[I outlined this post a few Saturdays ago but got busy and didn’t finish it. It refers to the day’s prayers at Mass. For the record, they are from Saturday, March 18.]

Growing up as a Pentecostal youth, pretty much the sum of my Christian experience was in waiting for, proclaiming, or savoring the presence and working of the Holy Spirit. High-powered, emotional worship services were all about experiencing the Holy Spirit through ecstatic detachment, “getting lost” in Jesus. I’ve written before about how this emotional experience of God was difficult to maintain, especially for a teen who struggled with depression and anxiety, and how ultimately it lacked a lot of substance in terms of real commitment or intellectual depth. It was about momentary excitement and stimulation, but after the emotion was passed, this didn’t always amount to a real change.

Whether it lasted or not, core to my faith in God was the belief that Holy Spirit is immanent in the Church and in our lives; that He works in us and through us daily; that He moves in us powerfully, inspires us, changes us, heals us. I believed in miracles, both in wondrous physical healing and in changed lives through spiritual transformation.

None of this faith was lost when I became Catholic. Though it’s true I’ve grown more skeptical of the sensational and the ecstatic, I still believe that the Holy Spirit is at work in us and in the Church, and that He has the power to change us and to heal us. I’ve often heard the complaint that the liturgical approach to experiencing God feels regimented, constricted, and limiting; that it “quenches the Holy Spirit” and does not allow Him to work; that unless we are free to “get lost” in worship, we are not giving God the freedom to move in us.

This couldn’t be further from the truth. Though at times it may seem, as it did to me early in my journey to Catholicism, that Catholic practice marginalizes the Holy Spirit or downplays His work (I once suggested here that Catholicism made the Holy Spirit a “tag-along”), in fact the Holy Spirit is absolutely central to everything the Church does and Christians do, to all our prayer and all our liturgy, to every work of God’s grace that we do and that God does in us, most of all to the Sacraments.

Come, Holy Spirit

A key difference that I observe between the Catholic approach to the Holy Spirit and the Pentecostal or Charismatic one is that the Catholic approach to the Holy Spirit is introspective, focused on the work of the Holy Spirit in us, while the Charismatic approach tends to focus on outward signs and manifestations. This is evident in the very ways in which we invoke the Holy Spirit. Charismatics very often speak of the Holy Spirit “filling this place” like an atmosphere, or “feeling the Holy Spirit here” as something external, as “the presence of God.” A popular song implores:

Holy Spirit, You are welcome here

Come flood this place and fill the atmosphere

Your glory, God, is what our hearts long for

To be overcome by Your presence, Lord

The presence of the Holy Spirit, for the Charismatic, is about “God showing up and showing out” — as I often heard. It is something that manifests itself most of all in a show of power and wondrous signs; something that overpowers the senses and overcomes the person.

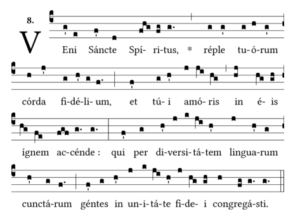

The differences in the Catholic view can be seen in our own hymn, Veni, Sancte Spiritus (“Come, Holy Spirit”):

Veni, Sancte Spiritus,

et emitte caelitus

lucis tuae radium.Come, Holy Spirit,

send forth the heavenly

radiance of your light.O lux beatissima,

reple cordis intima

tuorum fidelium.O most blessed light,

fill the inmost heart

of your faithful.Lava quod est sordidum,

riga quod est aridum,

sana quod est saucium.Cleanse that which is unclean,

water that which is dry,

heal that which is wounded.Flecte quod est rigidum,

fove quod est frigidum,

rege quod est devium.Bend that which is inflexible,

fire that which is chilled,

correct what goes astray.Da tuis fidelibus,

in te confidentibus,

sacrum septenarium.Give to your faithful,

those who trust in you,

the sevenfold gifts.

For the Catholic, the coming of the Holy Spirit is not so much about “filling this place” as about “filling our hearts“; not about outward displays or manifestations so much as about inward sanctification, healing, and transformation.

