I’ve been asked to defend the Catholic belief that Peter was the first pope. This article is in response to my friend Raymond the Brave's assertions and to the article he posted, which in turn is a re-posting from the site “Ex-Catholics for Christ.” Below I’ve attempted to address this question as comprehensively as possible, and address fully and honestly the contrary evidence provided. I hope to correct some common misconceptions regarding how the Catholic Church has historically understood the papacy and Peter’s role in founding it, and to provide convincing answers to many common Protestant challenges. I hope also to demonstrate, with full quotations, that many of the common texts that opponents cite from Scripture and the Church Fathers against the papacy are excerpted inappropriately out of their proper contexts — which in many cases, shown in the full context, refute the very argument they are trying to make.

All Scripture quotations, unless otherwise noted, are from the Revised Standard Version, Catholic Edition (RSVCE).

Outline

- Misunderstanding the Question: What is the Papacy?

- Why does the question matter?

- Who is the pope?

- What authority did Jesus give the Apostles?

- Was Peter the leader of the Apostles?

- Did Jesus give Peter a primacy of authority among the Apostles?

- Did Peter act as leader of the Apostles?

- Was Peter a bishop?

- Was Peter in Rome?

- More than one Bishop?

- One bishop (monoepiscopacy)

- Apostolic succession in Scripture

- Apostolic succession in the early Church

- Did Peter’s primacy of authority extend to his successors?

- Development of the Papacy

- Has the succession of bishops of Rome been unbroken?

- Final objections

- Final conclusion

Misunderstanding the Question: What is the Papacy?

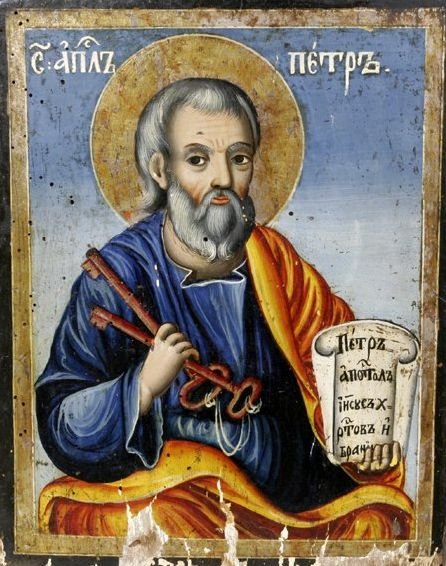

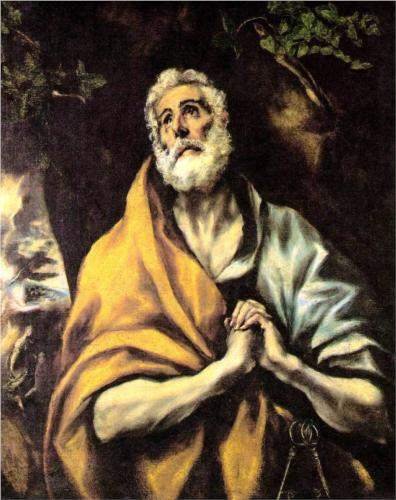

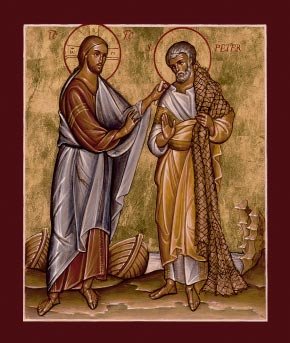

Was Peter the first pope? It seems a basic enough question, one that most Protestants are raised up to reject with a knee-jerk. The idea of the Apostle Peter of the New Testament, the simple fisherman, the man too humble to allow Jesus to wash his feet (John 13:8), adorned with the lavish trappings of the modern papacy, the jewelled tiara, the sumptuous vestments, speaking from an elevated throne — seems utterly ridiculous. But to dismiss the question at that does the truth a great injustice: for this is not what the Catholic Church claims.

The fundamental problem that many Protestants struggle with in understanding the papacy is that they project a modern understanding of that office onto the first-century Church. Was Peter the first pope, with the same understanding of that office, the same traditions, the same external trappings, as modern popes such as Pope John Paul II, Pope Benedict XVI, and Pope Francis? No, probably not. But what does the Catholic Church understand the papacy to be? The author of our original post bandies about such words as “tyranny” and “dictatorship” — and it’s true that in the past, there have been holders of the papal office who were wont to abuses of wealth or temporal power. But what, fundamentally is the papacy? Why does the office exist? The Catholic Church believes that Jesus appointed Peter as the pastor of His entire flock on earth (cf. John 21:15–18), and since He did not intend to leave his people as sheep without a shepherd (Mark 6:34), intended for this unique role of Peter to extend to men who would follow in his footsteps.

So when we ask, “Was Peter the first pope?” the question we are really asking is, “Did Jesus appoint Peter to a special pastoral role in His Church?” We will attempt to answer this question from Scripture. Secondarily, we will ask whether this role was meant to continue to others after Peter’s death.

Why Does the Question Matter?

Was Peter really the first pope? The author of the original article asks:

Before we answer this historical question students of the Bible and church history should be encouraged to ask, why would certain “ecclesiastical parties” want everyone to give an affirmative yes to this question?

It is a basic question: why should anyone care? Why should the Catholic Church teach such a doctrine, and expect others to accept it? Why should I devote so much of my time and so many words to supporting this idea? Why should it matter, especially to Protestants, whether a man who lived two thousand years ago held or didn’t hold any particular office?

The most basic answer I can give: Because as Christians, we should seek the truth. If it is true what the Catholic Church claims — if Jesus appointed the Apostle Peter the pastor over His flock, and intended that pastorship to be carried on by Peter’s successors — then every Christian, as a member of Jesus’s flock, should follow His appointed shepherd.

Our author offers a different answer to this question:

Because if this can be substantiated and unequivocally be found in Scripture, then it might give the pope of Rome his dictatorial and tyrannical authority, which he has enjoyed for many centuries.

But this reflects the misunderstanding addressed above. In answering the question of whether Jesus appointed Peter and his successors pastors of His Church, we should put aside the thought of “dictatorial” and “tyrannical” abuses over the ages, and approach first the early centuries of the Church. We should ask more basic questions: Is the idea of Peter as pastor of the whole Church scripturally sound? Is this what the earliest Christians understood? For the question of whether the papacy has been corrupted over the centuries is foreign to the original question, “Was Peter the first pope?”

Why would Jesus appoint a pastor of His universal Church? Many Protestants have a problem with the idea of Jesus founding the Church as One Body (1 Corinthians 10:17) and appointing a single leader over it; and yet as I will demonstrate below, Scripture strongly indicates that in Peter, he did just that. And speaking generally, the reasons for appointing a pastor — or shepherd — are three: for guidance, for protection, and for unity.

A shepherd guides his flock on straight paths, and leads them toward the pasture of the goal. He looks out for his sheep, that they do not go astray, and tends to their needs. He also protects his sheep from danger, from attackers, from pitfalls, from their own wanderings. And he keeps his sheep together in one flock, for their safety and for their good, that all of them may reach their promised land.

Jesus is our Good Shepherd. He promised that “there [would] be one flock, one shepherd” (John 10:16). And yet in the years since the Protestant Reformation, any sense of unity under a single shepherd has been lost in Protestant Christianity. There are today more than 40,000 distinct Protestant denominations, most of which can agree together on little more than the basic, historic tenets of Christianity, if even on that. False doctrine, heresy, and schism rock and rend churches daily and lead countless sheep astray. Today, when even basic Christian mores are eroding away, the need for guidance, protection, and unity in the Body of Christ is greater than ever before.

And yet the Catholic Church claims, and has held since the earliest times, that Jesus provided us with just such a shepherd in the person of the Apostle Peter. The prophet Jeremiah foresaw that God would “give [us] pastors according to [His] own heart, and they shall feed [us] with knowledge and doctrine” (Jeremiah 3:15, Douay-Rheims Bible [hereafter DR]). Ezekiel foretold that the people of God “[would] have one shepherd” (Ezekiel 37:24, DR), a promise of the coming Messiah. And yet these prophecies referred to earthly leadership, the return of an earthly kingdom. And our Lord is with us always — but where is our earthly shepherd? Could it be without meaning, in the light of all these promises, that Jesus charged Peter to “shepherd His sheep” (John 21:15–18)?

If it is true that the Catholic Church is the “one, holy, catholic and apostolic Church” founded by Jesus, and it is true that He appointed Peter as that Church’s pastor, then we all who follow the Lord have an obligation to heed the guidance of His anointed shepherd, and seek a return to unity with the rest of the one flock of God. If it is true that the pope is the pastor of all Christians, then Jesus desires us all to be held in the arms of “one flock, one shepherd.”

Who is the “Pope”?

