Recently I’ve been writing about assumptions and presumptions that Protestants make in reading the early history of the Church: particularly the presumption that if the Church they observe in early documents does not resemble their Protestant one, then it must have apostatized from the true, apostolic faith of Christ that they read in Scripture. Scripture speaks with enough generality that they can project their Protestant interpretation upon it; but the image of the subapostolic Church, becoming clearer with even the earliest Church Fathers, allows no such reading.

This notion of an apostate Church is more than just my idle speculation: it forms the centerpiece of one of the most prevalent Protestant interpretive frameworks for understanding the history of the Church. The so-called “Great Apostasy” narrative is ubiquitous in Protestant literature, appearing in some form even in the writings of Luther and Calvin (who identified the papacy with the Antichrist), but is most pronounced in the thought of Christians of the nineteenth-century Restorationist movement, including the Churches of Christ and Seventh-Day Adventists. The Mormons and Jehovah’s Witnesses, sects which originated as part of the same movement, base their doctrines in similar claims.

The most troubling thing about this thesis, to me as a Catholic and especially as an historian, is that it is almost completely impervious to fact. Even when presented with the very earliest of the Church Fathers — say, the authors of the Didache (c. A.D. 70s), who suggest Baptism by effusion (pouring) as a valid alternative to immersion; Clement of Rome (c. A.D. 70s?), who argues for authority by apostolic succession; or Ignatius of Antioch (c. A.D. 107), who clearly states his belief in the Real Presence of Christ in the Eucharist, and unequivocally places local authority in the hands of a single, pastoral bishop — proponents of this “Great Apostasy” theory reject such writings, arguing that, since these doctrines do not fit with their own biblical interpretations, it demonstrates that the Church had already fallen away from “biblical truth,” even within the lifetimes and memories of the Apostles and within the era of New Testament authorship. When presented with documented fact, even from primary sources or eyewitness testimony, they maintain that the “apostate” Catholic Church altered documents and falsified historical evidence to support its own version of events. When proponents of a belief reject even the most basic laws of evidence and authority, in favor of claims based in nothing more than unfounded self-assertion, an irrational invincibility results that borders on delusion.

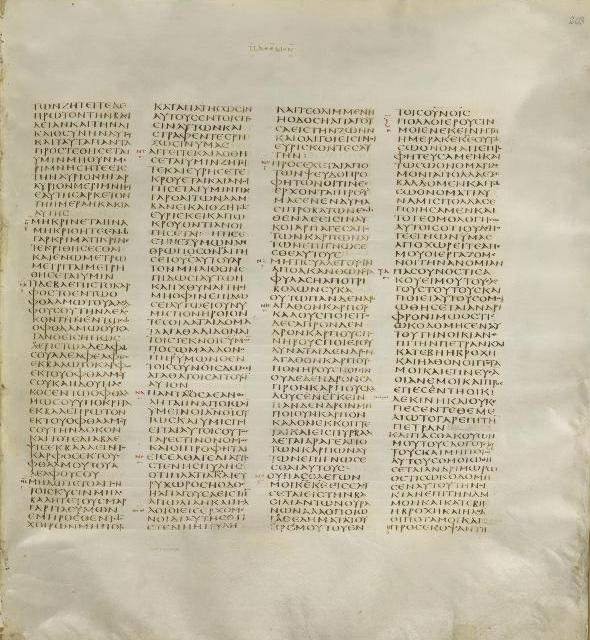

These claims do not stand up to logic. If the Church had “apostatized” from “biblical truth” so soon, and over the centuries conspired to falsify historical evidence to support its false doctrines — why did she not also alter the biblical texts to support such doctrines? Why not insert explicit teachings about hierarchical papal authority, Marian veneration, the use of images in worship? Proponents’ answer, of course, is that the Holy Spirit miraculously preserved the biblical texts from error, even as the Church corrupted every other document and erased from history the teachings of “true Christians” — but if this were true, why could not the Holy Spirit, whom the Lord promised would guide His people into all truth (John 16:13), have also preserved the Church? — the hearts and minds of His people, and the shepherds of His flock? These are very often the same opponents who argue that the Catholic Church corrupted the text of Scripture in such early biblical manuscripts as Codex Sinaiticus and Codex Vaticanus (they accepting arbitrarily the later, far more meddled-with Byzantine manuscripts) — thus allowing that the Church could corrupt the biblical text — and yet even in these “corrupt” manuscripts, apparently left unguarded by the Holy Spirit, there does not appear to have been any deliberate effort to falsify or deceive. These opponents have a substantial burden of proof to even allege such motives, given the observable nature of the textual variants.

