Penitent Magdalene (c. 1597), by Caravaggio (WikiPaintings.org.

Part 2 of a series on Indulgences. Part 1.

So last time, I showed you the basic idea of indulgences: First, that sin has temporal consequences, apart from the guilt which Jesus forgives by His grace — the misery that our sin causes for us and others, called the temporal punishment, which we still must suffer even after our sins are forgiven (cf. Psalm 51). By the power of “binding and loosing” given to the Apostles (Matthew 18:18, John 20:22–23) the priests of the Church have the authority to impose penance on us — not a punishment, but a remedy designed to help us work through through that temporal punishment, to aid in the healing of our souls and our growth in grace. And because the Church imposed the penance, the Church has the power to remit it (cf. 2 Corinthians 2:6–11). And this is an indulgence at its most basic definition: the remission of a temporal penance caused by a sin whose guilt has already been forgiven.

Protestant critics suggest that Indulgences are a “medieval” doctrine, but in fact, the roots of the doctrine go back to the very dawn of the Church. And the doctrine, rather than being a late development, was formed in the crucible of the suffering and persecuted Church of the first centuries. We know that the sorrow of sin brings repentance, and repentance leads to salvation (2 Corinthians 7:10) — and the sufferings of a certain group of sinners came to be borne by the whole Church (cf. 1 Corinthians 12:24–26) — especially by those believers who gave their all, their very lives.

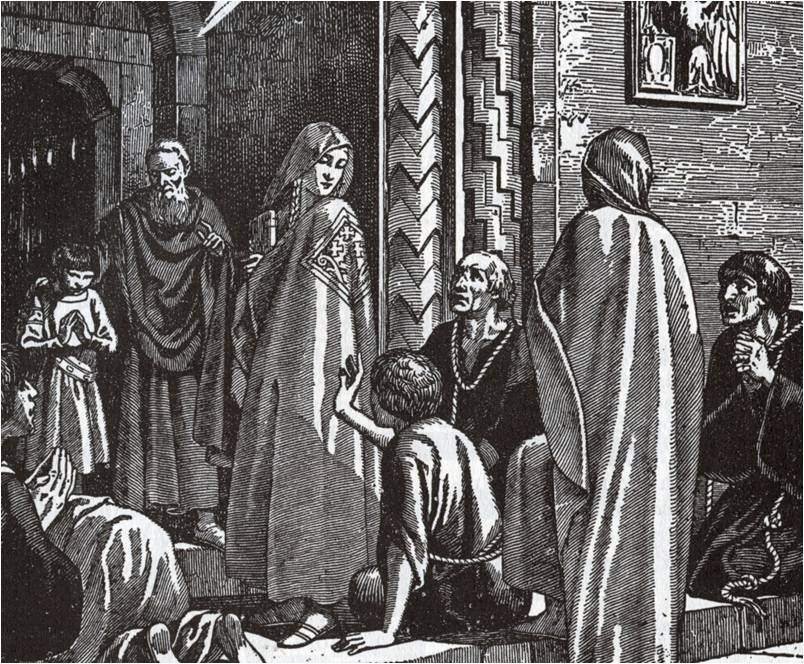

In the earliest centuries of the Church, the Church imposed especially harsh canonical penances for grave sins — not your common lusting with the eyes, arguing with a brother, or drinking intemperately, but major, public offenses against the moral law and against the community, like murder, adultery — or especially apostasy, which was increasingly a problem in the age of persecution. Many believers would renounce Christ when faced with arrest or bodily harm, only to repent later: these were the lapsi, those having lapsed. So the Church instituted an order of public penitents: believers who, even though the guilt of their sins had been forgiven, still had a penance to pay. These people would put on sackcloth and ashes and stand outside the church begging for the prayers of the faithful, often for a matter of years, before their debt to the community had been paid and they were allowed to return to the full communion of the Church.

(And if you think that is harsh, this is actually the compromise position. There was a schism in the Church for a time over the fate of the lapsi, with many believers following Novatian, who argued that the lapsi couldn’t be restored to the communion of the Church at all.)