If one is going to reject Catholic claims, one must first understand what the Catholic Church actually claims — else one is only rejecting a straw man and a caricature. As we have argued above, the central question when we ask whether Peter was the first pope is whether Jesus appointed Peter as the pastor over His one flock. But then, why do we ask if he was the “pope”? What is this title, where did it come from, and why do we use it today?

Who is the “pope”? The original article purports to demonstrate that Peter was not the first pope, but what is the Catholic Church actually claiming when she says that Peter was the first pope? We readily acknowledge that Peter would probably not have recognized the title “pope” during his lifetime. The term “pope” — Latin papa or Greek παππάς (pappas), meaning “papa,” an affectionate term for “father” — was originally applied, in the East, to any priest, and in the West, to any bishop*, as can be found in the letters of St. Cyprian of Carthage, whom even the Roman clergy addressed as “blessed papa” (cf. Epistle II in Ante-Nicene Fathers, vol. 5). But over the centuries, the term came to be applied in the West exclusively as an honorific title for one man: the bishop of Rome.

The pope is the bishop of Rome. The primacy and authority that the Catholic Church claims the pope holds rests not in the title “pope,” but in his office as bishop of Rome and successor of Peter. So the more appropriate question to ask is not “Was Peter called the ‘pope’?” but “Was Peter the bishop of Rome?” But we must build up this: we must first answer other questions: Did Jesus give Peter a role of primacy among the Apostles? Was Peter in Rome, and if he was, did he hold the office of bishop? And if he did, did the authority that he held extend to his successors in that office?

* Our author in fact acknowledges this:

One must also appreciate that from the third to the tenth century, all Catholic bishops were addressed as pope or papa. Even today, Italians still call the pope, “papa.”

So, the bishop of Rome was called the pope … and yet he wasn’t the pope?

What Authority Did Jesus Give the Apostles?

For these first questions, we may turn to the most authoritative of our evidence: to Scripture itself, the written Word of God. And even more basically than whether Peter held a primacy of authority among the Apostles, let us first ask: What authority did Jesus give to the Apostles in general, and what was the nature of that authority?

I have already addressed this question in another post to some extent. Here, let me summarize:

- He gave them the authority to do what He did: “And He called to Him His twelve disciples and gave them authority over unclean spirits, to cast them out, and to heal every disease and every infirmity” (Matthew 10:1) — the authority to perform miraculous signs and wonders in His name.

- He gave them the authority to speak in His name: “He who hears you hears Me, and he who rejects you rejects Me, and he who rejects Me rejects Him Who sent Me” (Luke 10:16).

- He gave them the authority to be His representatives: “He who receives you receives Me, and he who receives Me receives Him Who sent Me” (Matthew 10:40).

- He gave them the authority to celebrate the Eucharist in remembrance of Him: And he took bread, and when he had given thanks he broke it and gave it to them, saying, “This is my body which is given for you. Do this in remembrance of me.”

(Luke 22:19) - He assigned them a kingdom: “You are those who have continued with me in my trials; and I assign to you, as my Father assigned to me, a kingdom, that you may eat and drink at my table in my kingdom, and sit on thrones judging the twelve tribes of Israel” (Luke 22:28–30). This again implies a grant to the Apostles of some authority from on high, that which the Father had assigned Jesus, to rule and to judge.

- He gave them the authority to bind and loose in heaven and on earth: “Truly, I say to you, whatever you bind on earth shall be bound in heaven, and whatever you loose on earth shall be loosed in heaven” (Matthew 18:18). What does this mean? According to the Jewish Encyclopedia [1], “binding and loosing” were rabbinical terms that meant to make binding and authoritative doctrinal and disciplinary pronouncements in the assembly, to pronounce or revoke an anathema upon a person, and by the authority of Jesus, to forgive or to retain sins (cf. John 20:23). It was the “power and authority, vested in the rabbinical body of each age or in the Sanhedrin, that received its ratification and final sanction from the celestial court of justice.” Even many Protestant scholars support this definition (see Johannes Wilhelm Kunze, “The Power of the Keys,” in S.M. Johnson, C.C. Sherman, and G.W. Gilmore, eds., The New Schaff-Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge [New York and London: Funk and Wagnalls, 1908], vol. VI: 323–329).

- He sent them in His parting from this earth to go and teach with authority: “All authority in heaven and on earth has been given to me. Go therefore and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit…” (Matthew 28:18–19) It is because (“therefore”) all authority had been given to Jesus that the Apostles had the authority to go and do everything He did.

With this understanding of apostolic authority in mind, let us now turn to the question of whether Peter was the leader of the Apostles.

Was Peter the Leader of the Apostles?

It is often claimed (and not just by Catholics) that Peter was the “chief apostle” or the “leader” of the Apostles. Is this true? All four Evangelists (that is, Gospel-writers) seem to have thought so. In the Gospel accounts, where most of the other Apostles appear as supporting characters, it is indisputable that Peter had a major role. In all four accounts combined, if the number of mentions by name each Apostle received is tabulated, Peter’s prominence is unrivaled:

| Simon Peter (Cephas) | 100+ times* |

| James son of Zebedee | 17 times |

| John son of Zebedee | 17 times |

| Philip | 14 times |

| Andrew | 11 times |

| Thomas (Didymus) | 10 times |

| Bartholomew (Nathanael) | 9 times |

| Matthew (Levi) | 7 times |

| James son of Alphaeus | 4 times |

| Judas (Thaddaeus) | 4 times |

| Simon (the Zealot or Cananaean) | 3 times |

| Judas Iscariot | 20 times |

* This is an unscientific count, done by the number of times the names appear in a word search of the Gospels, picking out the times those names refer to someone else (e.g. John the Baptist, Simon of Cyrene, James son of Alphaeus). Counting the Book of Acts, Peter appears an additional 55 times, John son of Zebedee 9 times, James son of Zebedee twice, the other James four times, and no other of the Twelve more than once.

The Gospel of Matthew refers to Simon Peter as the πρῶτος (prōtos) disciple, the “first” (Matthew 10:2); in every named list of the Twelve in Matthew, Mark, Luke, and Acts, Peter is listed first (Matthew 10:2, Mark 3:16, Luke 6:14, Acts 1:13), despite not having been the first called (cf. John 1:40–42). Peter is most often the disciple to speak or interact personally with our Lord (e.g. Matthew 14:28–33, 15:15–20, 17:1–4, 18:21; Mark 8:29–33, 11:21; Luke 5:8, 9:20, 24:14; John 13:6–11, 13:36–38, 18:10–11), often speaking for the rest (e.g. Matthew 19:27, Mark 9:5, 10:28; Luke 8:45, 9:33, 12:41, 18:28; John 6:68) or approached by outsiders as the leader of the band (e.g. Matthew 17:24).

All the Apostles, it would seem, abandoned Jesus in the immediate hours after His arrest in Gethsemane, but it is only Peter who is presented as having insisted upon his faithfulness to the Lord beforehand, and it is only Peter whose denial is explicitly foretold and focused upon. In all four Gospels, upon Jesus’s arrest, the perspective then shifts — the “camera” follows Peter and not any other of the Twelve (Matthew 26:69–75, Mark 14:66–72; Luke 22:55–62; John 18:16–18, 25–27). It is likewise only Peter whom John the Evangelist, after the Resurrection, sets apart to highlight his reinstatement by Jesus and His forgiveness for his denial (John 21:15–19).

Paul, too, sets Peter apart from the rest of the Twelve:

And he appeared to Cephas, then to the twelve. (1 Corinthians 15:5)

Finally, following Jesus’s Resurrection, the angels themselves set Peter apart as someone standing ahead of the rest of the Apostles, addressing the women:

But go, tell his disciples and Peter that he is going before you to Galilee; there you will see him, as he told you” (Mark 16:7).

It would seem apparent, then, that by the testimony of the Evangelists themselves, Peter was the foremost and the leader of the Apostles. But was this merely because of his prominence, his outspokenness, a dominant personality or a quick tongue? — or did Jesus appoint Peter leader of the apostolic band? Did Jesus give Peter a primacy of authority among the Apostles?

Did Jesus Give Peter a Primacy of Authority among the Apostles?

First, what is it that we mean by primacy? Primacy means the first place or foremost position. A primacy of authority does not mean an “absolute” or “dictatorial” rule: merely that this is an authority that stands ahead of the rest. Jesus gave the above apostolic authority to each of the Apostles. Did He give Peter any extraordinary place over and beyond what He gave the rest?

