(This is a matter I’ve written about before, but not all in one place. And it’s come up in a conversation, so I thought I would put it all together here.)

St. Peter Penitent (c. 1600), by Guido Reni. (Wikat least viiPaintings.org)

Anti-Catholics often claim that there is no evidence in Scripture that the Apostle Peter died in Rome or even ever went there. After all, wasn’t Peter the Apostle to the Jews, and Paul the Apostle to the Gentiles? What would Peter have been doing in Rome? Nevermind that early first century Rome had a Jewish population of over 7,000, perhaps many more; or that Peter was the first to preach to Gentiles, just as Paul ministered to Jews everywhere he went. And as a matter of fact, there is strong biblical evidence to place Peter in Rome by the close of the events of the New Testament.

She who is at Babylon

First, and most clearly: Peter tells us himself. In the closing of St. Peter’s first epistle, he writes:

By Silvanus, a faithful brother as I regard him, I have written briefly to you, exhorting and declaring that this is the true grace of God; stand fast in it. She who is at Babylon, who is likewise chosen, sends you greetings; and so does my son Mark. Greet one another with the kiss of love. Peace to all of you that are in Christ (1 Peter 5:12–14)

She who is at Babylon, who is likewise chosen, sends you greetings. Who is Peter talking about? Who is she? And how can someone who is in Babylon be sending greetings through Peter? Does that mean Peter is in Babylon? Let’s take this apart.

First of all, the Greek here — as well as an astute reading of the English — gives us a strong hint who she is. “She who is in Babylon, who is likewise chosen” is ἡ ἐν Βαβυλῶνι συνεκλεκτὴ [hē en Babylōni syneklektē]. What does he mean, likewise chosen? Who else is chosen? For the answer, we return to the opening of the letter:

Peter, an apostle of Jesus Christ, to those chosen sojourning of the Diaspora in Pontus, Galatia, Cappadocia, Asia, and Bithynia, according to the foreknowledge of God the Father, by the sanctification of the Spirit, for obedience and sprinkling with the blood of Jesus Christ: Grace to you and peace, may it be multiplied. (1 Peter 1:1–2, my translation)

I gave my own translation, more literal than any published one (so literal as to sound a little awkward, probably), to preserve the order and emphasis of Peter’s words: Peter’s address is to those chosen. The Greek word here is ἐκλεκτόι [eklektoi] — and this mirrors the word from 5:13, συνεκλεκτόι [syneklektoi = syn + eklektoi], also chosen. This word, ἐκλεκτός [eklektos], from ἐκ + λέγω [ek + legō] — it most literally means to choose out. It is the root of our English words elect and eclectic.

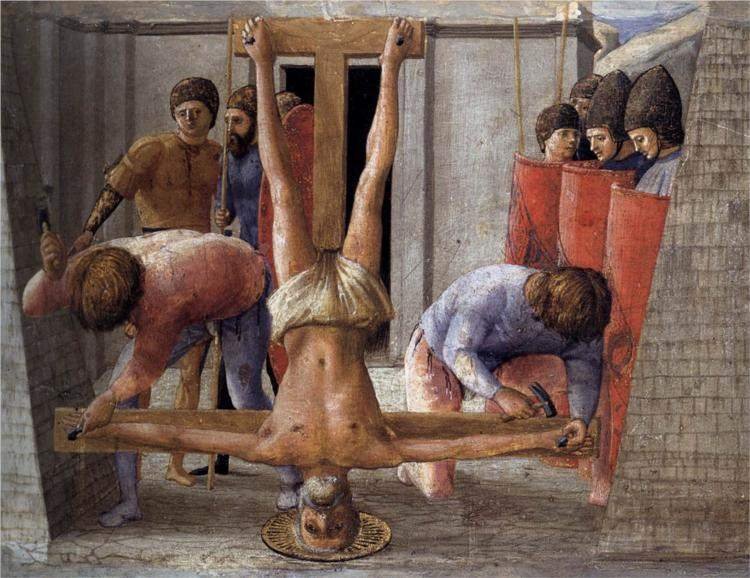

The Crucufixion of St. Peter (1426), by Masaccio (WikiPaintings).