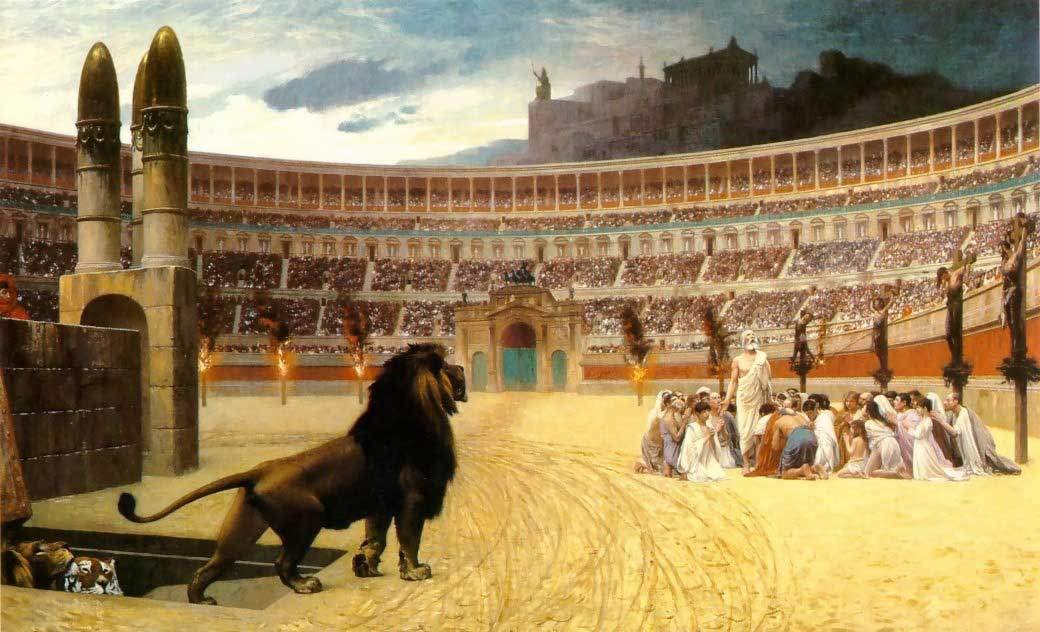

The Christian Martyrs’ Last Prayer (1883), by Jean-Léon Gérôme, my favorite Orientalist painter. It truly captures the drama and the agony of the first Christian persecutions, and yet the peace before God.

And from the Church’s crisis, these many lapsi longing desperately to return to the Lord’s communion, and the flowing blood of the many confessors and martyrs, a curious thing arose: The lapsi began visiting the condemned witnesses in prison before their impending martyrdoms, and obtaining from them letters or certificates pleading on their behalf — called the desideria or libelli of the martyrs — promising to offer up their sufferings on their behalf, and to intercede for them before God for their restoration when they reached heaven. And such assurance gave great comfort and grace to the fallen — and brought the bishops of the Church to credit such intercession to the cases of the lapsed.

We learn from the letter of the Churches of Vienna and Lugdunum (Lyons), dated ca. A.D. 177, possibly written by St. Irenaeus himself:

“[The witnesses] did not boast over the fallen, but helped them in their need with those things in which they themselves abounded, having the compassion of a mother, and shedding many tears on their account before the Father. They asked for life, and He gave it to them, and they shared it with their neighbors. Victorious over everything, they departed to God. Having always loved peace, and having commended peace to us, they went in peace to God, leaving no sorrow to their mother, nor division or strife to the brethren, but joy and peace and concord and love.” (quoted in Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History V.5.6–7)

St. Cyprian, bishop of Carthage, was at the very center of this crisis in the Church. His letters record an ongoing exchange about this matter: to what degree to reckon the intercession of the martyrs to the accounts of the lapsi, and if, and when, to restore them to communion. Regarding lapsi who were at risk of death, and had one last chance for Communion before their departure, and had received the testament of a martyr:

“They who have received a certificate from the martyrs, and can be assisted by their help with the Lord in respect of their sins, if they begin to be oppressed with any sickness or risk; when they have made confession, and have received the imposition of hands on them by you in acknowledgment of their penitence, should be remitted to the Lord with the peace promised to them by the martyrs.” (Cyprian, Epistle XIII [ANF ed.; XIX in Oxford ed.], A.D. 250)

Regarding the efficacy of such heavenly help, Cyprian wrote:

“[God] can show mercy; He can turn back His judgment. He can mercifully pardon the repenting, the labouring, the beseeching sinner. He can regard as effectual whatever either martyrs have besought or priests have done on behalf of such as these.” (Cyprian, De lapsis [On the lapsed] 36, A.D. 251)

We recognize these certificates or libelli as the first written indulgences. The intercession of the martyrs — now saints in heaven — brought remission to the punishments of the lapsi; and these documents were the proof of their aid. And herein we see the truth of what Indulgences are really all about: the communion of saints — our common life as the Body of Christ.