“And on this rock I will build My Church”

It is apparent that He did, on at least several occasions. In the most commonly cited passage, Jesus sets Peter apart with a triple blessing:

And Jesus answered him, “Blessed are you, Simon Bar-Jona! For flesh and blood has not revealed this to you, but my Father who is in heaven. And I tell you, you are Peter, and on this rock I will build my Church, and the gates of Hades shall not prevail against it. I will give you the keys of the kingdom of heaven, and whatever you bind on earth shall be bound in heaven, and whatever you loose on earth shall be loosed in heaven.” (Matthew 16:17–19)

Now, I have already written about this passage at greater length than I can here, delving more deeply into an exegesis of the Greek (see “On This Rock: An Analysis of Matthew 16:18 in the Greek”). But let me here address a few claims of the above article:

Rome believes that there are Aramaic and Hebrew manuscripts for the New Testament. However, if this is true, then they are as elusive as Iraq’s weapon of mass destruction, for no scholar, religious or secular, has ever found one fragment.

This is, in fact, not something that the Catholic Church believes or claims. The source of this misstatement is probably a quotation from Irenaeus of Lyon (c. A.D. 180), who stated:

Matthew also issued a written Gospel among the Hebrews in their own dialect, while Peter and Paul were preaching at Rome, and laying the foundations of the Church. (Against Heresies III.1.1)

Now, it is plain to everybody that the Gospel of Matthew that is now extant is not in Hebrew or Aramaic, but in Greek. Nonetheless, many of the Church Fathers, following Irenaeus, have believed that Matthew’s Gospel was originally written in Aramaic and later translated into Greek, the Aramaic original no longer surviving. Whether this is true or not is a matter for textual scholars, and is not really relevant to the question at hand.

What is plain, and nearly universally recognized, is that Jesus did not speak Greek, but Aramaic. In the Gospels, the Evangelists, especially Mark, record a number of memorable Aramaic words and phrases which our Lord uttered among us, quoting His actual words in His original tongue, for special emphasis or dramatic effect: for example, “Talitha cumi” (Mark 5:41), “Ephphatha” (Mark 7:34), “Abba, Father” (Mark 14:36), “Eloi, Eloi, lema sabachthani?” (Mark 15:34). So regarding the author’s claim:

Now on the surface it all appears rather simple. The Lord makes Peter the church on which He will build on. But when one reads the whole Bible, problems soon occur. First, the Greek word for Peter is petros, meaning a small stone. Second the Greek word for rock is petra, meaning a large stone.

First of all, this claim, often cited among Protestants, is untrue. πέτρος and πέτρα did not, in fact, mean a “small stone” and a “large stone.” While in classical Greek, there may have been some distinction between the meanings of the two words, that distinction was never between “small” and “large,” but between a massive, unmovable rock (πέτρα) and stone as a monumental building material, similarly unmovable (πέτρος). By the first century A.D. when the Gospels were written, the words were generally used interchangeably (cf. e.g. Rev. Caleb Clark [a Protestant pastor], “Exposition of Matthew 16.18,” in The Biblical Repository and Classical Review, third series, no. 3 [July 1845], LIX:413–421, at 417).

Second, as I have pointed out before, the grammatical rules of Greek required that Peter’s name (which, by the writing of the Gospels, had been his name in Greek for decades) be the masculine Πέτρος; yet Jesus in this passage is comparing Peter and his statement of faith to the πέτρα, the rock upon which they were standing. The way the passage is rendered in Greek is the only way it could have been rendered to maintain the wordplay — called paronomasia, a common rhetorical device in Greek — and any Greek listener would have understood it that way. Even most knowledgeable Protestant scholars of Greek recognize this (cf. [1], [2], [3], [4], etc.).

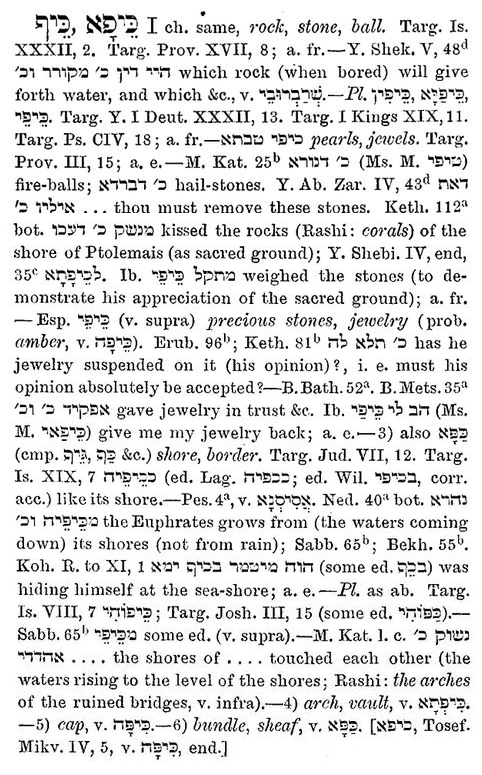

Third and most important: in the Aramaic language that Jesus spoke, the words for “Peter” and “rock” were one and the same: Kepha (כיפא). John the Evangelist (John 1:42) and the Apostle Paul (1 Corinthians 15:5, Galatians 1:18) both acknowledge that this is what the Lord actually called Peter in His own tongue (not “Peter”) by their transliteration of Peter’s name as Cephas. When Jesus made the pronouncement of Matthew 16:18 in Aramaic, He would have used the same word twice: You are Kepha, and on this kepha I will build My Church.

Concerning John 1:42, our author makes the claim:

Please also note that in John 1:42, Jesus calls Peter “a” stone. Not “the” stone.

I’m not sure to what he is referring (apparently the King James Version of the text?). The Greek of that verse (N.B. That link is an English interlinear that you can follow along with) most literally reads:

He brought him to Jesus. Jesus looked at him and said, “You are Simon the son of John; you shall be called Cephas” (which is translated Peter) (John 1:42, NASB).

Our author further claims:

Some may also be interested to learn that the meaning of the Aramaic word for Peter (Cephas) is sand. Not the best foundation to build upon.

In fact, this is untrue. Did our author not just now acknowledge that in calling him “Cephas,” Jesus called Peter “a stone”? Kepha means a rock or stone, as Marcus Jastrow’s Dictionary of Targumim, Talmud, and Midrashic Literature (London: Luzac; New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1903) informs us:

I would prefer to think that our author has made a mistake and is not acting in bad faith here. Perhaps he thinks a “shore” is made of “sand,” and generalizes from that? But no, most shores in the world are made of rock, as this word plainly means — as Peter (Πέτρος) means in the Greek, and John himself confirms (“Cephas … means Petros,” John 1:42).

So it would appear that a careful play on words has just taken place. Jesus is not making Peter the church/rock, but rather He is the Rock Himself, with Peter being a small stone.

Indeed, a careful play on words has taken place. No, Jesus has not made Peter “the Rock” or “the Church,” but He has proclaimed that Peter is a rock suitable to be a foundation for His Church. Yes, Jesus alone can be said to be the Rock, but as Paul tells us elsewhere:

So then you are no longer strangers and sojourners, but you are fellow citizens with the saints and members of the household of God, built upon the foundation of the apostles and prophets, Christ Jesus himself being the cornerstone, in whom the whole structure is joined together and grows into a holy temple in the Lord; in whom you also are built into it for a dwelling place of God in the Spirit (Ephesians 2:19–22).

But at last, putting aside all of this needless quibbling over words: it really is irrelevant. No matter how one interprets Jesus’s proclamation to Peter in Matthew 16:17–19, the indisputable fact is that Jesus set Peter apart from the other Apostles and imparted blessings to him alone. In response to Peter’s singular confession of Jesus as Christ — and using singular pronouns and verbs, and otherwise parallel grammar — Jesus addressed Peter alone to give three separate blessings:

- You (Peter) are “Rock,” and on this rock I will build My Church, and the gates of hades shall not prevail against it.

- I will give you (Peter) the keys of the kingdom of heaven [mirroring “the gates of hell”].

- Whatever you (Peter) bind on earth shall be bound in heaven, and whatever you loose on earth shall be loosed in heaven [linked implicitly to the “keys”].

“I will give you the keys of the kingdom”

And in fact, not only is this impartation of the keys given directly to Peter alone, but this proclamation is a direct reference to Old Testament prophecy, whose context makes absolutely clear what is taking place here:

Thus says the Lord GOD of hosts, “Come, go to this steward, to Shebna, who is over the household, and say to him: … I will thrust you from your office, and you will be cast down from your station. In that day I will call my servant Eliakim the son of Hilkiah, and I will clothe him with your robe, and will bind your girdle on him, and will commit your authority to his hand; and he shall be a father to the inhabitants of Jerusalem and to the house of Judah. And I will place on his shoulder the key of the house of David; he shall open, and none shall shut; and he shall shut, and none shall open. And I will fasten him like a peg in a sure place, and he will become a throne of honor to his father’s house (Isaiah 22:15, 19–23).

