s grace, to live within His Church and Sacraments, to pursue holiness and grace and daily be sanctified and converted (Latin converto, turn towards, change, transform) to Christ’s image. To put it in the terms of Protestant theology: According to Luther and Calvin, justification, the forensic declaration that one is holy and righteous before God, by which Christ’s righteousness is imputed to the believer, is different than sanctification, the process by which the believer is actually made holy and righteous, by living and working in God’s grace. (Catholics believe these are part of the same process.)

Nothing unholy or impure can enter Heaven — so for those of us believers who are not able to finish this process of sanctification, of being transformed, in our lifetimes on earth — and this will be most of us — there is Purgatory, a fire in which we will be purified of our faults and shortcomings and made holy and pure, ready to stand before God (1 Corinthians 3:15, 1 Peter 1:7). If anything, the fire of Purgatory is not a detraction from Christ’s sacrifice, but its fulfillment: He has paid the penalty for our sins, the death we deserve. Purgatory is a tool of His mercy by which even those of us believers who struggle with sin, who are less than perfect, can be saved.

Canonization

Saints, on the other hand, are very special people who, through life in God’s grace, did achieve holiness and become wholly molded to Christ’s image in this life, to the extent that they could as fallen creatures. (Cf. the Wesleyan idea of entire sanctification.) They are people whose godliness is not in doubt, people like the Apostles and St. Francis and St. Thérèse. These days, there are so many very godly people dying that there is a formal process of canonizaton in the Church, through which a person’s sainthood is confirmed and verified, as best as we on Earth can: by asking them for intercession and seeing if those prayers are answered. Two or three miracles associated with a saint’s intercession is the usual standard. A martyr’s death is the saint’s golden ticket to immediate canonization: they pay the price in blood.

Protestant Saints

Are there Protestant saints? You can bet there are. Just because someone hasn’t been formally declared a saint by the Church doesn’t mean they’re not one. Walk through any cemetery, and there are likely to be unknown saints lying all around, people who led truly godly lives and who merited Christ’s reward as soon as they crossed over from this life. Catholics are never in the business of declaring who isn’t or who can’t be saved, or who isn’t or can’t be saints: we believe God, in his infinite mercy, grants His grace and His favor according to His own will.

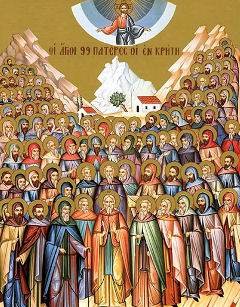

All Saints and All Souls

So what are the holidays that the Roman Catholic Church celebrates on November 1 — All Saints’ Day (or All Hallows’, the origin of Halloween, or Hallows’ Eve) — and November 2 — All Souls’ Day? Well, in the 2,000 years of Church history, there have been a lot of saints, a lot more than the few who get their own universal feast days on the liturgical calendar that are celebrated by the whole Church. There are even more saints who are unknown: everyday holy people who have been sanctified but never attract the attention or veneration of the Church. All Saints’ Day — the Solemnity of All Saints — is the day the Church celebrates all the saints — the many who don’t get celebrated any other day.

All Souls is the other side of the picture: our beloved dead in Christ who may not have been wholly sanctified at the time of their passing. Officially called the Commemoration of All the Faithful Departed, it is the day dedicated to remembering them and praying for them, for mercy and grace in their purification and passing to Heaven. We believe that just as we on earth are in communion with the saints in Heaven, we are also in communion with our faithful departed who may not be there yet. We have no idea how long Purgatory takes — it may, as Pope Benedict has reasoned, not be measured in our time at all, but be an “existential” passage that happens in an instant by our reckoning — but we believe, as the Church has always believed, that our prayers for our departed brothers and sisters help them and ease their journey (2 Maccabees 12:46).

May all the saints pray for us, the Church on earth, and may all the souls of our beloved dead pass into the everlasting light!

I thought you bookended the discussion nicely, starting out with the “communion of saints” and the “cloud of witnesses” and ending with All Saints/Souls Days. Loved it 🙂 .

It’s always a a bit of a surprise to hear Christians who profess the faith with the Apostles’ Creed say that they don’t believe in saints. Of course, it doesn’t surprise me when the “No Creed But Christ” Christians say that, but that’s expected. Protestants are used to hearing the word Saint used in either New Orleans or only referring to the canonized Roman Catholic saints. They don’t always make the connection that those who have died before us ARE the saints.

It took me a long time to understand the intercession of the saints. I don’t agree with everything you wrote there, but I finally understood a few years ago that asking the dead to pray for us was no different than asking our living brothers and sisters to pray for us if we truly believed in the communion of saints. I don’t know if I’d assent to the canonized saints’ prayers being more resourceful than our own, but I can see that belief played out among the living too–people want priests and pastors to pray for them because in their minds, clergy have a “thing” with God that makes their prayers more valuable. I discourage that sort of belief through the priesthood of all believers.