Next time: I’ll delve deeper into the theology of Indulgences — one of the most beautiful and powerful things I’ve encountered. Many folks argue that Indulgences are an “archaic” practice that should be dismissed; but I think rather they need to be taught more and better understood.

Thanks, Joseph. Nice scholarship. I hope your grad degree is in some area of theology? Theology departments in Catholic universities could sure use a faithful Catholic scholar like yourself!

Thanks. 🙂 My degree is in history, an area of history nowhere near the Church. But the Church has captured my heart now. At least the degree has taught me historical skills. For now, I am pretty burned out on academia, but I’m open to the idea of returning. I’ll go wherever God should lead.

Hey Joseph,

It seems that there is more to the libelli story.

Cyprian, it seems, espoused a scheme whereby penance was to be administered by the clergy. With the advent of the Decian persecution, the sheer number of apostasies precluded the clergy from being able to administer penance. So, apparently at a time when Cyprian was away, his clergy began the practice of disseminating these “certificates of peace” without his knowledge. W.H.C. Frend notes that this practice was “recognized as an abuse” and that “Cyprian had no serious difficulty in reasserting the bishop’s…control over penitential discipline.”

So, even if these libelli can in some magical way be equated with indulgences, Cyprian viewed them as an abuse and sought to have them stopped.

Interesting stuff….

That interpretation doesn’t fit the context of Cyprian’s letters. Cyprian is quite clear that the lapsi were receiving certificates “from the martyrs.” In these letters he is writing to his clergy, instructing them what to do about it, not admonishing them for anything the clergy were doing. This letter sounds like it may be the origin of the interpretation you propose (Epistle XIV in the ANF edition):

Moreover, when I found that those who had polluted their hands and mouths with sacrilegious contact [certain of the lapsi], or had no less infected their consciences with wicked certificates, were everywhere soliciting the martyrs, and were also corrupting the confessors with importunate and excessive entreaties, so that, without any discrimination or examination of the individuals themselves, thousands of certificates were daily given, contrary to the law of the Gospel, I wrote letters in which I recalled by my advice, as much as possible, the martyrs and confessors to the Lord’s commands.

The problem here seems to be that some of the lapsi are being abusive in their demands from the martyrs for these certificates, and some of the martyrs were turning out “thousands” of these certificates without even bothering to examine whether the sinners were truly penitent (this is what is contrary to the Gospel, not the certificates themselves). So he writes to restrain the martyrs and confessors from this practice.

Later in the same letter:

But afterwards, when some of the lapsed, whether of their own accord, or by the suggestion of any other, broke forth with a daring demand, as though they would endeavour by a violent effort to extort the peace that had been promised to them by the martyrs and confessors; concerning this also I wrote twice to the clergy, and commanded it to be read to them; that for the mitigation of their violence in any manner for the meantime, if any who had received a certificate from the martyrs were departing from this life, having made confession, and received the imposition of hands on them for repentance, they should be remitted to the Lord with the peace promised them by the martyrs.

So yes, some of the lapsi were being abusive. This also makes quite clear that it is the martyrs and confessors offering these certificates of peace, and that, especially to appease the violence, the priest should remit the penance of the lapsi who, having received a certificate from the martyrs, were truly repentant.

There’s no evidence at all, however, that Cyprian saw the practice itself, done piously, as an abuse. In Letter XXVI:

But some who are of the lapsed have lately written to me, and are humble and meek and trembling and fearing God, and who have always laboured in the Church gloriously and liberally, and who have never made a boast of their labour to the Lord, knowing that He has said, “When ye shall have done all these things, say, We are unprofitable servants: we have done that which was our duty to do.” Thinking of which things, and even though they had received certificates from the martyrs that their satisfaction might be admitted by the Lord, these persons beseeching have written to me that they acknowledge their sin, and are truly repentant, and do not hurry rashly or importunately to secure peace; but that they are waiting for my presence, saying that even peace itself, if they should receive it when I was present, would be sweeter to them. How greatly I congratulate these, the Lord is my witness, who hath condescended to tell what such, and such sort of servants deserve of His kindness.

Cyprian seems quite approving of these humble and meek lapsi, and doesn’t express disapproval at all of their certificates from the martyrs.