The imagery of opening and shutting by means of the key to the gates of the house of David is directly evoked by Jesus’s language of binding and loosing by means of the keys to the gates of the kingdom of heaven in such a way that what is bound on earth will be bound in heaven, and what is loosed on earth will be loosed in heaven. Even many Protestant exegetes widely acknowledge the reference of Matthew 16:19 to this passage — cf. the New American Standard Bible (NASB), English Standard Version (ESV), and the Cambridge Paragraph Bible of the Authorized English Version (ed. F.H. Scrivener, 1873), all of which include Isaiah 22:22 as a cross-reference; and this fascinating reference I found in my Logos collection:

The key figuratively depicts the responsibility of a position and the power to make decisions in that position — i.e., to open and close doors. So to place the key on someone’s shoulder denotes giving that person the power and responsibility of a certain position. In our text-verse (Isaiah 22:22), Shebna, the treasurer of Hezekiah, is warned that Eliakim will carry “the key to the house of David.” This is a figurative way of expressing what was already said in the 21st verse: “I will … hand your authority over to him.”

The idea contained in both these passages is expressed in Isaiah 9:6, where it is said of the Messiah: “the government will be on his shoulders.” The word keys is used figuratively again when Jesus says to Peter: “I will give you the keys of the kingdom of heaven; whatever you bind on earth will be bound in heaven, and whatever you loose on earth will be loosed in heaven” (Matthew 16:19). (“Isaiah 22:22: Key on Shoulder” in James M. Freeman and Harold J. Chadwick, The New Manners & Customs of the Bible [North Brunswick, NJ: Bridge-Logos Publishers, 1998], 355).

In fact, the HALOT translates the word סֹּכֵ֣ן (soken) — translated steward in the RSVCE and ESV and treasurer in the KJV, as an administrator, the overseer of the house of the king, the highest official in the kingdom. In this context, it demonstrates a clear grant of messianic authority (a government that would otherwise be on the Messiah’s shoulder) to a deputy or servant who would rule over the kingdom in the king’s absence. That this position would become a throne bears the implication of a successive office, one to be carried forward by appointed successors. And most strikingly, this official would be called a father to the inhabitants of the kingdom — a spine-tingling evocation of what this office, to the successors of Peter, would in fact be called: papa, or father.

Some Objections

Here it may be expedient to address several objections our friend has raised regarding our Lord’s actions toward Peter in the Gospels.

James and John were given special places of position with Jesus in the future Kingdom, yet Peter wasn’t consulted once nor did Jesus refer them to him.

I am confused by this objection. This claim seems inconsistent with the Gospel accounts on several different points. In neither of the accounts of requests for special positions for the sons of Zebedee does Jesus respond favorably. Also, in both accounts “the ten” (including Peter) are onlookers to the request, and are “indignant at the brothers.” In Mark’s Gospel James and John ask:

And James and John, the sons of Zebedee, came forward to him, and said to him, “Teacher, we want you to do for us whatever we ask of you.” And he said to them, “What do you want me to do for you?” And they said to him, “Grant us to sit, one at your right hand and one at your left, in your glory.” But Jesus said to them, “You do not know what you are asking. Are you able to drink the cup that I drink, or to be baptized with the baptism with which I am baptized?” And they said to him, “We are able.” And Jesus said to them, “The cup that I drink you will drink; and with the baptism with which I am baptized, you will be baptized; but to sit at my right hand or at my left is not mine to grant, but it is for those for whom it has been prepared.” And when the ten heard it, they began to be indignant at James and John. (Mark 10:35–41)

In a nearly identical account in Matthew’s Gospel, it is their mother who asks (Matthew 20:20–24).

Our friend also raises:

We also read in John’s Gospel, how certain Greeks went to Philip to have him introduce them to Jesus. Philip then went to Andrew (not Peter) to speak with Jesus.

I don’t recall it ever being claimed that Peter was Jesus’s personal secretary, or the gatekeeper through whom all interaction with our Lord had to take place. In the passage in question:

Now among those who went up to worship at the feast were some Greeks. So these came to Philip, who was from Bethsaida in Galilee, and asked him, “Sir, we wish to see Jesus.” Philip went and told Andrew; Andrew and Philip went and told Jesus (John 12:20–22).

This seems to have been a case of mere convenience, of whomever was nearest to the Lord at the moment bringing Him the message.

Why wasn’t Peter the first to see the resurrected Christ?

Because the women were? Apparently, though, Peter was next:

And they rose that same hour and returned to Jerusalem. And they found the eleven and those who were with them gathered together, saying, “The Lord has risen indeed, and has appeared to Simon!” Then they told what had happened on the road, and how he was known to them in the breaking of the bread (Luke 24:33–35).

Our friend again:

And at the end of this Gospel, Peter is rebuked by Jesus again, but this time for asking what John’s future fate would be.

I didn’t remember this “rebuke,” so I looked again:

When Peter saw him, he said to Jesus, “Lord, what about this man?” Jesus said to him, “If it is my will that he remain until I come, what is that to you? Follow me!” The saying spread abroad among the brethren that this disciple was not to die; yet Jesus did not say to him that he was not to die, but, “If it is my will that he remain until I come, what is that to you?” (John 21:21–23)

This doesn’t come across as a “rebuke” to me. In any case, whoever said Peter was above rebuke (see below)?

If anybody is to be considered as “Papal” material, it would not be Peter (a man who tried to kill Malchus, deny Jesus three times and preach a false gospel in Gal. 2) but Paul the Apostle. Yet even he was more modest and humble than most modern-day preachers are, whether Protestant or Catholic.

Whoever said Peter, or any of the Apostles, or any one of us, was of “material” to be what God called us to be, before He worked in our lives? Was Peter of the “material” to be an Apostle at all, a rough and uneducated fisherman and a “sinful man” (Luke 5:8)? God took Peter, even in all his flaws and failings and “little faith,” and made a mighty man of God of him; and in him we see ourselves, and all His grace to us, and have hope that He can use us, too. This argument presumes that God only calls us because of some merits of our own — but such is clearly not the case — thank God.

“Strengthen your brethren”

In another, less often cited passage, a dispute has broken out among the Apostles at the Last Supper, about “who was to be regarded as the greatest” — certainly a question of import to this discussion. In this context, Jesus commands his disciples concerning the principle of servant leadership:

A dispute also arose among them, which of them was to be regarded as the greatest. And he said to them, “The kings of the Gentiles exercise lordship over them; and those in authority over them are called benefactors. But not so with you; rather let the greatest among you become as the youngest, and the leader as one who serves. For which is the greater, one who sits at table, or one who serves? Is it not the one who sits at table? But I am among you as one who serves. (Luke 22:24–27)

Opponents of the papacy and of church hierarchy in general often point to these statements as evidence that there were to be no authoritative leaders among the group; but Jesus says quite the opposite: “Let the greatest among you become as the youngest, and the leader as one who serves.” The clear implication is that there will be one who is greatest — who will become as the youngest — and there will be a leader — who will be one who serves.

Jesus continues, as quoted above:

“You [all] are those who have continued with me in my trials; and I assign to you [all], as my Father assigned to me, a kingdom, that you may eat and drink at my table in my kingdom, and sit on thrones judging the twelve tribes of Israel.” (Luke 22:28–30)

Addressing the group in the plural, Jesus assigns to each of the Apostles an authoritative role, a throne in His coming kingdom.

But then, in His very next statement, He singles Peter out:

“Simon, Simon, behold, Satan demanded to have you, that he might sift you like wheat, but I have prayed for you that your faith may not fail; and when you have turned again, strengthen your brethren” (Luke 22:31–32).

Even among the Twelve, whom He has just said will each sit on thrones in His kingdom, Peter must stand out as a leader, who must strengthen [his] brethren during the coming trial. In the very same statement, in the very next verses, Jesus singles out Peter again — to prophesy that he would deny Him.

And he said to him, “Lord, I am ready to go with you to prison and to death.” He said, “I tell you, Peter, the cock will not crow this day, until you three times deny that you know me” (Luke 22:33–3).

Peter especially, even above the rest of the disciples, would be put to the test (Luke 22:40) — because “to whom much is given, of him will much be required; and of him to whom men commit much they will demand the more” (Luke 12:48).

“Feed my sheep”

For all the quibbling that can be made over Matthew 16:17–19, perhaps the clearest and most important statement of the authority that Jesus entrusted to Peter occurs in John 22, at Peter’s reinstatement. Jesus takes Peter aside, in the presence of the other other Apostles, and speaks to him:

When they had finished breakfast, Jesus said to Simon Peter, “Simon, son of John, do you love me more than these?”

The only “these” to whom Jesus could be referring are the other Apostles. Why should it be of any consequence that Peter love the Lord more than these, unless he was to stand out among them in a special role?