Major claims of this “Great Apostasy” thesis include:

-

Catholic Christianity is a late invention (usually fourth century or later), the result of an amalgamation of Christian truth and elements of pagan philosophy and worship, an effort by the Roman government to adopt Christianity and make it more palatable to pagan Roman citizens. The compromise and “watering down” of the faith was readily accepted by Romans, at the expense of the truth of the gospel.

-

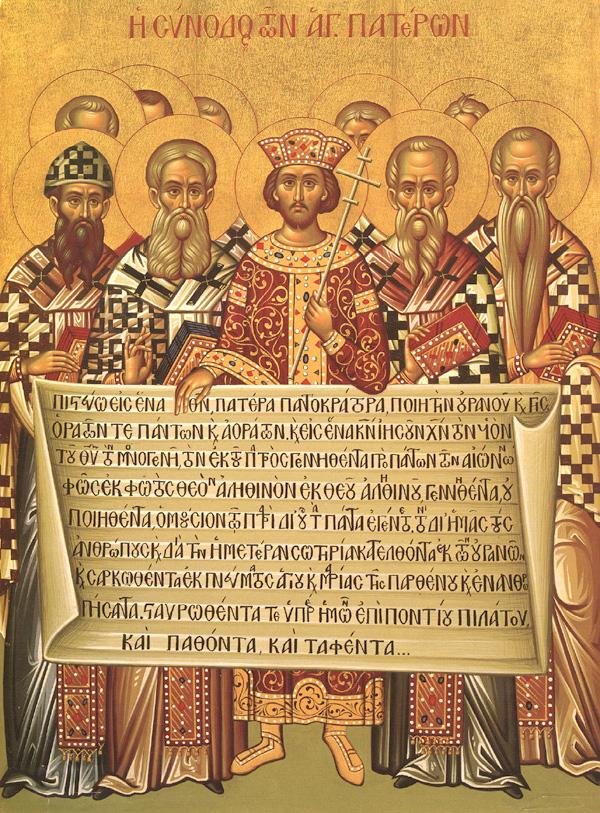

The Roman emperor Constantine was the essential culprit of this enterprise, an enthusiastic and devout pagan sun worshipper who embraced Christianity merely as a political ploy and never truly converted to the faith. He declared himself head of the Roman Church and exercised autocratic authority to alter the doctrine of Christianity and introduce pagan elements.

-

The worship of images — both icons and statues — was introduced as a substitute for pagan idolatry, to Romans who were accustomed to having statues and images to worship. The mere existence of such images was in direct contradiction to the Ten Commandments, and the Catholic Church accordingly removed the commandment concerning “graven images” to hoodwink the Christian people.

-

The Catholic Church moved Christian worship to Sunday from the Jewish Sabbath (Saturday) to unite it with pagan sun worship, of which Constantine was a devotee. True Christians kept only the Sabbath. The new pagan regime of the Church instituted persecution of Jewish Christians and purged all Jewish elements from the Christian Church.

-

The worship of the Virgin Mary was introduced as a substitute for pagan goddess worship, particularly for popular mother deities like Isis or Cybele. Proponents of this idea point to the prophet Jeremiah’s polemics against the “queen of heaven” (e.g. Jeremiah 7:18) as evidence of Catholic apostasy, or to pagan deities of whom perpetual virginity (e.g. Athena, Artemis), heavenly queenship (e.g. Hera, Juno), or virgin motherhood were claimed.

-

The Mass, the Catholic understanding of the Lord’s Supper, was a repackaged pagan ritual, an adaptation of Christ’s ordinance to animal sacrifice and consumption, with distinct and un-Christian connotations of cannibalism. The repetition of the Mass is in mirror of the need to repeat pagan sacrifices, and is a denial of the completeness of Christ’s work on the cross.