With your last statement: Are you supposing that indulgences are somehow “magical,” or that my drawing a connection between these libelli and indulgences must be “magical”?

Fantastic post! I had no idea about the origins of indulgences! 😀

Thanks! I’ve been pretty amazed by it, too. 🙂

I second that. Really interesting piece of history. I also like how you make the connection to the “communion of saints.”

Joseph, an interesting post, which adds greatly to my knowledge; thank you.

Can I try to clear something up here?

You write about the ‘temporal consequences’ of sin. So, if (Heaven forfend) I were to commit adultery and break up my family, and then repent, I can see that the damage I had done woud not be repaired thereby; for me these are the temporal consequences. I do not, in all honesty, see how a priest putting a penance on me and my doing it would do the slightest thing in temporal terms; those consequences would still be there, I would still have to live with them, and saying all the Hail Marys in the wide world would not change anything.

You seem to be saying the Church gives you a penance and the indulgence lifts it – that seems to me all about the letter of the law.

As I say, I am grateful for your efforts here, but this still looks ot me like the Church laying an extra yoke on people, and then wanting credit for removing it. Still, I am an ageing Baptist, so what do I know? 🙂

Thanks, Geoffrey. 🙂 It’s a good question. I hope to dig deeper into this sort of thing in my next post.

No, doing penance might not restore your family in that case; but the aim of the penance is more to restore your own soul than to “undo” the sin (although it’s wonderful when that can happen — our God is certainly a God who restores). I mean mainly the temporal conseqeunces to your own soul. Paul tells us that the sorrow of sin and the repentance it elicits leads to salvation (2 Corinthians 7:10), so working through the penance is designed to encourage and aid that contrition and repentance.

I’ve never been an adulterer or broken up a family, so I don’t know what kind of penance a priest might offer for that one — certainly it depends on the priest. I tend to favor tangible and meaningful penances like fasting and mandated works of charity rather than simply “five Hail Marys and three Our Fathers,” though I’ve found the latter is common for the sort of sin I am prone to (serious, but not as serious as breaking up a family). My pastor back in Oxford (Mississippi) gives me books and articles to read as penance, and sometimes when feeling especially contrite I’ve asked for something heavy like fasting and gotten it. You unfortunately can’t ask somebody to wear sackcloth and ashes in this day and age, but I think that would be appropriate!

Penances and indulgences were a lot more meaningful in the age of these canonical penalties and orders of public penitents, I think. Over the centuries Christians, in hardness of heart, lost patience with such practices, and the Church gradually dispensed with them in favor of indulgences, which during the Middle Ages came more and more to take the place of major works of penance. If you were an adulterer and placed under a sentence of penance, you would probably find it more palatable to make a pilgrimage to Rome or build a monastery (for which indulgences were offered) than live for seven years in sackcloth and ashes outside the communion of the Church.

So yes, outwardly, it appears to be concerned with the letter of the law — but the theological idea underlying indulgences, which I will get more into next time, is that these punishments can’t really be remitted just because the bishop or pope says so. Somebody has to pay that penalty in order for it to be dispelled. So who? As it is with the forgiveness of sin, we look first to Christ and His grace and the merits of the cross. But — and this is what I find really beautiful — because we are all united in the Body of Christ, we can in a sense bear each other’s sufferings. These martyrs I describe above offered up their sufferings to God and united theirs with Christ’s with the thought of easing the suffering of the lapsi. The Church eventually comes to speak of a “treasury of merit” from which the pope dispenses satisfaction to apply it to your penance and remit it by means of an indulgence — but what that really means is that somebody — or even everybody, all the righteous people of all the Church — offered up the satisfaction they performed so that united with Christ, they could bear the sufferings of those of us who hurt.

Most interesting, Joseph.

I must say I have an instinctive distrust of the idea of a treasury of ‘merit’, it smacks too much of schools and points and prizes. It is the way men think about these things, and it is natural that they should transfer that to God – but I fail to see Jesus behaving in such a manner or commending it.

I shall look forward though, to your further thoughts; you are a good apologist – a sincere compliment.