He said to him, “Yes, Lord; you know that I love you.” He said to him, “Feed my lambs.” A second time he said to him, “Simon, son of John, do you love me?” He said to him, “Yes, Lord; you know that I love you.” He said to him, “Tend my sheep.” He said to him the third time, “Simon, son of John, do you love me?” Peter was grieved because he said to him the third time, “Do you love me?” And he said to him, “Lord, you know everything; you know that I love you.” Jesus said to him, “Feed my sheep.” (John 21:15–18)

For each of the three times Peter denied Jesus, Jesus asks Peter if he loves Him; and three times He commands Peter to “tend His sheep.” And Jesus in fact uses two different words here in the Greek for “feed” and “tend,” which are indicative of what it is He is asking Peter to do. The first time and the third time He asks him to “Βόσκε (boske) His lambs,” meaning to tend to the needs of animals, herd, tend, or especially to feed. But the second time He asks him to “ποίμαινε (poimaine) His sheep,” meaning to serve as tender of sheep, herd, tend, lead to pasture, and particularly when applied to people, to watch out for other people, to shepherd — or to pastor. This verb is commonly applied, in both the New Testament and the Old Testament Septuagint, to the pastoring of the flock of Christ. From this same word is ποιμήν (poimēn), the word for shepherd or pastor (cf. Ephesians 4:11), derived.

When David was anointed king of Israel, the Septuagint uses this verb:

“You shall be shepherd (ποιμήν) of my people Israel, and you shall be prince over Israel” (2 Samuel 5:2).

In the prophecy of Jeremiah, the Septuagint voices these words:

And I will give you shepherds (ποιμένας) after my own heart, who will feed (ποιμανοῦσιν) you with knowledge and understanding (Jeremiah 3:15)

This messianic prophecy declares not only a single shepherd — for surely Jesus is our Good Shepherd (John 10:11–18) — but an order of shepherds keeping the Lord’s flock. And most compellingly, in Peter’s own epistle, he applies this same verb in his exhortations to his “fellow presbyters”:

So I exhort the presbyters among you, as a fellow presbyter and a witness of the sufferings of Christ as well as a partaker in the glory that is to be revealed. Tend (ποιμάνατε) the flock of God that is your charge, not by constraint but willingly, not for shameful gain but eagerly, not as domineering over those in your charge but being examples to the flock. And when the chief Shepherd (ἀρχιποίμενος, lit. arch-shepherd) is manifested you will obtain the unfading crown of glory (1 Peter 5:1–4)

Just as the Lord charged Peter to shepherd His flock, Peter exhorts his brother presbyters, by the same authority, to shepherd the flock of God that is in your charge. Very plainly then, the role to which Jesus especially appointed Peter, among his fellow Apostles and the whole flock of God, was a pastoral one.

Did Peter Act as Leader of the Apostles?

So if we believe that Jesus entrusted to Peter a primacy of authority ahead of the rest of the apostolic band, we next need to ask: Do we find Peter exercising such leadership?

In fact, very clearly, we do. In addition to the plainly preeminent role Peter played in the Gospels, we find him, from the very beginnings of the Church on earth, assuming the charge over the flock which Jesus had given him:

In those days Peter stood up among the brethren (the company of persons was in all about a hundred and twenty), and said, “Brethren, the scripture had to be fulfilled, which the Holy Spirit spoke beforehand by the mouth of David, concerning Judas who was guide to those who arrested Jesus. For he was numbered among us, and was allotted his share in this ministry … (Acts 1:15–17).

Here, presiding over the flock in the upper room, Peter takes the initiative, led by prophecy and the Holy Spirit, of choosing a successor for the fallen Judas Iscariot. And then, on the day of Pentecost, it is Peter alone who stands up for the Twelve, who receives the verbal inspiration of the Holy Spirit, who speaks for Christ and preaches the first proclamation of Jesus’s Resurrection and salvation, leading more than three thousand into the kingdom (Acts 2:14–41). Some time later, it is Peter who heeds the prompting of the a Spirit to offer healing to the beggar at the Gate Beautiful, and brings forth another bold sermon to the people (Acts 3:1–4) and a ready defense before the Sadducees and high priests (Acts 4:5–22). One can draw no other conclusion from these passages that that Peter was divinely used by God in a role of leadership in the early Church through the Holy Spirit.

We next see Peter acting for the Church, as the administrator of the Church’s finances, in the case of Ananias and Sapphira (Acts 5:1–11). As more and more believers were added to the Lord, it is Peter to whom the people gather and cling as if he were the representative of Christ Himself:

And more than ever believers were added to the Lord, multitudes both of men and women, so that they even carried out the sick into the streets, and laid them on beds and pallets, that as Peter came by at least his shadow might fall on some of them. (Acts 5:14–15)

It was to Peter alone that the Lord gave the revelation that salvation was for Gentiles as well as Jews; and he brought the Gospel to the household of Cornelius (Acts 10). Peter opened his mouth and said: “Truly I perceive that God shows no partiality, but in every nation any one who fears him and does what is right is acceptable to him” (Acts 10:34–35). When Peter was criticized by the circumcision party, he recounted these events: “And I remembered the word of the Lord, how he said, ‘John baptized with water, but you shall be baptized with the Holy Spirit.’ If then God gave the same gift to them as he gave to us when we believed in the Lord Jesus Christ, who was I that I could withstand God?” (Acts 11:16–17) And when they heard his testimony, they ceased their dissent immediately: “they were silenced; and they glorified God” (Acts 11:18).

Peter in the second half of the Acts of the Apostles

Peter was very plainly the leader of the Church in these early chapters of Acts — mentioned by name, as cited above, some 55 times, to the other Apostles who, besides John, hardly get a second mention. Some opponents seek to make much of the fact that in the latter half of the book, Paul eclipses Peter as the dominant character in the narrative. But this is to be expected, since Luke, the author, was a known companion of Paul (cf. Colossians 4:14, 2 Timothy 4:11, Philemon 24). Indeed, at several points Luke’s account shifts into the second person: he seems to have been an eyewitness to the events (e.g. Acts 16:10–18, 20:5–16, 21:1–18, etc.)

So what became of Peter? Our friend seeks to make several arguments concerning Peter’s decline from prominence in Acts. In Chapter 8, he points out:

“Now when the apostles which were at Jerusalem heard that Samaria had received the word of God, they sent unto them Peter and John: Who, when they were come down, prayed for them, that they might receive the Holy Ghost” (8:14,15). Here the church sent Peter and John. Peter didn’t send himself.

Along these same lines, in Chapter 9:

“But Barnabas took him [Paul], and brought him to the apostles, and declared unto them how he had seen the Lord in the way, and that he had spoken to him, and how he had preached boldly at Damascus in the name of Jesus” (9:27). Again the apostles are spoken of as a group, not one person in total command.

Our friend seems to misunderstand what is being claimed by saying Peter had primacy. No one supposes that Peter was a one-man-show or a dictator, or even the only leader in the Church. Peter was one Apostle among Twelve, among other presbyters and deacons in the Church, who met and loved and shared together. But just as he was during Jesus’s earthly ministry, Peter was recognized to be the foremost.

In Chapter 12:

About that time Herod the king laid violent hands upon some who belonged to the church. He killed James the brother of John with the sword; and when he saw that it pleased the Jews, he proceeded to arrest Peter also. This was during the days of Unleavened Bread. And when he had seized him, he put him in prison, and delivered him to four squads of soldiers to guard him, intending after the Passover to bring him out to the people. So Peter was kept in prison; but earnest prayer for him was made to God by the church. (Acts 12:1–5)

Our friend asks:

Interesting to note that James, the brother of John … was chosen BEFORE Peter to be killed. If Peter was “supreme” why not go for him first?

This seems a strange argument. Why was Stephen “chosen” before any Christian to be killed (Acts 7)? Are we meant to gather from this that Stephen was the most important early Christian? Stephen was “chosen” because he was outstanding and outspoken, because “full of grace and power, [he was doing] great wonders and signs among the people” (Acts 6:8); he threatened the status quo and angered the ruling parties, and so was persecuted. Above all, he was “chosen” because God chose him to become a martyr for the faith. Such was also the case for James the Greater: being a “Son of Thunder” (Mark 3:17), he no doubt was also bold and outstanding, with a quick tongue and a quick temper: he angered Herod; he got caught; and God rewarded him with a martyr’s crown. That was God’s plan for James. But God had other plans for Peter, a mission yet to fulfil.

Following the death of James and Peter’s arrest, Peter was visited by an angel, who miraculously freed him from prison (Acts 12:6–19). As Peter was escaping:

He went to the house of Mary, the mother of John whose other name was Mark, where many were gathered together and were praying. And when he knocked at the door of the gateway, a maid named Rhoda came to answer. Recognizing Peter’s voice, in her joy she did not open the gate but ran in and told that Peter was standing at the gate. They said to her, “You are mad.” But she insisted that it was so. They said, “It is his angel!” But Peter continued knocking; and when they opened, they saw him and were amazed. But motioning to them with his hand to be silent, he described to them how the Lord had brought him out of the prison. And he said, “Tell this to James and to the brethren.” Then he departed and went to another place. (Acts 12:12–17)

Here our friend argues:

Upon Peter’s escape from prison he calls for James and then the brethren to be made aware of his safety. James was clearly the main leader in Jerusalem.