-

The highest indication of the Church’s apostasy is the office of the papacy, which united elements of the Roman emperorship and the pagan high priesthood, and presents itself as a “replacement” for Jesus on earth as head of the Church and “Vicar of Christ,” with quasi-divine elements such as supremacy and infallibility. The pope is identified with the Antichrist and the “son of perdition” of 2 Thessalonians 2:3.

-

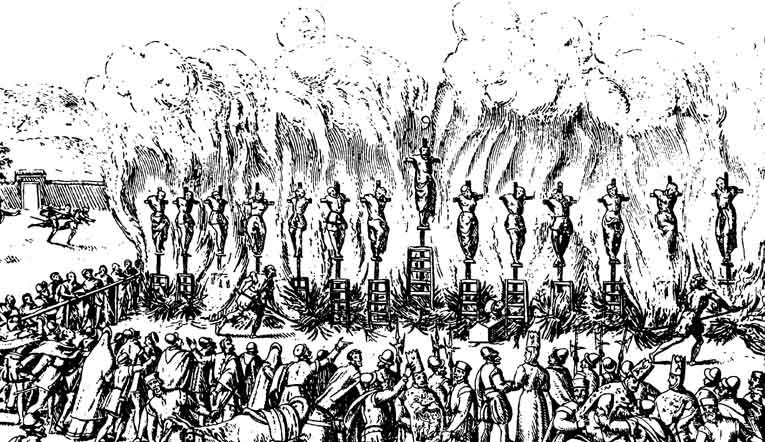

The Catholic Church committed mass murder in Europe, wiping out thousands, even millions of people (as many as 50 million) who voiced opposition to Catholic doctrine, through such devices as the Crusades and the Inquisition — ostensibly Protestants and proto-Protestants, as the Church sought to quell the inevitable rebellion of true Christians who would refute its falsehoods and rediscover the faith of Christ.

-

But there have always been “true” Christians existing as an underground, persecuted minority — sects outside the Catholic Church who secretly read the Bible and adhered to true biblical doctrine, all the while being sought, oppressed, and murdered by Roman operatives. These sects have been maligned by history as “heretics,” and the Catholic Church suppressed their true teachings and obliterated their writings, erasing any trace of their truth from history.