We have here what is called an inclusio, a literary envelope by which the opening and closing of the letter bracket the contents. Peter wants to emphasize the fact of being chosen. The people to whom Peter is writing are those chosen by God, and she who is at Babylon is also chosen or elect. Elsewhere in the New Testament the “elect” refers to all Christians (cf. Luke 18:7, Romans 8:33, 2 Timothy 2:10). And in another place, we find a reference to an unnamed “elect lady”: John the Presbyter writes “to the elect lady and her children” (2 John 1) — and sends greetings from “the children of your elect sister” (2 John 13). Who are these elect ladies, if not the Church, sisters in different places?

But the elect lady at Babylon? If Peter is by her side, then he must be in Babylon, too, must he? Ah-ha! say the anti-Catholics. See! It says Peter was in Babylon, not Rome! But was he really in Babylon, the ancient city in Mesopotamia? Probably not. Alexander the Great conquered Babylonia, and the city of Babylon, in 333 B.C. (and died there). Following Alexander’s death, his vast conquests were divided between his leading generals. Seleucus took Babylonia, and founded the Seleucid Empire, with its capital at the newly-founded city of Seleucia. From that time on, the city of Babylon was in decline, until by the first century A.D. it was mere ruins. The Greek historian Diodorus Siculus (ca. 50 B.C.) attests:

But all these [temple treasures] were later carried off as spoil by the kings of the Persians, while as for the palaces and the other buildings, time has either entirely effaced them or left them in ruins; and in fact of Babylon itself but a small part is inhabited at this time, and most of the area within its walls is given over to agriculture. (The Library of History 2.9.9, ed. by C.H. Oldfather)

Peter would have no reason to be in the literal Babylon. Further, Peter writes as someone under the authority of the emperor (cf. 1 Peter 2:13–17), and as one experiencing the thick of Christian persecution (cf. 1 Peter 4:12, “the fiery trial”), when the first major Christian persecutions began in the city of Rome under Nero — and Mesopotamia was not yet under Roman rule in the first century. But if not the literal Babylon in Mesopotamia, where else might “Babylon” be?

The Beast seated on seven mountains

The Revelation of John refers to Babylon:

And I saw a woman sitting on a scarlet beast which was full of blasphemous names, and it had seven heads and ten horns. The woman was arrayed in purple and scarlet, and bedecked with gold and jewels and pearls, holding in her hand a golden cup full of abominations and the impurities of her fornication; and on her forehead was written a name of mystery: “Babylon the great, mother of harlots and of earth’s abominations.” And I saw the woman, drunk with the blood of the saints and the blood of the martyrs of Jesus. When I saw her I marveled greatly. But the angel said to me, “Why marvel? I will tell you the mystery of the woman, and of the beast with seven heads and ten horns that carries her. … This calls for a mind with wisdom: the seven heads are seven mountains on which the woman is seated; they are also seven kings, five of whom have fallen, one is, the other has not yet come, and when he comes he must remain only a little while (Revelation 17:3–5, 7, 9–10).