The Holy Spirit in the Sacraments

The essential ground of the Holy Spirit is the Sacraments. When I was first becoming Catholic, I was so accustomed to looking for the Holy Spirit in outward signs and wonders that I mistook that He was missing or absent from Catholic life altogether. Far from being absent, the Holy Spirit is the Spirit of God on the earth, and is present in the Church, in everything we do, and most of all in us. In each of the Sacraments, God works in our lives and communicates His grace to us through the Holy Spirit.

The essential ground of the Holy Spirit is the Sacraments. When I was first becoming Catholic, I was so accustomed to looking for the Holy Spirit in outward signs and wonders that I mistook that He was missing or absent from Catholic life altogether. Far from being absent, the Holy Spirit is the Spirit of God on the earth, and is present in the Church, in everything we do, and most of all in us. In each of the Sacraments, God works in our lives and communicates His grace to us through the Holy Spirit.

In Baptism, we are “born of water and the Spirit” (John 3:5-7); we are washed, regenerated, and renewed (Titus 3:5) — and the agent is the Holy Spirit. In the sacrament of Confession, it is the Holy Spirit Himself who forgives our sins and accomplishes the same cleansing (1 John 1:9). And most powerfully and intimately in the Eucharist, it is the Holy Spirit who makes present the reality of Christ’s Body and Blood in His Paschal mystery. I was struck today by how the Mass’s prayer after Communion highlights the work of the Holy Spirit in us:

May your divine Sacrament, O Lord, which we have received,

fill the inner depths of our heart

and, by its working mightily within us,

make us partakers of its grace.

Through Christ our Lord.

In a real way, both physically and spiritually, the Sacrament fills us — but it is the Holy Spirit Who through it, fills the innermost depths of our heart and works mightily within us. I don’t think I had made this connection before, between the reality of the Lord’s Presence in the Eucharist and the presence of the Holy Spirit as worker. But certainly I had always felt this innately.

From the very first time I received the Lord in the Eucharist — and every time since — I have felt this powerfully and viscerally: the Lord Himself working powerfully in my heart, more intimately than I had ever experienced before — an overpowering sense of being touched, inhabited, seized from within. This working is transformative: Coming to the Sacrament from the greatest places of darkness and despair, it has never failed to bring light to my heart; from the deepest hurt, it has brought healing and restoration; from the brink of the greatest temptation, it has brought strength and respite; even from moments or boredom, disinterest, and not wanting to be there, it has brought, unexpected and unlooked for, a renewed focus and friendship with the Lord. In the truest sense, I am overcome by the Lord’s presence in the Eucharist, in my encounter with Him.

Jesus worked His miracles through physical touch, visiting His people in the flesh and impacting their lives by direct and physical interaction. He gave us the Eucharist using the same physical language of encounter: “I am the living bread which came down from heaven; if any one eats of this bread, he will live for ever; and the bread which I shall give for the life of the world is my flesh.” (John 6:51) As He invited sinners throughout his earthly ministry, He invites us to sup with Him and share a meal with Him (Revelation 3:20). After He ascended bodily to Heaven, and sent His Holy Spirit to be our Paraclete, He nonetheless left us with the possibility, in that meal and through the Spirit, of such an intimate encounter with Him. As He touched us physically during His earthly ministry, through His Body and Blood in the Eucharist, he continues to touch us physically in the most intimate communion, and through that touch to work powerfully in our hearts and spirits. The Sacraments are the means by which the Holy Spirit enters, is poured into our lives. He literally fills us and transforms us.