This too seems a strange argument, given Peter’s indubitable prominence up until this point in the book — and the fact that this is only the second time that the other James has been mentioned at all — or, if you accept the Protestant argument, that this James is not the same as the other James who was among the Twelve (cf. Acts 1:13), his very first, passing mention.

No, it would appear rather that James was Peter’s deputy, another leader in the Church who would have stepped forward in Peter’s absence. And in fact, this is in keeping with the early traditions of the Church of Jerusalem: For after Peter “departed and went to another place” (i.e. he departed from Jerusalem), James the Just was chosen bishop of Jerusalem. According to tradition, Peter was also the first bishop of Antioch (cf. Galatians 2:11, Apostolic Constitutions VII.46; Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History III.36.2) before founding the Church at Rome; it is possible that that he went either to Antioch or to Rome at this time. Wherever he went, it is all the more fitting that Peter should have contacted James before his departure.

The Council of Jerusalem

We now come to the one of the most pivotal events in Acts: the Council of Jerusalem, which would resolve the growing dispute between the Apostles and the Judaizers, or “circumcision party” (cf. Acts 11:2), over the question of whether Gentile Christians should be required to be circumcised and to observe the Law of Moses.

In Galatians 2, one of the earliest of Paul’s epistles (c. A.D. 54), Paul describes a contentious confrontation concerning this issue between himself and Peter, James, other leaders of the Church of Jerusalem. Scholars have differing opinions about how this event relates to the council recorded in Acts 15, of an apparently more congenial nature:

And from those who were reputed to be something (what they were makes no difference to me; God shows no partiality)—those, I say, who were of repute added nothing to me; but on the contrary, when they saw that I had been entrusted with the gospel to the uncircumcised, just as Peter had been entrusted with the gospel to the circumcised (for he who worked through Peter for the mission to the circumcised worked through me also for the Gentiles), and when they perceived the grace that was given to me, James and Cephas and John, who were reputed to be pillars, gave to me and Barnabas the right hand of fellowship, that we should go to the Gentiles and they to the circumcised; only they would have us remember the poor, which very thing I was eager to do. (Galatians 2:6–10)

But our friend raises several questions about this. He asks:

Why is it that James, the Lord’s half brother, is mentioned before Peter in superiority in Galatians 2:9?

I fail to see how the position of James’s name in a sentence implies any sort of “superiority,” especially when Peter has already been mentioned earlier in the sentence, and Peter, James, and John are all acknowledged as “men who were reputed to be pillars.”

Continuing with the passage:

But when Cephas came to Antioch I opposed him to his face, because he stood condemned. For before certain men came from James, he ate with the Gentiles; but when they came he drew back and separated himself, fearing the circumcision party. And with him the rest of the Jews acted insincerely, so that even Barnabas was carried away by their insincerity. But when I saw that they were not straightforward about the truth of the gospel, I said to Cephas before them all, “If you, though a Jew, live like a Gentile and not like a Jew, how can you compel the Gentiles to live like Jews?” (Galatians 2:11–14)

Our friend asks:

Why did Paul have to rebuke Peter in front of the entire church?

Paul answers this question for himself: “because he stood condemned” — in other words, because he was wrong. No one ever claimed that Peter was perfect; in fact, he was one of the most human, and humble, of the Apostles. No argument for Peter’s primacy supposes that Peter couldn’t be wrong or didn’t make mistakes or was beyond reproof.

Now we come to the account of the Council of Jerusalem itself. First, the council is gathered:

But some men came down from Judea and were teaching the brethren, “Unless you are circumcised according to the custom of Moses, you cannot be saved.” And when Paul and Barnabas had no small dissension and debate with them, Paul and Barnabas and some of the others were appointed to go up to Jerusalem to the apostles and the presbyters about this question. So, being sent on their way by the church, they passed through both Phoenicia and Samaria, reporting the conversion of the Gentiles, and they gave great joy to all the brethren. When they came to Jerusalem, they were welcomed by the church and the apostles and the presbyters, and they declared all that God had done with them. But some believers who belonged to the party of the Pharisees rose up, and said, “It is necessary to circumcise them, and to charge them to keep the law of Moses.” (Acts 15:1–5)

Our friend asks:

Here is the first church conference in Scripture and we note how the church sent Paul and Barnabas on their way. They didn’t go up on their own authority. They were sent.

I don’t really understand what point our friend is trying to make. Yes, Paul and Barnabas did not go on their own authority; they were sent by the Church, apparently at Antioch (cf. Acts 14:26–28, 15:35), along with “some of the others.” This is an official, authoritative council of the Church that is taking place; every church was to send representatives.

The apostles and the presbyters were gathered together to consider this matter. And after there had been much debate, Peter stood up and said to them, “Brothers, you know that in the early days God made a choice among you, that by my mouth the Gentiles should hear the word of the gospel and believe. And God, who knows the heart, bore witness to them, by giving them the Holy Spirit just as he did to us, and he made no distinction between us and them, having cleansed their hearts by faith. Now, therefore, why are you putting God to the test by placing a yoke on the neck of the disciples that neither our fathers nor we have been able to bear? But we believe that we will be saved through the grace of the Lord Jesus, just as they will.”

And all the assembly fell silent, and they listened to Barnabas and Paul as they related what signs and wonders God had done through them among the Gentiles. (Acts 15:6–12, ESV)

I have heard opponents claim that Peter “didn’t seem to be in a position of authority” at the Council of Jerusalem — but it is quite apparent that he was. It was only after there had been much debate that Peter stood up and spoke; and after his pronouncement, all the assembly fell silent. How can this be understood apart from the fact that Peter spoke with authority, and the council heard his words and heeded them?

Our friend next asks:

Why is it that [Peter] doesn’t close the church’s first meeting in Acts 15, but James does?

Returning to the scriptural account:

After they finished speaking, James replied, “Brothers, listen to me. Simeon has related how God first visited the Gentiles, to take from them a people for his name. And with this the words of the prophets agree, just as it is written …. Therefore my judgment is that we should not trouble those of the Gentiles who turn to God, but should write to them to abstain from the things polluted by idols, and from sexual immorality, and from what has been strangled, and from blood.” (Acts 15:13–15, 19–20)

As we have discussed above, James was appointed bishop of Jerusalem following Peter’s departure (Acts 12:17). If he “closed” the council, it was because the council met under his see and jurisdiction; he was the one presiding, the speaker and moderator, directing the proceedings of the council. This does not indicate that James’s authority extended beyond his own diocese or over any of the gathered bishops or representatives. The key point to note here is that James’s “judgment” is the opinion of Peter — it was Peter’s authority that carried the day.

It is evident, then, that from the dawning moments of the Church at Pentecost, forward through the Council of Jerusalem and beyond, Peter held a position of prime authority in the Church. What was the nature of that authority? Certainly Peter was an Apostle, one who was “sent,” but arguments for the papacy rest on Peter’s having been a bishop. Let us now ask whether Peter was, in fact, a bishop.

Was Peter a Bishop?

In fact, this is a simple question to answer from Scripture. The office of bishop — Greek ἐπίσκοπος (episkopos), Latin episcopus, of which the word “bishop” is a direct cognate in English — meaning “overseer” (ἐπί “over” + σκοπος “seer” [cf. scope]) — was not plainly defined in Scripture until Paul’s first epistle to Timothy (1 Timothy 3); but we find, from the opening chapter of Acts, that Peter describes the office of Apostle as one of oversight (ἐπισκοπή [episkopē]):

In those days Peter stood up among the brethren, and said, “Brethren, the scripture had to be fulfilled, which the Holy Spirit spoke beforehand by the mouth of David, concerning Judas who was guide to those who arrested Jesus. For he was numbered among us, and was allotted his share in this ministry. For it is written in the book of Psalms, ‘Let his habitation become desolate, and let there be no one to live in it’; and ‘His office (ἐπισκοπή) let another take.’” (Acts 1:15–17, 20–21)

As the Church spread, the Apostles appointed leaders wherever they went. New offices were soon established, those of presbyter and bishop. As Paul writes to Titus:

This is why I left you in Crete, that you might amend what was defective, and appoint presbyters in every town as I directed you. (Titus 1:5)

Presbyters — Greek πρεσβύτεροι (presbyteroi) — were literally “elders.” But it is evident from Paul’s comments here that in the very early days of the Church, the offices of presbyter and bishop were roughly synonymous:

For a bishop, as God’s steward, must be blameless; he must not be arrogant or quick-tempered or a drunkard or violent or greedy for gain…. (Titus 1:7)

And Peter, writing around the same time (A.D. 60s), informs us that he is a presbyter:

So I exhort the presbyters among you, as a fellow presbyter and a witness of the sufferings of Christ as well as a partaker in the glory that is to be revealed. (1 Peter 5:1)

As we have seen above, Peter exhorted his “fellow presbyters” to “pastor the flock of God”. But there is more, slipping through the verbal cracks of some recent translations:

Shepherd the flock of God among you, exercising oversight (ἐπισκοποῦντες) not under compulsion, but voluntarily, according to the will of God; and not for sordid gain, but with eagerness; nor yet as lording it over those allotted to your charge, but proving to be examples to the flock. (1 Peter 5:2–3, NASB)

Peter instructs presbyters to exercise oversight — ἐπισκοποῦντες (episkopountes), the participial form of the word ἐπίσκοπος (episkopos). In other words, he instructs them to be bishops (“overseers”).