As for Purgatory, Relics, Canonization, and Patron Saints, I don’t know if I’d necessarily say they’re wrong, but I’ve never seen the point. Relics would seem like magic, except we believe the same thing about bread, wine, and water, so I’ll have to mull that over in my mind.

Thanks. 🙂 I thought it worked out well. As I thought of this post in the first place in the shower (back in June), I thought of it again yesterday morning rolling out of bed.

St. John the Revelator, I’ve noticed, uses the word “saint” to refer to both the living and the dead in Christ. The Revelation gives a vivid picture of the saints in heaven offering up “the prayers of the saints” — all of them.

Yeah, I’m not an expert on intercession; I wrote my basic understanding, mostly informed by osmosis. Roman Catholics do believe in the idea of merit, which is often misunderstood as us saying that God shows favoritism on people because of our good works. But the Bible does say through and through that we will be rewarded according to our works; that those who do good works on earth store up treasure in heaven. And we remember that every good work we do is the fruit of God’s grace, no merit of our own. He gives us the talents; we go and use them wisely: and those who are faithful with a few things will be put in charge of many things. Protestantism likes to be democratic and level the field and say we are all the same in God’s eyes; that we are all sinners; no one is righteous, not one — but that’s not exactly a very biblical idea. All through the Bible there are people who are highly favored by God and given great rewards and responsibilities on earth. Why wouldn’t he continue to reward those who merit favor in heaven? It makes sense to me that the more righteous, the more highly favored, the more “clout” one effectively has — and the more powerful one’s prayers are. Certainly, as you say, we’d all consider it more likely to be efficacious to have the pope personally praying for us than the local layman.

Relics, and the medieval cult of relics, certainly were abused at times and led to “magical” thinking. But to me, it’s just another aspect of veneration. I’ve always been a bit of a hoarder (an “archivist,” I like to say). It means a lot to me to have items that belonged to my Granddaddy and other ancestors, or even from friends who have passed on. I love cemeteries more than almost anything on earth, and I definitely feel a connection — mostly emotional, but perhaps spiritual — with a loved one when I stand at their graves. I think the tendency to preserve relics of people and events is a universal impulse in one way or another. We put historical relics under protection and on display in museums — because they, in a way, give us a connection to the past. We talk in history about the “numinal” value of historic sites and relics. Saintly relics absolutely have numinal value. They inspire faith and veneration, give people a felt connection to beloved and holy people. That relics have real spiritual power is another matter, but there’s plenty of testimony of miracles and answered intercession that can’t all be dismissed as superstition.

Very informative, thank you.

Thank you. I’m glad to help. 🙂

Interesting that you mentioned Purgatory. Today our parish priest spend a notable amount of time teasing out the facts about Purgatory, and I think it’s the first time I ‘ve ever listened to a homily which devoted at least 10 minutes to the topic. It’s good to hear about Purgatory from the pulpit. It not only reveals our belief in this place of purging, but today made me contemplate more deeply on how simple we are as human beings and that in order for us to reach the side of our Maker, we must be cleansed through and through in order to be made ready to take our place in Eternity.

For some, they question Purgatory and it’s existence.

I’ve only been Catholic for not quite a year (I was pretending to be Catholic for a year or so before that) — but I’ve heard my pastor speak on it once or twice (not for 10 minutes). I think it’s clear enough that it has to exist, when we acknowledge that nothing sinful can stand before God and not be blown away. Even a Protestant admitted that to me the other day, that there has to be a cleansing first.

Hi, you said “no one is righteous, not one — but that’s not exactly a very biblical idea.” With all due respect, that is actually a quote from Psalm 14 and Romans 3:10. And it’s exactly why we all need Jesus. I don’t know what protestants say, just to be clear. I’m not trying to argue at all, please understand. Just pointing out that yes, it is a biblical idea. May God’s blessings be upon you and yours this Advent and Christmas. ♥️

Yes, of course it’s a quote. I was quoting it, too. But my point was, the Scriptures are full of people who are called righteous, and of righteousness spoken of as something that can be attained. So why seize on the Psalmist’s clearly hyperbolic statement — my Bible says “there is none that does good” — as an absolute repudiation of all goodness and righteousness? That is indeed how Protestants, especially those of the Calvinist ilk, do take such statements, that there literally is “no one who does good,” that “all our righteousness is filthy rags” (Isa 64:6), etc. Absolutely, yes, every one of us needs God’s grace and salvation, and

without Him we can do nothing” (John 15:5). But it is not a biblical idea to insist that humans are incapable of doing any good at all. His peace and grace be with you!