-

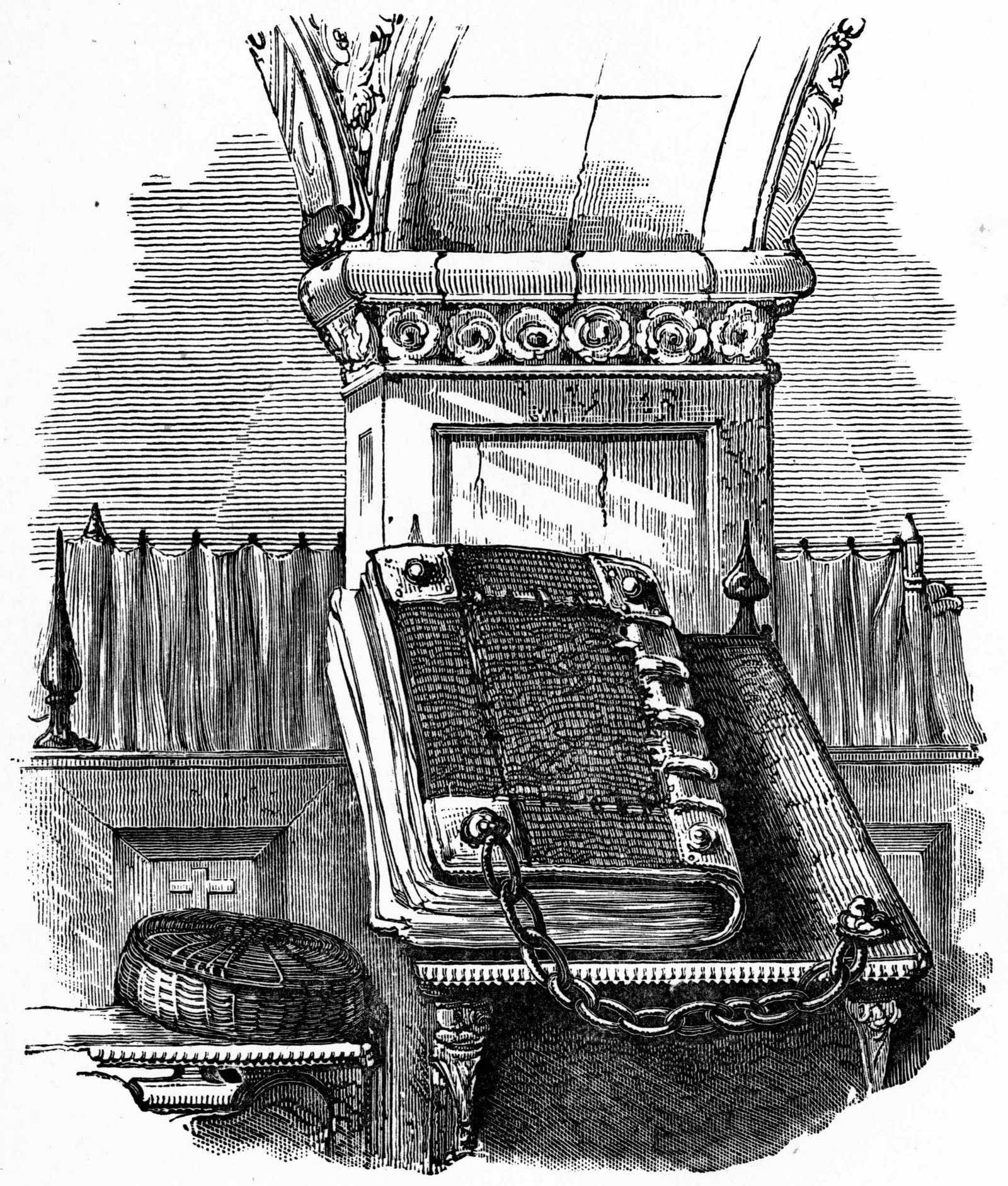

The Catholic Church prohibited the reading of the Bible by laypeople, and kept Scripture “locked up” in incomprehensible languages and away from the people for centuries. Christians were persecuted, arrested, even executed, for merely possessing copies of Scripture, let alone reading or attempting to translate it.

Many Protestants — even those who deny such a broad claim as that “the Catholic Church was completely apostate from the truth of Christ” — readily accept many of these suggestions or their implications. In future posts, I will examine each of these claims and indicate their logical fallacy and lack of historical foundation.

Excellent post – I look forward to the follow ups. As an aside to this topic, what do you make of arguments such as this one:

http://theophiletos.wordpress.com/2014/06/10/the-argument-from-dis-similarity/

where the author contends that because there was so much diversity in the early Church, that visible features of the Church, while important and useful, are not essential features?

It is a variation of the old ‘the true Church is the invisible Church – the sum total of all Christians’ argument, and I am seeing it more and more in Protestant circles – confronted with the baffling diversity of doctrine and practice amongst denominations, and rather than considering Catholicism or Orthodoxy as live options (either because of prejudice or because they do not see an exact identity between these today and the apostolic Church), many seem to be embracing a ‘God doesn’t really care that much about doctrine after all’ position.

I have found it hard to convince those who support this theory that not only is this not a good argument for Protestantism per se (as the early Church shows very little kinship with Protestant thought and practice), but also that just because there is diversity in the early Church and a sometimes frustratingly incomplete set of data in support of certain doctrines, this doesn’t mean the invisible theory is the only option. Have you come across this before at all?

Thanks! I’m looking forward to them, too.

As for the “argument from dissimilarity”: it’s specious — for the very same reasons that I think most “arguments from similarity,” in trying to link one’s church to the Apostolic Church, are ultimately inconclusive. Rather than asking what something is like or not like — highlighting the things that are similar or dissimilar — the more important question is what something is ontologically. Yes, it’s quite true that no church today is completely like the Apostolic or Subapostolic Church — as I’ve been arguing, some being more unlike than others. But what I’m arguing here is not that Protestants are wrong simply because their churches are unlike the Apostolic Church — but that they’re wrong because those unlikenesses call into question their basic beliefs about themselves, that they are a “restoration” of the Early Church. Both Catholic and Orthodox traditions have a legitimate claim to being like the Apostolic Church — and the author is right, one can’t readily pick one over the over, based only on similarities. But to conclude that, because of that inconclusiveness, neither could be the true Church, is specious and a cop-out.