I don’t know man. Like I wrote before – make amends. The modern Protestants threw out the baby with the bathwater whenever they just say, “Jesus Saves” “Jesus Forgives” to every human sinful situation so the good ole historical church always has a thing of two to teach us . . . but making amends is the hard part. Sure sitting in sack cloth and ashes for a few years would be a pain . . . but nothing like continually showing faithfulness, monetary, emotional support and continually taking on the burden of the divorce before all family and friends after you committed adultery. THAT’S repentance. Never getting married again so you can always be available to the first family you screwed up – that’s repentance, that’s making amends. The point is I don’t need made up rules concerning sackcloth, I need someone to help me discern how I can REALLY make amends. We always need to be careful to see if religion is pointing us to Love God, Love Neighbor . . . or distracting us. This of course, happens to us all. Religion is always easier. Always. (forgive me for saying this) Burning on the blankety, blank stake in order to win the Sainthood of the Church is easier . . . than slogging faithfully thru life, making amends for each and every sin you commit . . . saying “I am wrong,” each and every time, asking forgiveness and giving it freely to others. Protestants may not keep it “Real” b/c they just say, “I’m forgiven” and move on . . . a lack of good religious practice if you will which you are teaching us about . . . The Ancient Faith folks may not keep it “Real” by thinking they’ve repented based on following the made up rules of religious folks that never truly got to the heart of what needed to be done . . . an over abundance of misguided religious practice if you will. Thanks for letting me blab. Love ya man.

Well, as I’ve told, the Church entirely agrees that we need to make amends. To quote the Catechism:

1459. Many sins wrong our neighbor. One must do what is possible in order to repair the harm (e.g., return stolen goods, restore the reputation of someone slandered, pay compensation for injuries). Simple justice requires as much. But sin also injures and weakens the sinner himself, as well as his relationships with God and neighbor. Absolution takes away sin, but it does not remedy all the disorders sin has caused (cf. Council of Trent [1551]: DS 1712). Raised up from sin, the sinner must still recover his full spiritual health by doing something more to make amends for the sin: he must “make satisfaction for” or “expiate” his sins. This satisfaction is also called “penance.” (2412; 2487; 1473)

1460. The penance the confessor imposes must take into account the penitent’s personal situation and must seek his spiritual good. It must correspond as far as possible with the gravity and nature of the sins committed. It can consist of prayer, an offering, works of mercy, service of neighbor, voluntary self-denial, sacrifices, and above all the patient acceptance of the cross we must bear. Such penances help configure us to Christ, who alone expiated our sins once for all. They allow us to become co-heirs with the risen Christ, “provided we suffer with him” (Rom 8:17; Rom 3:25; 1 Jn 2:1–2; cf. Council of Trent [1551]: DS 1690). (2447; 618)

A good confessor will give you a penance that involves, as much as possible, the making of amends with those who were wronged. It’s not all sackcloth and ashes. As I’ve written elsewhere in this thread, the penance is voluntary and for your spiritual good, for repairing your hurts, not just an empty display or religious show. That sort of thing is what Jesus explicitly spoke against (cf. Matthew 6:16). True repentance, true contrition, is what it’s all about. The aim of the penance is to get at that as best as possible, but in the end, a lot of it is left to us.

A few questions from the nosy Lutheran (so far, I think I’m following what you are saying).

If indulgences are concerned with the temporal, earthly consequences of sin on one’s own soul, why does it remit punishment in a non-earthly, non-temporal purgatory?

If forgiveness from God neither corrects the damage our sin does to others and does not correct the damage sin does to our own self, what does it do? If it restores our relationship with God (salvation), would it not remit the punishment as well? And if it doesn’t, is it really forgiveness or salvation? I see how this problem works itself out in human relationships did I kill someone, their family can choose to forgive me and restore their relationship with me, the relationship that I broke. But the authority over me and that family still calls for justice. With God, though, no one and no power/authority is higher, so if God forgives and restores the relationship, why is God still punishing? That’s not forgiveness at all–that’slike the family forgiving me, then going to the prosecutor and asking for the death sentence. It’s not really forgiveness.

You really are a good apologist for Rome.

No problem. I like nosy Lutherans. 🙂

If indulgences are concerned with the temporal, earthly consequences of sin on one’s own soul, why does it remit punishment in a non-earthly, non-temporal purgatory?

Well, first, purgatory is only concerned with temporal punishments to begin with — especially our attachments to sin and worldly things. Christ forgives our eternal punishment. Protestants make a distinction between justification and sanctification — and by that understanding, purgatory is to finish the job of sanctification — cleaning up the mess we’ve made of ourselves — if we don’t finish it in this life.