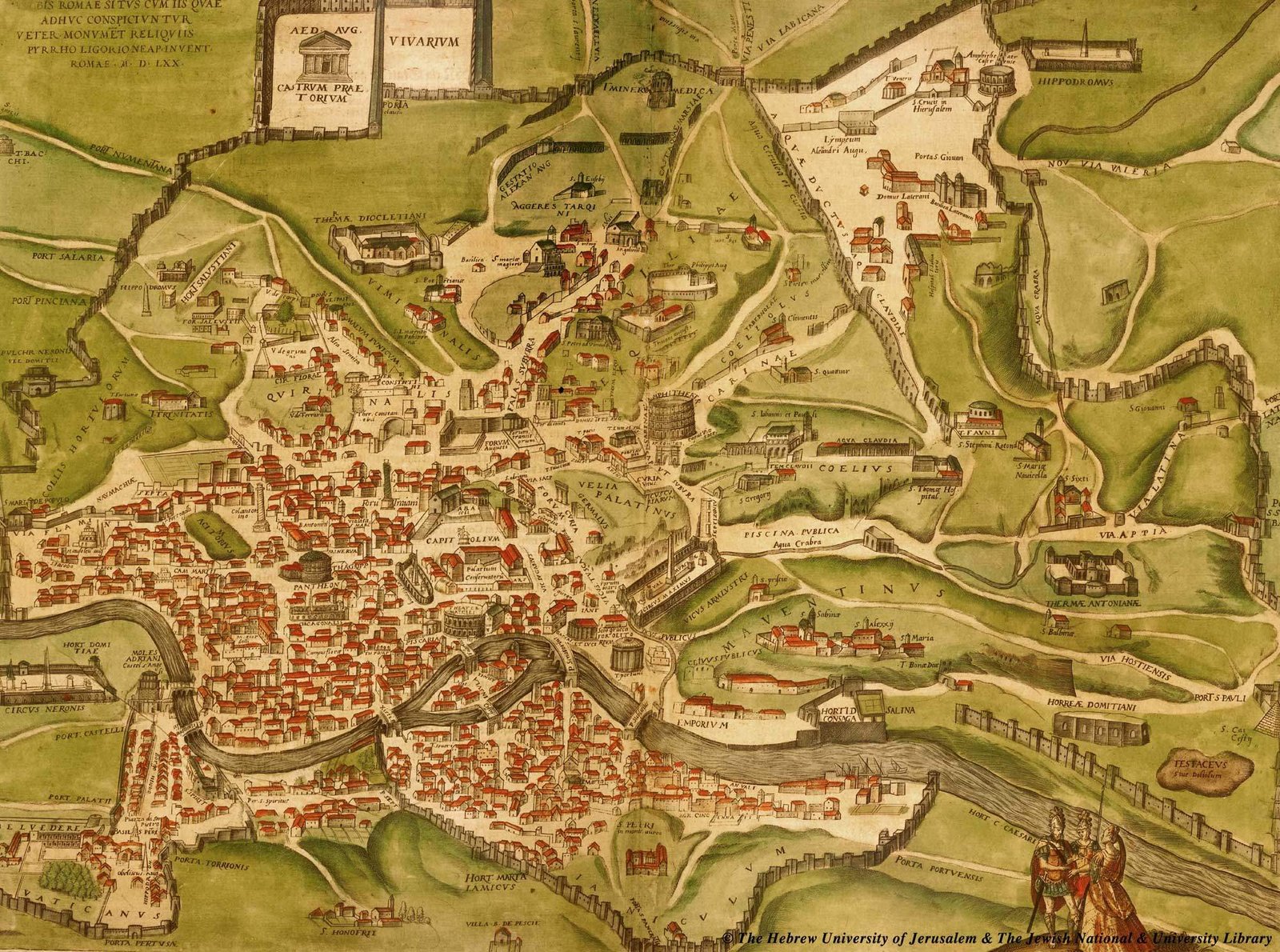

In this, John tells us quite clearly where, at least in his symbolism, Babylon is: A city arrayed in purple and scarlet, bedecked with gold and jewels, the mother of earth’s abominations, drunk the blood of the martyrs and saints of Jesus — and seated on seven mountains. One of the traditional marks of the city of Rome is that it was founded on Seven Hills (called in Latin montes, “mountains” — of which, for what it’s worth, the Vatican is not one; the Vatican was outside the walls of ancient Rome). And no other city in the time of the Apostles would have been such a visible image of decadence and extravagance, the capital of a great empire, the seat of fornication and abomination. As the Roman historian Tacitus remarked, it is in Rome “where all things horrible or shameful in the world collect and find a vogue” (referring, ironically, to Christianity). No other city in Peter’s day would have been more “drunk with the blood of martyrs and saints” — the author of the first great persecutions under the emperors Nero (which Tacitus wrote to describe).