I think most knowledgeable Protestants realize that they are dissimilar, but argue that they are a true and godly thing anyway. The problem that I’d like to point out is that, even if they are a true and godly thing, their whole reason for being in the first place was the proposition that the Catholic Church was not a true and godly thing — and that the beliefs that Protestant churches are true and godly things and that the Catholic Church is also a true and godly thing are self-contradictory. This resort to an “invisible Church” presumes that if there is more than one “true Church,” then all who are in communion with Christ must be true Churches. But whoever concluded that there was more than one “true Church”? Is this not begging the question? What did the Early Church consider itself to be? Did early Christians hold that their dissimilarities somehow separated them? No, they all universally held that despite their developing differences, they remained part of one and the same Body of Christ — the same Church. It was not until that unity was dissolved that anyone began thinking about any “invisible Church.”

Back to “dissimilarity”: The author makes some unsupportable assumptions, presuming that the leadership structure of the Church was diverse among various local churches. There’s no evidence of that at all. Scripture does equate bishops and presbyters, as do, apparently, both the Didache and Clement of Rome’s letter. But then, all of a sudden, Ignatius addresses all these diverse churches along his way and admonishes them to adhere to their one bishop, as if the monoepiscopacy were a fait accompli everywhere. There’s no indication of diversity at all there. By all appearances, everywhere at roughly the same time, between the A.D. 70s and the end of the Apostolic Era, all the churches everywhere spontaneously and uniformly decided to adopt a model of a single bishop over a college of presbyters. One might be inclined to suspect that perhaps these churches were communicating with one another, or perhaps even some authority had spoken on the matter.

He concludes that “early Christian worship practice varied” from, as far as I can tell, no evidence at all — from the fact that modern Christian worship varies? This conclusion does not seem to follow his argument at all. As he admits, we have only one or two glimpses of the liturgy of the Early Church — but I think here, the similarity of the basic liturgical structure that has existed everywhere and for all time, in both the East and the West, is overwhelming. The words and specifics of the liturgy have changed, but examining the earliest complete liturgical texts we have, the scholars I have read conclude not an origin in diverse practices, but a common, apostolic origin for all. (I recommend Adrian Fortescue on the History of the Mass — which focuses on the Mass, but the opening chapters on the origins of the Mass treat all early liturgy.)

As I said, the more important question to ask, I think, is what did the Early Church understand herself to be? What made them “Church”? From the very earliest times, as evidenced by Clement’s letter and especially Ignatius’s admonitions, it was communion with one’s bishop who held a valid succession from the Apostles that made one “in the Church”; anyone who strayed from the leadership appointed by the Apostles was not.

“See that you all follow the bishop, as Jesus Christ follows the Father, and the presbytery as if it were the Apostles. And reverence the deacons as the command of God. Let no one do any of the things appertaining to the Church without the bishop. Let that be considered a valid Eucharist which is celebrated by the bishop, or by one whom he appoints. Wherever the bishop appears let the congregation be present; just as wherever Jesus Christ is, there is the Catholic Church” (Ignatius to the Smyrnaeans 8, trans. Lake).

Both the Catholic and Orthodox Churches claim, to this day, to be in communion with their bishops, who hold valid successions from the Apostles. And the Catholic and Orthodox Churches both recognize each other’s legitimacy in that regard. So what makes one the “true” Church and the other schismatic? How can one come to that conclusion? The key element, the source of unity in the Church, is the papacy. Just as Jesus appointed Peter to “strengthen his brethren” and “feed His sheep,” the Petrine office is what must hold the Church together. St. Irenaeus, St. Cyprian, so many Early Fathers and Fathers throughout history, in both the East and the West, affirm it again and again. And the Orthodox departed from that unity. It leaves no question at all in my mind who has the legitimate claim, and it should not in anyone else’s who accepts these basic facts. “Similarity” or “dissimilarity” cannot mark the true Church; but the marks of the Church, what the Church has always understood herself to be, and most important, the papacy, can.