If forgiveness from God neither corrects the damage our sin does to others and does not correct the damage sin does to our own self, what does it do?

It remits the guilt of our sin, the eternal punishment, which would otherwise separate us from God for eternity.

If it restores our relationship with God (salvation), would it not remit the punishment as well?

That’s where we make a distinction between the eternal punishment, which we would suffer eternally if not for salvation, and temporal punishment, which is the consequences of our sin.

And if it doesn’t, is it really forgiveness or salvation?

Well, we will be saved and receive eternal life if we are in Christ. But that doesn’t take away all the consequences of our sin, all the pain we’re bound to suffer because of what we’ve done. God might, in His mercy, spare us a lot of that pain. But that temporal punishment, as suffering, is also salvific, sanctifying us (cf. Romans 8:17, 2 Corinthians 1:5-7, 1 Peter 4:13). God gives, or allows, the temporal punishment because suffering for our actions is ultimately for our own good — to teach us not to do it again; to grow in grace.

I see how this problem works itself out in human relationships did I kill someone, their family can choose to forgive me and restore their relationship with me, the relationship that I broke. But the authority over me and that family still calls for justice. With God, though, no one and no power/authority is higher, so if God forgives and restores the relationship, why is God still punishing? That’s not forgiveness at all–that’slike the family forgiving me, then going to the prosecutor and asking for the death sentence. It’s not really forgiveness.

The family could forgive you for murdering their loved one, but they would still consider it a grave injustice if the courts just turned you loose with your paying no penalty at all for your actions. The family would expect that you would serve an appropriate prison sentence.

During my conversion, I really struggled with the concept of purgatory — see this confusing post (but don’t take it to be an expression of correct doctrine), in which I was struggling to get it and really didn’t. But I was really troubled all of a sudden, too, of the thought that a murderer who is forgiven by Christ suddenly has no penalty to pay at all.

You really are a good apologist for Rome.

Why thank you. 🙂 I am trying and praying.

I learned a lot from your post Joseph: well done. Looking forward to your next. This is probably one of the most ticklish of subjects when apologizing the faith to Protestants who have not a sense of these things at all.

Thanks. I am glad I’m able to shed some light. Yes, these distinctions are very fine, and taken on their face, offend the Protestant sensibilities. I admit I have struggled with them, too — especially understanding how temporal punishment works; it does seem, coming from my Protestant background, that Jesus should forgive all the punishment. But if we understand the temporal punishment as what it is we’re bound to suffer anyway because of our sin — because of the very nature of sin, and because it hurts us and others — then yes, it is pretty clear that Jesus doesn’t take all of that away. We are bound to suffer something for our wrongs; that’s just the way God created the world. And clearly it’s something He allows.

I love your explanations and your insight into this topic. It (indulgences) tends to confuse many of our brothers and sisters from other traditions. I think you have made it more understandable to many. God bless.

Thank you so much, brother. God bless you, too.

🙂

Pingback: Substitutionary Commotion | The Lonely Pilgrim

A couple of months ago, I was miss led by false teachings, false versions of Christianity which were robbing me of joy, and robbing others who I hope to eventually impact by serving Jesus Christ and sharing the supremacy of Christ in my lifetime. I wrote a blog-post on my blog, that I deleted recently.. but in it, I attacked the Catholic faith, and I have come to the conclusion now that you can’t experience the fullness of Jesus Christ anywhere else other than the Catholic (Universal) church. While there are many misconceptions/rumors and all sorts of things that Protestant’s will use, it’s only natural to happen… such as wars in the world are only natural events that will and have occurred over time in this world. The cool thing about the Catholic faith is there is such a rich history to it, and many Saints who were known to be the first Christians (when the church) was of existence are known to have been defenders of Christianity’s teachings against other religions. I feel well pleased and honored to share with you, my dear brother in Christ, Joseph Richardson, that I Thomas Brunt, feel led, and deeply drawn into the life of the priesthood, and who knows, maybe Christ could be calling me to give up my life to serve him. I will keep you posted on my journey in the Catholic faith, and my journey in discerning God’s will for me as I figure out what God has in store for me.

God bless you, may God keep you, and may the peace of Christ rule and dwell richly among you, forever and ever. Amen.

Thanks be to God! Another man to add to my growing prayer list for those discerning the priesthood.

Praise God, brother. 🙂 Please do keep me posted. I will keep you posted on my journey of discernment, too.