But what of the “seven kings”? Can this also be understood to refer to Rome? Quite easily. It even supports an earlier dating of the Revelation than some have supposed, perhaps around the time of Peter’s martyrdom. First-century Rome was ruled by emperors, of whom the most aggressive enemy of Christians was Nero. This post is already too long, but I will allow the good Jimmy Akin to present for you compelling evidence identifying these seven kings and the Beast of Revelation: [Part 1] [Part 2]

It will suffice to say for now that there is very good reason for identifying the “Babylon” of Revelation with Rome — as even anti-Catholics do when they suppose that Catholic Church is the “whore.” If this was the attitude toward Rome in the first century, it would have been one with which Peter was well acquainted. Indeed, no other first-century city could have so aptly resembled the ancient Babylon: the capital of the civilized world, and of a great and mighty empire; the center of decadence and extravagance and idolatry. Peter has just informed us, without a doubt, that he is in Rome.

As does my son Mark

Saint Mark (1621), by Guido Reni WikiPaintings).

And so does my son Mark. In Peter’s closing, he also identifies for us two of his companions who are by his side in “Babylon.” Can this shed any light on Peter’s whereabouts?

Scripture mentions this Mark, the author of the Gospel of Mark, in a number of other places. When Peter was freed from the prison of Herod:

Peter came to himself, and said, “Now I am sure that the Lord has sent his angel and rescued me from the hand of Herod and from all that the Jewish people were expecting.” When he realized this, he went to the house of Mary, the mother of John whose other name was Mark, where many were gathered together and were praying (Acts 12:11–12).

So we see an association between Peter and Mark from the earliest days of the Church, attested to in Scripture.

Later in the same chapter, we find Mark accompanying Paul and Barnabas on Paul’s second missionary journey:

The word of God grew and multiplied. And Barnabas and Saul returned from Jerusalem when they had fulfilled their mission, bringing with them John whose other name was Mark (Acts 12:24–25).

But as they set out for their next journey, Paul and Barnabas had a disagreement over Mark:

And after some days Paul said to Barnabas, “Come, let us return and visit the brethren in every city where we proclaimed the word of the Lord, and see how they are.” And Barnabas wanted to take with them John called Mark. But Paul thought best not to take with them one who had withdrawn from them in Pamphylia, and had not gone with them to the work. And there arose a sharp contention, so that they separated from each other; Barnabas took Mark with him and sailed away to Cyprus, but Paul chose Silas and departed, being commended by the brethren to the grace of the Lord (Acts 15:36–40).

St. Peter Preaching in the Presence of St. Mark (c. 1433) (WikiPaintings).

Now this is important: Barnabas and Mark leave the scene, and Paul takes on a new companion, Silas — also known as Silvanus (cf. Acts 17:15, 18:5; 2 Corinthians 1:19; 1 Thessalonians 1:1; 2 Thessalonians 1:1).

Paul and Mark later reconciled. We next find Mark as a companion of Paul at the time of his writing the epistles to the Colossians and to Philemon:

Aristarchus my fellow prisoner greets you, and Mark the cousin of Barnabas (concerning whom you have received instructions—if he comes to you, receive him), and Jesus who is called Justus. These are the only men of the circumcision among my fellow workers for the kingdom of God, and they have been a comfort to me (Colossians 4:10–11)

Epaphras, my fellow prisoner in Christ Jesus, sends greetings to you, and so do Mark, Aristarchus, Demas, and Luke, my fellow workers. (Philemon 23–24)

We find in these letters that Paul is a prisoner. This is his first captivity — in Rome (cf. Acts 28:16).

Scholars date Paul’s first imprisonment in Rome, and the authorship of these letters, to the spring of A.D. 61 through the spring of A.D. 63 — which also happens to be the range of dates commonly ascribed to the authorship of the first epistle of Peter. So we have, direct from Paul in Scripture, testimony to the fact that Mark was in Rome. And if Mark was in Rome during that time, and was with Peter when he wrote his letter, then it is reasonable to conclude that Peter was also in Rome.

But what of Silvanus? Scripture makes no mention of him following Paul’s third missionary journey (Acts 18:5) — until we find him by Peter’s side in 1 Peter. But as Silvanus was a constant companion of Paul, it would be reasonable to assume that he at least visited Paul in Rome, if not moved the base of his apostolic operations there. The presence of Silvanus by Peter’s side, too, supports the conclusion that Peter was in Rome.