Thank you very much for your reply. A couple of points you have raised here I already put to the author of the post in the comments board, but they were not accepted because (it seems to me anyway) he is working with the concept of an essentially invisible Church as an a priori concept, and allowing it to determine how the rest of the data is seen. You’ve given them a lot more substance here, which is very helpful.

The points you’ve made here about the liturgy and the self-understanding of the Church are particularly helpful, as is the re-affirmation of the testimony to Petrine primacy. Concerning the latter, one hears so often from Protestants that there was barely any support for this in the East, that doubts start to creep in – so it is good to be reminded of the truth!

A couple more things that I come across (and did so in my comments exchange on the post in question) is that a.) contemporary antipathy towards the papacy amongst Orthodox is the same thing as official Orthodox denial of the special role of the papacy (not as Catholics would see it, but certainly an affirmation of primus inter pares status), and b.) that because many Catholics and Orthodox (in the West at least) take a cafeteria approach to Church teaching, this somehow validates the Protestant approach to Tradition. Both of these again seem to me to assume the idea that the Church is just the sum total of the people in it, and that there is no essential institutional dimension able to authoritatively pronounce on faith and morals. Frustrating positions to encounter nonetheless! 🙂

Brilliant!!!

As Cardinal John Henry Newman an Anglican convert to the Catholic Church said “to be deep into history is ceases to be protestant”… can’t wait to read the follow up posts.

Keep ’em comming.

Blessed John Henry Newman pray for us!

Thanks. If any phrase could sum up the reasons for my conversion, that would be it. 🙂

That is amazing. I have so much respect for people like you that in away read themselves into becoming Catholics, like Newman. As a cradle catholics we take all this things for granted and ignore how beautiful and elegant our faith is.

Dear Joseph. I have read a lot of church history.

At least 50 million heretics was tortured and killed by the RCC.

The harlot is surely drunken by the blood of God’s holy people.

I could have given you a very long list of martyrs, here are two as a start:

John Hus:

http://wp.me/p3tGFm-3W

Balthasar Hubmaier:

http://wp.me/p3tGFm-3N

Is the inquisition going to return in the future, when protestants will deny the number of the beast?

Hi, shek1na. I wonder what “church history” you have been reading? History is based in historical facts and sources. There is no historical evidence at all that the Catholic Church, at any one time or even over all times, “tortured and killed” fifty million people, or even fifty thousand, or anywhere near this number. This is only a bald, baseless, empty claim invented by anti-Catholic Protestants with no foundation at all in fact.

The only time in history at which there is any evidence of “torture” at the hands of the Catholic Church is the Spanish Inquisition — during which time torture was used to elicit confessions, after which accused heretics (not Protestants, but usually Jewish converts who had professed Christianity but secretly continued to practice Judaism) were absolved and released. No one was “tortured and killed.” At the very most two thousand people were executed for heresy — only those who did not repent. Some of these people may have been innocent. I do not defend the Spanish Inquisition as a good or just thing, but to put it in perspective, contemporaries called the Inquisition “the most humane court in Europe” — not the murderous, bloodthirsty engine of death anti-Catholic myth has created of it.

Yes, Catholics executed Protestants during the Reformation. Protestants also executed Catholics. There is enough bloodshed and guilt to go around for all Christianity. It is a travesty and an abomination against the love and unity our Lord prayed his Church would have.

I do not wish to argue with you, and I seriously doubt you are open to factual evidence anyway. But on the off chance that you are, I will be glad to talk to you. If what you claim is true, then you should be able to present actual, documented evidence supporting it. People claiming it on the Internet, or on TV, or in books, without documented sources supporting them is not factual evidence.

In case you might be interested, here is a summary of evidence which contradicts yours:

Historical revision of the Inquisition

This is the work of secular, academic historians, not Catholic partisans or apologists.

I pray that you will be open to reason. May the grace, and peace, and love of the Lord be with you.

Thank you for the honest answer.

I have been reading church history printed in norwegian, my native language.

The most important book is “Kristendommens verdenshistorie”, by Fridtjof Valton. (Word history of Christianity).

Fox’s Book of Martyrs would be a good place to start:

http://www.biblestudytools.com/history/foxs-book-of-martyrs/

I pray for you also. May the Lord bless you and keep you.