So yes, by his own declaration, Peter was a bishop.

Was Peter in Rome?

But was Peter in Rome? Our friend alleges, as many opponents do, that Peter was never in Rome. The reason, they say, is that they cannot find it in Scripture. But this, I would suggest, is “sola scriptura” run amok. Whatever arguments may be made regarding sola scriptura and church doctrine, the fact is that Peter was a real, historical person who existed outside the pages of Scripture. Just as there were many other things Jesus did that were not recorded in Scripture (John 21:25), there are no doubt many things that Peter and the other Apostles did that are not recorded in these writings.

Most Protestants acknowledge as much. I have frequently heard even Protestants relate the traditions regarding the martyrdoms of Peter and the other Apostles — that Peter was crucified upside down, by his request, deeming himself unworthy to suffer in the same way as his Lord. But if they accept this story, they have no grounds for rejecting the claim — present in this same story (for Peter is said to have been crucified in Nero’s circus) — that Peter died in Rome.

The Scriptural Argument

The fact is, however, that Scripture strongly supports Peter’s having been in Rome. I have written at length on this matter before (see “Biblical Testimony to St. Peter’s Ministry and Death in Rome”), so here I will summarize.

Peter writes us, in the closing of his first epistle:

By Silvanus, a faithful brother as I regard him, I have written briefly to you, exhorting and declaring that this is the true grace of God; stand fast in it. She who is at Babylon, who is likewise chosen, sends you greetings; and so does my son Mark. Greet one another with the kiss of love. Peace to all of you that are in Christ (1 Peter 5:12–14).

The opponent reads this and triumphantly declares, “See! Here is proof that Peter was not in Rome at all, but in Babylon!” In fact, our friend here does the same:

“The church that is at BABYLON, elected together with you, saluteth you; and so doth Marcus my son.”

But not so fast. From the earliest times, readers of Peter’s letter have understood his reference to “Babylon” to be a figurative reference to Rome, which like Babylon, was capital of a great empire, a center of extravagance and excess, and an oppressor to the people of God. As St. Jerome recounted in his Lives of Illustrious Men (A.D. 391):

Mark the disciple and interpreter of Peter wrote a short gospel at the request of the brethren at Rome embodying what he had heard Peter tell. When Peter had heard this, he approved it and published it to the churches to be read by his authority as Clemens in the sixth book of his Hypotyposes [c. A.D. 200] and Papias, bishop of Hierapolis [c. A.D. 100], record. Peter also mentions this Mark in his first epistle, figuratively indicating Rome under the name of Babylon. “She who is in Babylon elect together with you saluteth you and so doth Mark my son.” (De viris illustribus 8)

Of course, the reference is much clearer in the Revelation, where “Babylon the Great” very plainly refers to Rome, and every first century reader would have understood that. But our friend also wishes to take issue with this:

The Catholic Church likes to say that Babylon is the code name for Rome. Yet when Bible believers point out to them Babylon is listed again in Rev. 17 – the whore of Rome – they quickly dismiss this by claiming that this is ancient Rome.

I’m not entirely sure I understand his objection here. Is he agreeing that “Babylon” is Rome, or rejecting it? Even opponents generally agree — in fact, insist, that “Babylon the Great” is Rome, and the Catholic Church has always accepted this. Turning to the Revelation:

And [the angel] carried me away in the Spirit into a wilderness, and I saw a woman sitting on a scarlet beast which was full of blasphemous names, and it had seven heads and ten horns. The woman was arrayed in purple and scarlet, and bedecked with gold and jewels and pearls, holding in her hand a golden cup full of abominations and the impurities of her fornication; and on her forehead was written a name of mystery: “Babylon the great, mother of harlots and of earth’s abominations.” And I saw the woman, drunk with the blood of the saints and the blood of the martyrs of Jesus. When I saw her I marveled greatly. (Revelation 17:3–6)

Our friend continues:

However, that won’t do! John the apostle who had travelled far with the Gospel, when shown this beast by the angel in Revelation 17:6, looked at it with “great admiration.” Why would he have admired it, if he had lived under Roman occupation ALL OF HIS LIFE?

I am confused by this. Apparently, he is arguing that the beast could not be Rome, because John, who lived under Roman oppression, would not have looked upon Rome “with great admiration”? This seems a strange objection. Even if one were under severe persecution unto death, I can tell you that the ancient city of Rome would have appeared most magnificent! But that is not what the Revelator is even saying here. Our friend, reading the King James Version, misunderstands. The text, even in the KJV, reads that John “wondered with great admiration”. To “wonder” is to look with awe, astonishment, surprise, at something astounding or miraculous — which seeing a woman arrayed in purple and scarlet, seated upon a seven-headed, ten-horned beast would certainly be.

In fact, the angel’s explanation of the scene all but confirms the beast’s identity as Rome:

But the angel said to me, “Why marvel? I will tell you the mystery of the woman, and of the beast with seven heads and ten horns that carries her. … This calls for a mind with wisdom: the seven heads are seven mountains on which the woman is seated; they are also seven kings, five of whom have fallen, one is, the other has not yet come, and when he comes he must remain only a little while. As for the beast that was and is not, it is an eighth but it belongs to the seven, and it goes to perdition. (Revelation 17:7–14)

The ancient city of Rome, it was famously known, spans seven hills, called in Latin montes, “mountains.” The description of a beast “seated on seven mountains” would have been an explicit reference to Rome to any first-century reader. The “seven kings” were Roman emperors who ruled in close succession during a period of unrest and persecution, and would also have been readily understood as a reference to Rome. For a deeper discussion of their identity, see Jimmy Akin’s excellent video series: [Part 1] [Part 2]

Further arguments in favor of “Babylon” being Rome are the presence of Mark by Peter’s side — who was known to have been in Rome with Paul at roughly the same time (cf. Colossians 4:10–11, Philemon 23–24 and see my other post for a lengthier discussion). Silas (Silvanus), too, a constant companion of Paul, would naturally have been in Rome.

Our friend continues:

So the reader is presented with three options:

- Peter died in Jerusalem?

- He died in Babylon?

- Or he went to Rome and died there? This of course being the most unlikely and difficult to prove, for Scripture is silent on this.

I don’t know why anyone would conclude from these Scriptures that Peter died in Jerusalem. Regarding the actual city of Babylon, it would have been a most unlikely destination for any evangelistic enterprise: the city, having been in decline for many years since the relocation of the capital to Seleucia, and then sacked by the Persians, lay in ruins, according to contemporary accounts (see my other post for a more detailed discussion).

Regarding Rome being “the most unlikely and difficult to prove,” and “Scripture [being] silent on this,” I will leave that for the reader to judge.

“Another man’s foundation”?

Another common objection against Peter’s having been in Rome is the fact that Paul does not mention him in his epistle to the Romans. But an argument from silence proves nothing. There is no necessity in believing that Peter remained in Rome constantly during his ministry there. It is apparent from Paul’s letter that Peter was not in Rome at that time; but nothing in his letter precludes Peter’s having been there. Indeed, there was evidently a thriving Christian community there, judging by Paul’s letter. Somebody had been ministering there.

Our friend, however, raises another possible objection:

I would also refer the reader to a verse that most Catholic apologists conveniently miss, when trying to propagate their false notion that Peter was in Rome with Paul:

“And so I have made it my aim to preach the gospel, NOT WHERE CHRIST WAS NAMED, lest I should build on ANOTHER MAN’S FOUNDATION” (Rom. 15:20.)

It is quite clear from the above Scripture that Paul would not and did not visit and lay a foundation to a new or existing church, if an apostle or evangelist had already been there.