You will stretch our your hands

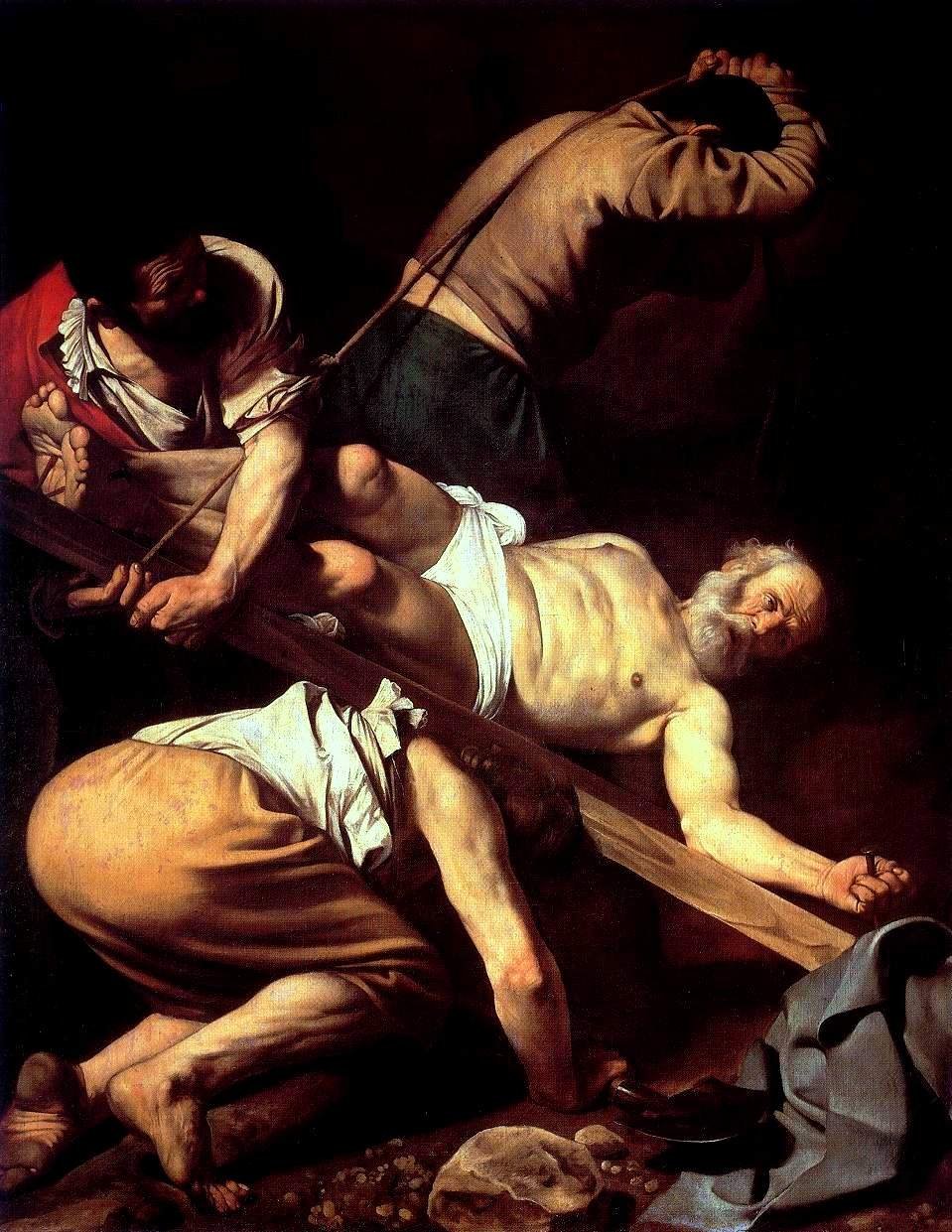

The Crucifixion of St. Peter (1600), by Caravaggio (Wikipedia).