Jesus worked His miracles through physical touch, visiting His people in the flesh and impacting their lives by direct and physical interaction. He gave us the Eucharist using the same physical language of encounter: “I am the living bread which came down from heaven; if any one eats of this bread, he will live for ever; and the bread which I shall give for the life of the world is my flesh.” (John 6:51) As He invited sinners throughout his earthly ministry, He invites us to sup with Him and share a meal with Him (Revelation 3:20). After He ascended bodily to Heaven, and sent His Holy Spirit to be our Paraclete, He nonetheless left us with the possibility, in that meal and through the Spirit, of such an intimate encounter with Him. As He touched us physically during His earthly ministry, through His Body and Blood in the Eucharist, he continues to touch us physically in the most intimate communion, and through that touch to work powerfully in our hearts and spirits. The Sacraments are the means by which the Holy Spirit enters, is poured into our lives. He literally fills us and transforms us.

Key to Protestant misunderstandings

It occurs to me that understanding of the Holy Spirit’s central role in the Sacraments is the key to several Protestant misunderstandings. Of the Eucharist in particular, it is easy for the mind to trip over the physical claims about the real presence of the Lord, when the truth is not one of material at all but of encounter and indwelling, concepts Protestants readily understand in speaking of the Holy Spirit.

Even more important, Protestants routinely charge that Catholic claims about receiving grace through the Sacraments amounts to a system of “works’ righteousness,” that somehow we are subjecting the reception of grace to what we do or to human working. It is only in the understanding that each of the Sacraments is solely the work of the Holy Spirit, given to us in grace, that this myth can be dispelled. Where is the “human work”? In requiring that we do something? Humans need only be there, to receive the grace. In placing the Sacraments at the hands of a priest? The priest is only a servant, a vessel, a tool; it is only the Holy Spirit who accomplishes the work. Is it in making grace about something more than “faith alone”? It is only the most radical misreading of Paul that presumes even the Sacraments of the Church to be “works done by us in righteousness” (Titus 3:5, which is one of the most explicit references in Scripture to the efficacy of Baptism as “the bath of regeneration” by the Holy Spirit). In neither the views of Jesus or of Paul does “faith” exclude action: Jesus asks His listeners to step out in faith in order to receive their healing (e.g. Matthew 9:20-22; Mark 10:46-52; Luke 17:11-19; John 9:1-7); Paul, as above, holds forth sacramental means of grace (et. e.g. Colossians 2:12; Romans 6:3-6; Galatians 3:27) rather than a bare “faith alone” — which threatens, as much as any charge against Catholics of “works’ righteousness” to make grace subject to the action of the person (having faith) rather than the working of the Holy Spirit.

The Holy Spirit is the glue of our faith: In a Trinitarian sense, neither the Father nor the Son, but the Spirit of God that proceeds from both. He is the medium of grace, the means, the actor and worker in our lives and in the Church, by which we are filled, renewed, healed, and transformed. It is in the Holy Spirit that we are bound to God and to each other in communion. The Holy Spirit is the Spirit of God on earth, the person through whom we encounter God and Christ — and that encounter, the place of our God entering our lives and working in our hearts, is most viscerally and tangibly in the Sacraments.

You must be a lot younger than I am. These type of “let the Holy Spirit fill this place” didn’t really come into being on a large scale until the 1990s. And that thanks mostly to Benny Hinn, and Kathryn Kuhlman before him. It was nothing being done by say, Billy Graham, the most well-known evangelist in the world, and the one who brought the most people to Christ due to the nexus of radio, TV and stadiums being built.

Billy Graham, it should be pointed out, has never been a Pentecostal; Kathryn Kuhlman was and Benny Hinn is. Kuhlman was active in the 1970s and these tendencies have been present in the Pentecostal wing of Christianity for a very long time — if not inherent to it, looking back to its origin at Azusa Street.

I grew up in an Assemblies of God church in the 80s and 90s. In my early childhood it tended more toward “traditional” Pentecostalism, though my church was fairly progressive even for that. It always tended toward emotionalism, though, and toward viewing the Holy Spirit as I’ve described. I think a lot of this sort of talk and attitude became mainstream to Evangelicalism through popular worship music like that of Hillsong and others.

Thanks for the comment.

I stumbled across your blog while I was researching Confirmation for a post I’m writing. Can I link to this post (or others) as a “further reading”? Thanks!

Welcome, and thanks! Yes, please do! God bless you!