Hi again. I’m not familiar with the Norwegian historian, so I can’t speak to his merits — but does that book cite its sources? I would be interested in hearing what it has to say.

Foxe’s Book of Martyrs (otherwise known as the Actes and Monuments) is a highly contentious work, with wide allegations that Foxe exaggerated or simply made things up. Some of his accounts, especially of the persecutions around his own time, may be more factual; but it was self-consciously a work of Protestant propaganda. I can’t be relied upon as a factual account of the Catholic Church.

If you read only Protestant propaganda, you will receive only a very biased view of the Catholic Church. If you would like a more balanced view, you would do well to read some secular accounts (e.g. encyclopedia articles or secular academic histories) or even Catholic accounts. Most Catholic historians in modern times have been honest about the church’s history, acknowledging the injustices that happened in the past.

His peace be with you!

The history is written by the survivors. Not written by martyrs and the persecuted. That’s the main problem.

Do you believe in the Iron Virgin?

Another thing. Do the title Pontifex Maximus have something to do with Circus Maximus?

I will try to check out Valton’s sources. God bless.

Hey Joseph. First off, I want to thank you for what you do. I am Catholic convert-in-process and the stuff you write has enriched me. I have an unfortunate ability to articulate what I mean when I discuss my conversion with friends, so you’ve been a good resource.

I wonder if you have ever encountered some of Peter Liethart’s stuff? More than once I have had his “Too catholic to be Catholic” argument presented to me. I would be interested to know how you might respond? I am linking to his article here: http://www.leithart.com/2012/05/21/too-catholic-to-be-catholic/.

Blessings!

Thank you, brother. I’m very glad my writings have been helpful, and praise God for your conversion! That is my highest prayer, that I can help other pilgrims on their way across the Tiber.

Thanks for pointing out the Leithart piece. I’d heard it alluded to but never read it firsthand. I’ll try to give the argument a more thorough response sometime soon, but my first reaction is the same as it has been in this continuing series: His position is only possible because he presumes a priori that his sect is fully “catholic” in all the senses he means that, that it is just as much and just as legitimately the true Church of Christ as the Catholic and Orthodox claim, that his tradition suffers no lack and no impediment from its schism, and that it was right in its initial disputes and justifications of the Reformation. In short, he can only claim to be “catholic” because he is wholly and unquestioningly Protestant, and does not believe the teachings of the Catholic Church, and in fact believes she is wrong. Thus, his whole argument about being “too catholic” really reduces to simply that he is “too Protestant.” Such an argument is essentially meaningless to any Protestant who is questioning his Protestantism; what he means by “catholic” is the standard sense that Protestants mean of that word, and not what the Catholic Church means of it at all.

As to his questions: As a Protestant, I too presumed a priori that my Protestant, Evangelical heritage and upbringing were legitimately Christian and my churches legitimately members of Christ. But I also very quickly realized the fullness that I was lacking — and thus even with my understanding of my Protestant background, I was entirely in line with Catholic teaching on the matter. Until a Protestant realizes and acknowledges that he has a lack, he is riding safely in Leithart’s boat.

How can the Catholic church depart from the authority of scripture and think it is still legitimate? How can it persecute Christians for looking to the bible as their authority?

Hi, sorry I missed your comment. It’s been a busy couple months.

The Catholic Church hasn’t departed from the authority of Scripture. Scripture always has been, and is still, the highest authority for Catholics. (Cf. “Sacred Scripture” in the Catechism).

The Catholic Church doesn’t, and never has “persecute[d] Christians for looking to the Bible as their authority.” It is a common anti-Catholic myth that the Catholic Church persecuted or hunted down Christians merely for possessing Bibles or translating the Bible. Yes, Catholics persecuted Protestants. Protestants also persecuted Catholics. But the rationale for persecuting Protestants was never that they “looked to the Bible as their authority”: the Catholic Church also looks to the Bible as her authority.

The peace of the Lord be with you.

Thank you for this helpful post. You mention that you will address each of these myths in subsequent posts. Were there, in fact, subsequent posts addressing these myths?

Hi, thanks so much for the kind comment. There were a few posts in this series: Reading Church History as a Protestant