We have one parting testimony to the end of Peter’s life — in the Gospel of John, widely held to have been one of the last-written books of the New Testament — certainly after the death of Peter:

Jesus said to him, “Feed my sheep. Truly, truly, I say to you, when you were young, you girded yourself and walked where you would; but when you are old, you will stretch out your hands, and another will gird you and carry you where you do not wish to go.” (This he said to show by what death he was to glorify God.) And after this he said to him, “Follow me.” (John 21:18–19)

You will stretch out your hands. In the ancient world — particularly in the Christian tradition — “to stretch out one’s hands” was an almost explicit reference to crucifixion. Indeed, to John the author, this language is meant to be clear to the reader: “This he said to show by what death [Peter] was the glorify God.” Certainly by the time of the writing of John’s Gospel, Peter’s martyrdom had already occurred — so if this were not a true description of Peter’s death (the details of which his readers would have known well), he would not have included it. Further, for Peter’s death to have been by crucifixion, he would have to have been living under Roman rule, since crucifixion was the Roman method of execution: this would not have been the case had he been living in Mesopotamia.

Indeed, the whole tradition of the Church affirms that this was the manner of Peter’s death:

Come now, you who would indulge a better curiosity, if you would apply it to the business of your salvation, run over the Apostolic churches, in which the very thrones of the Apostles are still pre-eminent in their places, in which their own authentic writings are read, uttering the voice and representing the face of each of them severally. . . . Since, moreover, you are close upon Italy, you have Rome, from which there comes even into our own hands the very authority [of Apostles themselves]. How happy is its church, on which Apostles poured forth all their doctrine along with their blood! Where Peter endures a passion like his Lord’s! Where Paul wins his crown in a death like John [the Baptist]’s [and] where the Apostle John was first plunged, unhurt, into boiling oil, and thence remitted to his island-exile! (Tertullian, Prescription against Heretics 36, ca. A.D. 180-200)

Thus publicly announcing himself as the first among God’s chief enemies, [Nero] was led on to the slaughter of the apostles. It is, therefore, recorded that Paul was beheaded in Rome itself, and that Peter likewise was crucified under Nero. This account of Peter and Paul is substantiated by the fact that their names are preserved in the cemeteries of that place even to the present day. (Eusebius of Caesarea, Church History II.25.5, ca. A.D. 290)

So we see that Scripture is plain in testifying to the ministry and death of Peter in Rome. Even those of a sola scriptura mindset should be satisfied. There is no sense in denying that Peter lived and died in Rome — to which the unanimous voice of the Church Fathers and other early writers of the Church testifies, dating to before the close of the first century, and which findings of archaeology confirm. If anyone would deny the truth of the Catholic Church, they must do so on other grounds than the historical.

I never thought any of this was important enough to fight over. You’ll remember my surprise when you first wrote on this subject, as I have never heard anyone try to argue the point strongly. While tradition is that Peter preached and died in Rome, it doesn’t affect my tradition or theology one bit if neither is actually true. The Roman Catholic Church is the only one with anything to lose if Peter did not found the Church in Rome, so I don’t understand why some Protestants are so vocal about it.

As my friend Laura pointed out, it’s as if they know it is true and are in vehement denial. It’s the strangest thing — because it doesn’t matter. Why would the Church of Rome, from the earliest times, “invent” the idea that the Apostle Peter ministered there? As if anybody in the first century ever conceived the notion of papal supremacy as we know it today or of the necessity of ever asserting such a claim. It’s like the American “birthers,” who suppose President Obama’s parents had the foresight to publish a notice of their son’s birth in the Honolulu newspaper, despite his being born in Kenya, somehow knowing he would need to run for president of the United States someday. It’s not even Roman sources that attest to Peter’s presence in Rome, for the most part. Clement of Alexandria, Irenaeus of Lyon, Tertullian of Carthage — and that’s just getting started.

Mr. Richardson, it must be noted that newspaper notices in Honolulu of births do not necessarily report that a child has been born there. Such notices at times only report that a birth has been recorded in the city or county records. Until a forensic examination of the actual birth certificate is made, demonstrating that it is printed on the same quality of paper as is found in records immediately before and after the Obama record, thee is reason to be doubtful. Remember, no actual records have been released for examination, and we have only the statement of the Democrat governor of Hawaii that the president’s birth record is in the possession of the proper authorities. This hardly serves as proof of anything. There being no effort on the part of the president to demonstrate “proof positive,” in fact a refusal to do so, we have further reason to doubt claims of authenticity.

My blog has nothing at all to do with President Obama. Do you also believe that St. Peter was never in Rome? That is the topic at hand.

Mr. Richardson, I am very late in responding to your reply to me on 01 December a year ago. If your blog has nothing to do with Obama, why then did you introduce him regarding birth announcements in your reply to Ken Ramos on 12 November?

All that aside, Mr. Richardson, I much appreciate your article. Godspeed.

Hi Joseph,

Do you have any references of credible Protestants that make the arguments that you describe here? Even though I am a Protestant, I have never heard any Protestants argue that Peter never went to Rome. So, I genuinely would like to see the arguments of Protestants that take this position.

Thanks,

Dale

Dale,

Thanks for the comment. I think “credible” is the key word. 🙂 The people I was talking to who prompted this post were not what I would call “credible,” breathing allegations along those of Jack Chick. Some people are so anti-Catholic that they will believe absolutely anything that contradicts Rome (e.g. that anything Catholic is a plot from Satan, and the Vatican is responsible for every evil from socialism to atheism to Islam).

But those people aside, there have been some more credible Protestants who have made these arguments. I read that Calvin followed this interpretation, that “Babylon” referred to the literal Babylon and not Rome, which wouldn’t surprise me, but I didn’t find that in a quick search through the Institutes. I don’t have many Protestant resources in my Logos collection (I have a Verbum package), but I did find this reference which is informative:

Babylon. Some understand in a figurative sense, as meaning Rome; others, literally, of Babylon on the Euphrates. In favor of the former view are the drift of ancient opinion and the Roman Catholic interpreters, with Luther and several noted modern expositors, as Ewald and Hoffmann. This, too, is the view of Canon Cook in the “Speaker’s Commentary.” In favor of the literal interpretation are the weighty names of Alford, Huther, Calvin, Neander, Weiss, and Reuss. Professor Salmond, in his admirable commentary on this epistle, has so forcibly summed up the testimony that we cannot do better than to give his comment entire: “In favor of this allegorical interpretation it is urged that there are other occurrences of Babylon in the New Testament as a mystical name for Rome (Apoc. 14:8; 18:2, 10); that it is in the highest degree unlikely that Peter should have made the Assyrian Babylon his residence or missionary centre, especially in view of a statement by Josephus indicating that the Emperor Claudius had expelled the Jews from that city and neighborhood; and that tradition connects Peter with Rome, but not with Babylon. The fact, however, that the word is mystically used in a mystical book like the Apocalypse — a book, too, which is steeped in the spirit and terminology of the Old Testament — is no argument for the mystical use of the word in writings of a different type. The allegorical interpretation becomes still less likely when it is observed that other geographical designations in this epistle (ch. 1:1) have undoubtedly the literal meaning. The tradition itself, too, is uncertain. The statement in Josephus does not bear all that it is made to bear. There is no reason to suppose that, at the time when this epistle was written, the city of Rome was currently known among Christians as Babylon. On the contrary, wherever it is mentioned in the New Testament, with the single exception of the Apocalypse (and even there it is distinguished as ‘Babylon, the great’), it gets its usual name, Rome. So far, too, from the Assyrian Babylon being practically in a deserted state at this date, there is very good ground for believing that the Jewish population (not to speak of the heathen) of the city and vicinity was very considerable. For these and other reasons a succession of distinguished interpreters and historians, from Erasmus and Calvin, on to Neander, Weiss, Reuss, Huther, etc., have rightly held by the literal sense.”

(Marvin Richardson Vincent, Word Studies in the New Testament, vol. 1 [New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1887], 673–674.)

My response to that: Calling the city “Babylon” doesn’t evince that Peter is being “mystical,” only that he is being cautious and probably ironic.

His peace be with you!

PETER WAS NEVER IN ROME.

1) Paul said: “Only Luke is with me” (II Tim. 4:11).

2) “At my first answer no man stood with me, but all men [in Rome] forsook me: I pray God that it may not be laid to their charge.”

3) At the end of Paul’s Epistle to the Romans he greets no fewer than 28 different individuals, but never mentions Peter once! See Romans 16

Hi, Dee. Thanks for the comment. Peter was never in Rome? Well, I have a wealth of evidence, historical and archaeological, in additional to the biblical here that you have not addressed — that says he was. What is more, the historical evidence is unanimous: there is no record, no statement by anyone at any time, that would support the belief that Peter served out his ministry and lived out his days in anywhere but Rome. Concerning Scripture, I have already addressed the concerns you raise here. Briefly:

1. The statement that “only Luke is with me” implies that only Luke was by Paul’s side, in prison. There were certainly other Christians in Rome, in fact a thriving community — or else there would have been no church there to persecute, as history records the Emperor Nero did in about A.D. 67, the occasion of both Peter’s and Paul’s deaths.

2. Certainly Paul does not include these Christians of Rome in the statement that “all men forsook me”: he is referring to the secular and pagan friends he had made who abandoned his cause and did not support him in the imperial court.

3. This only indicates that Peter was not in Rome at that time. Paul’s statements elsewhere in Romans about “building on another man’s foundation” (Romans 15:20) indicate that another leader, some other Apostle, had already been in Rome laying the church’s foundations.

Certainly your references never state that Peter was not in Rome; while in mine above, he himself states that he was. I am more inclined to believe his word over yours, as well as the unanimous testimony of history.

The peace of the Lord be with you!

Joseph,

Thanks for the reply. I agree that there are some Protestants who believe and repeat anything that would seem to contradict Roman Catholicism. Unfortunately, I also see the opposite problem of Roman Catholics fighting supposed Protestant claims that no credible Protestants hold and are therefore simply strawmen that are easy to burn down.

Regards,

Dale

Dale,

Yes, both sides are guilty of burning straw men. Really it’s a fallacy that’s easy for anybody on any issue to fall into. Thanks for keeping me honest. If you suspect me of doing that anywhere else, please call me on it. I do hope, having been a Protestant most of my life, that I understand Protestant positions. Although admittedly I never had very much theoloical depth as a Protestant.

Best regards,

Joseph

Was it Peter who came up with the doctrine of self-flaggelation or was it another pious Infallible guy who did it?

flagellation*

I rather doubt Peter thought of that. Ascetic practices had been a part of Judaism for thousands of years.

And yet I cannot find anything similar in Judaism. I can only find such self-mortification in Buddhism.

John the Baptist, hello? Do you think he wore camel’s hair and ate locusts and honey because he enjoyed it?

My contention is that John the Baptist did not whip himself, or did he? His asceticism was more in line with Nazaritism then that of JPII’s.

… How do you know he didn’t whip himself? Asceticism — the principle of it — has been a part of Christian tradition since before there was Christian tradition. The idea that “denying oneself and taking up one’s cross” was a path to righteousness was taught by Jesus Himself. And there’s one to top whipping oneself for you — let’s be “crucified with Christ.” Why do you object to the idea? If I thought whipping myself would bring me closer to God, I might do it, too. Such mortification is a private practice, done to reject this mortal flesh of ours — not to try to win God’s favor or any other such. And if that helps someone draw closer to God, what’s the problem with it?

Pingback: On the so-called “Jerusalem Tomb of St. Peter” | The Lonely Pilgrim

“Babylon” probably refers to Jerusalem (compare Revelation 11:8, which states that “the great city” is where the Lord was crucified, to Revelation 17:18, which states that Babylon the great is “the great city”)

Hi. Thanks for the comment. That’s an interesting theory, but why would you think there could only be one “great city” mentioned in Scripture? The Revelator calls the “great city” of Revelation 11 “Sodom and Gomorrah,” not “Babylon.” The description that the harlot of Revelation 17 is “the great city which has dominion over the kings of the earth” (Revelation 17:18) seems far more applicable to Rome than to Jerusalem. Curiously enough, it seems Jerusalem is also claimed to have been built on “seven hills,” though I can find no immediate evidence that this description was contemporary with the New Testament or that it is anything more than a post-hoc exegetical attempt to apply the “harlot” passage to some city other than Rome. Peace be with you!