But I would argue that our friend is misunderstanding the context of this quotation. The full passage reads:

In Christ Jesus, then, I have reason to be proud of my work for God. For I will not venture to speak of anything except what Christ has wrought through me to win obedience from the Gentiles, by word and deed, by power of signs and wonders, by the power of the Holy Spirit, so that from Jerusalem as far round as Illyricum I have fully preached the gospel of Christ, thus making it my ambition to preach the gospel, not where Christ has already been named, lest I build on another man’s foundation, but as it is written,’“They shall see who have never been told of him, and they shall understand who have never heard of him.”

It has been Paul’s ambition, up until this point, to bring the gospel to lands that had not yet heard the gospel of Christ. He has not wanted to build upon another man’s foundation, but to reach the lost who had not yet heard His name. But Paul continues:

This is the reason why I have so often been hindered from coming to you. But now, since I no longer have any room for work in these regions, and since I have longed for many years to come to you, I hope to see you in passing as I go to Spain, and to be sped on my journey there by you, once I have enjoyed your company for a little. At present, however, I am going to Jerusalem with aid for the saints (Romans 15:17–25)

Paul’s desire to minister to areas unreached by the gospel has hindered him from coming to Rome. But now that he no longer has work to do in those untouched regions, he may at last come to enjoy the Romans’ company. The implications of this passage are in fact quite the opposite of how our friend wants to take it. Paul strongly implies that Rome has been reached by the gospel and that another man has indeed laid a foundation there. He gives every indication that another Apostle had been ministering in Rome before him.

“You will stretch out your hands”

Our friend raises another argument from silence:

The Apostle John, who outlived all the apostles, never mentions “pope” Peter’s death, burial or even “succession.”

It seems a strange thing to expect. Does John inform us about the doings of any others of the Apostles or the goings-on in any other churches than his own? For that matter, does he even inform us about his own? John’s epistles, unlike Paul’s, are devoid of any personal greetings or references. His Gospel is concerned with the life and ministry of Christ, and contains few references to proceeding events.

But in fact, John’s Gospel does contain a definite reference to the martyrdom of Peter:

[Jesus said to Peter, ] “Truly, truly, I say to you, when you were young, you girded yourself and walked where you would; but when you are old, you will stretch out your hands, and another will gird you and carry you where you do not wish to go.” (This he said to show by what death he was to glorify God.) And after this he said to him, “Follow me.” (John 21:18–19)

And this is not even a hidden or veiled reference: John points at it: “This he said to show by what death [Peter] was to glorify God.” So these words were supposed to have demonstrated to the reader in what manner Peter was to die. And indeed they did: To a first-century reader, to “stretch out one’s hands” was an explicit description of crucifixion. And this was not merely a prophecy, since by the time John penned his Gospel, Peter and all the rest of the Apostles had been deceased for decades. John tells us that Peter was crucified. And crucifixion being the Roman method of execution, this is a certain statement that Peter died within a Roman jurisdiction (which, of all the places mentioned above, the ruined city of Babylon in Mesopotamia would not have been).

The Historical Argument

Where Peter ended his life is a matter of historical fact. As such, historical sources can provide us valuable evidence regarding it. Opponents often make the assertion that there is “no historical evidence” that Peter was ever in Rome, but such is simply not true.

From the very earliest writings of the Church, numerous writers attest to Peter’s ministry, episcopate, and martyrdom in Rome. What is more, this testimony is unanimous. Not a single early writer places Peter’s death in any other place but Rome.

I have discussed these historical sources in greater detail in another post (see Early Testimonies to St. Peter’s Ministry in Rome). But here are a number of the earliest, clearest, and most important testimonies.

Clement of Rome

Clement of Rome penned his Epistle to the Corinthians to encourage the Corinthian Church to resolve a succession dispute in her leadership. It has traditionally been dated to c. A.D. 95 or 96, but a strong case can be made to date the letter as early as c. A.D. 70, within a few years of Peter’s death (see Thomas J. Herron, Clement and the Early Church of Rome: On the Dating of Clement’s First Epistle to the Corinthians). In either case, it reflects the earliest testimony to Peter’s and Paul’s deaths in Rome.

At this point in the letter, Clement recounts how envy and jealousy have led to many evils for the people of God — for examples, the murder of Abel, the selling into slavery of Joseph by his brothers, the persecution of David by Saul. And then he turns to “the noble examples of our own generation”:

But, to cease from the examples of old time, let us come to those who contended in the days nearest to us; let us take the noble examples of our own generation. Through jealousy and envy the greatest and most righteous pillars of the Church were persecuted and contended unto death. Let us set before our eyes the good apostles: Peter, who because of unrighteous jealousy suffered not one or two but many trials, and having thus given his testimony (μαρτυρήσας [martyrēsas]) went to the glorious place which was his due. Through jealousy and strife Paul showed the way to the prize of endurance; seven times he was in bonds, he was exiled, he was stoned, he was a herald both in the East and in the West, he gained the noble fame of his faith, he taught righteousness to all the world, and when he had reached the limits of the West he gave his testimony (μαρτυρήσας [martyrēsas]) before the rulers, and thus passed from the world and was taken up into the Holy Place,―the greatest example of endurance. To these men with their holy lives was gathered a great multitude of the chosen, who were the victims of jealousy and offered among us (ἐν ἡμῖν [en hēmin]) the fairest example in their endurance under many indignities and tortures. (Epistle to the Corinthians 5–6)

Clement is very careful throughout the course of his letter to maintain the distinction between the first person and second person pronouns — we, the Greek ἡμεῖς [hēmeis], i.e. the Romans, and you, the Greek ὑμεῖς [humeis], i.e. the Corinthians. Clement has just paired Peter’s and Paul’s martyrdoms together, and declared that they both died among us, that is, among the Romans.

Ignatius of Antioch

Ignatius, bishop of Antioch, was arrested c. A.D. 107, and over the course of his journey to the capital Rome to face his trial and certain martyrdom, he penned a series of letters to Christian Churches along his way in Syria, Asia Minor, and ahead to Rome. In his Epistle to the Romans, his tone changes to one of praise and exultation at his coming victory in death with Christ. In one of the most poignant passages from all of ancient literature, he urges the Romans:

I am writing to all the Churches, and I give injunctions to all men, that I am dying willingly for God’s sake, if you do not hinder it. I beseech you, be not “an unseasonable kindness” to me. Suffer me to be eaten by the beasts, through whom I can attain to God. I am God’s wheat, and I am ground by the teeth of wild beasts that I may be found pure bread of Christ. Rather entice the wild beasts that they may become my tomb, and leave no trace of my body, that when I fall asleep I be not burdensome to any. Then shall I be truly a disciple of Jesus Christ, when the world shall not even see my body. Beseech Christ on my behalf, that I may be found a sacrifice through these instruments. I do not order you as did Peter and Paul; they were Apostles, I am a convict; they were free, I am even until now a slave. But if I suffer I shall be Jesus Christ’s freedman, and in him I shall rise free. Now I am learning in my bonds to give up all desires. (Epistle to the Romans IV, from Kirsopp Lake, The Apostolic Fathers, Loeb Classical Library [Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1912], 231)

Here again Ignatius places Peter and Paul as a pair, and implies that the Romans have had personal contact with them as Apostles, who enjoined them with authority.

Dionysius of Corinth

The Church historian Eusebius of Caesarea (see more below) preserves a document, no longer extant, by Dionysius, bishop of Corinth (c. A.D. 171), testifying that Peter and Paul both had ministered in Corinth prior to going to Rome, where they met their deaths at the same time (i.e. in the same persecution):

And that they both were martyred at the same time Dionysius, bishop of Corinth, affirms in this passage of his correspondence with the Romans: “By so great an admonition you bound together the foundations of the Romans and Corinthians by Peter and Paul, for both of them taught together in our Corinth and were our founders, and together also taught in Italy in the same place and were martyred at the same time.” And this may serve to confirm still further the facts narrated. (Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History II.25.8, trans. Kirsopp Lake, Loeb Classical Library [Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1926], 183)

Irenaeus of Lyon

Irenaeus, bishop of Lyon, writing c. A.D. 180, likewise, in giving an account of the penning of the Gospels (in the same passage cited above for the authorship of the Gospel of Matthew), testifies that Peter and Paul together “laid the foundations of the Church of Rome”:

For, after our Lord rose from the dead, [the Apostles] were invested with power from on high when the Holy Spirit came down [upon them], were filled from all [His gifts], and had perfect knowledge: they departed to the ends of the earth, preaching the glad tidings of the good things [sent] from God to us, and proclaiming the peace of heaven to men, who indeed do all equally and individually possess the Gospel of God. Matthew also issued a written Gospel among the Hebrews in their own dialect, while Peter and Paul were preaching at Rome, and laying the foundations of the Church. After their departure, Mark, the disciple and interpreter of Peter, did also hand down to us in writing what had been preached by Peter. (Against Heresies III.1.1)

Clement of Alexandria

Clement of Alexandria, writing between c. A.D. 190 and 200, likewise gave an account of Mark, the founder of the see of Alexandria: