The Sacrifices of Melchizedek, Abel, and Abraham. Mosaic from the Basilica of Sant’Apollinare in Classe, Ravenna.

We have examined how the word “priest” in English is actually a translation of the New Testament Greek word πρεσβύτερος [presbyteros] (“elder”), etymologically distinct from the concept of a ἱερεύς [hiereus] or sacerdos, the sacrificing minister of the Old Testament; and thus “priest” is an appropriate title for the office of Christian ministry. We have shown how Jesus, in instituting a New Covenant, appointed the Apostles ministers of His New Covenant, and they in turn ordained bishops, priests, and deacons to continue in their ministry. We have examined how these early ministers understood themselves to be ministers of the New Covenant in some sense analogous to the priests (sacerdotes) of the Old Covenant, and how even the Old Testament prophets foretold that the coming New Covenant of the Messiah would be served by priests.

But another, crucial aspect of the term priest (Latin sacerdos or Greek ἱερεύς [hiereus] or Hebrew כֹּהֵן [cohen]), essential to the understanding of that office in both Judaism and in every other ancient culture to which the term was applied, is that a priest makes sacrifices. In the tradition of the Church, some early authors came eventually to refer to presbyters synonymously as sacerdotes or ἱερεῖς [hiereis].* In asking whether it is appropriate to call Christian ministers priests, it is thus important to ask whether they make sacrifices, and whether the earliest Christians understood their office as such.

* I’m still working on this research, which is complicated by the fact that I don’t have very easy access to the source languages, and that at a certain point in even the Protestant-edited Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers (Schaff and Wace), the words presbyter, sacerdos, and ἱερεύς all begin being translated as “priest” without qualification. So far I’ve found that Tertullian makes reference to the Christian ministry as sacerdotalia munera (“priestly services”) (De praescriptione hereticorum XLI, c. A.D. 200). Cyprian very frequently refers to Christian ministers as sacerdotes (c. A.D. 250) who make sacrifices. Augustine casually refers to a sacerdotem tuum, quendam episcopum nutritum in ecclesia, “a priest [of God], a certain bishop brought up in the Church” (Confessions 3.12). In the East, Basil the Great calls the Christian minister a ἱερεύς, to be distinguished from a layman (λαϊκὸς) (Letter XLIV, c. A.D. 370). I will continue to work on this.

But an important preliminary to this question is whether the idea of sacrifice is even present in the New Testament.. The answer will hopefully seem obvious to most Christians: The idea of sacrifice, and sacrificial language, in fact pervades the New Testament.

A. Sacrifice in the New Testament

1. A Sacrifice of Praise

As our critics have thus far noted in response to previous posts, the New Testament presents that all the Christian faithful, the whole people of God, are called to make spiritual sacrifices. Thus Paul urges:

I appeal to you therefore, brethren, by the mercies of God, to present your bodies as a living sacrifice, holy and acceptable to God, which is your spiritual worship. (Romans 12:1)

And Peter calls:

Come to him, to that living stone, rejected by men but in God’s sight chosen and precious; and like living stones be yourselves built into a spiritual house, to be a holy priesthood, to offer spiritual sacrifices acceptable to God through Jesus Christ. … [For] you are a chosen race, a royal priesthood, a holy nation, God’s own people, that you may declare the wonderful deeds of him who called you out of darkness into his marvelous light. (1 Peter 2:4–5,9)

The author of the Epistle to the Hebrews likewise presents Christian worship and even the Christian life as sacrifice to God:

Through him then let us continually offer up a sacrifice of praise to God, that is, the fruit of lips that acknowledge his name. Do not neglect to do good and to share what you have, for such sacrifices are pleasing to God. (Hebrews 13:15–16, cf. Hebrews 12:28-29)

The language of offering and sacrifice in fact does pervade the New Testament, especially in the writings of Paul (e.g. Philippians 2:17, 4:18, Romans 15:16. This is understandable and fitting given the Jewish foundations of the Christian faith, its roots in the Old Testament, and the Pharisaical education of Paul. Most of all, it is fitting given the example of the Author and Perfecter of our faith, Jesus Christ.

2. Jesus’s Sacrifice

Matthias Grunewald, Crucifixion, from Grunewald, Crucifixion, from Tauberbischofsheim altarpiece, c. A.D. 1524.

The New Testament is also clear in presenting the death of Jesus on the Cross as a sacrifice for our redemption, the gift of Himself out of love for us.

Walk in love, as Christ loved us and gave himself up for us, a fragrant offering and sacrifice to God. (Ephesians 5:2)

The Epistle to the Hebrews elaborates on this understanding throughout the letter:

[Jesus] has no need, like those high priests [of the Old Covenant], to offer sacrifices daily, first for his own sins and then for those of the people; he did this once for all when he offered up himself. (Hebrews 7:27)

Paul in particular explicitly presents Christ as our paschal lamb, the fulfillment of the Jewish Passover, a new sacrifice to institute a new covenant:

Cleanse out the old leaven that you may be a new lump, as you really are unleavened. For Christ, our paschal lamb, has been sacrificed. (1 Corinthians 5:7)

And the Evangelists — especially John — shared this understanding. John presents John the Baptist’s exclamation at Jesus’s approach:

The next day [John] saw Jesus coming toward him, and said, “Behold, the Lamb of God, who takes away the sin of the world!” (John 1:29)

Peter shares this understanding (1 Peter 1:19) as does John the Revelator (Revelation 5:6, etc.). It appears that the Synoptic Gospels might also allude to it:

Then came the day of Unleavened Bread, on which the passover lamb had to be sacrificed. So Jesus sent Peter and John, saying, “Go and prepare the passover for us, that we may eat it.” (Luke 22:7–8, cf. Mark 14:12)

The mention of the lamb and eating it is curious: for the lamb is not mentioned again. And in fact this was the day on which Jesus, the Passover lamb, had to be sacrificed.

B. The Eucharist as Sacrifice

1. The Connection between the Last Supper and the Crucifixion

Juan de Juanes, Última Cena, c. A.D. 1562 (Wikipedia).

Many tomes have been written on the theology of the Eucharist; I cannot but begin to nick the surface here. But this seems to be the very burning heart of the disagreement between traditional Christians and Protestants regarding the priesthood: All seem to agree that Jesus gave Himself up as a sacrifice for us; but what is the relationship of His sacrifice on the Cross to His presentation of the Lord’s Supper? What is the meaning of His commandment to do this in memory of Him? What is the role of Christian ministers in this ritual?

Scripture itself presents that there is an essential connection between the Lord’s offering of bread and wine at supper that night and His Crucifixion the next day. It is clear, first of all, that the Lord’s Last Supper was the Passover meal (Matthew 26:17-19, Mark 14:12-16, Luke 22:7-13, John 13:1-2ff.). Jesus alluded, more clearly than He had up to that point, to His impending death (Matthew 26:2, etc.). At supper, he called out the one who was to betray him (Luke 22:21–22, etc.). After the meal, the drama of His Passion played out in His agony in the garden (Matthew 26:30–46). All of this, it might be argued, is simply foreshadowing, allusion to what is about to happen. But the meat of the matter — the subject of so much disagreement and debate and controversy — are His words and actions at the meal itself:

And as they were eating, he took bread, and blessed, and broke it, and gave it to them, and said, “Take; this is my body.” And he took a cup, and when he had given thanks he gave it to them, and they all drank of it. And he said to them, “This is my blood of the covenant, which is poured out for many. Truly, I say to you, I shall not drink again of the fruit of the vine until that day when I drink it new in the kingdom of God.” (Mark 14:22–25)

Now as they were eating, Jesus took bread, and blessed, and broke it, and gave it to the disciples and said, “Take, eat; this is my body.” And he took a cup, and when he had given thanks he gave it to them, saying, “Drink of it, all of you; for this is my blood of the covenant, which is poured out for many for the forgiveness of sins. I tell you I shall not drink again of this fruit of the vine until that day when I drink it new with you in my Father’s kingdom.” (Matthew 26:26–29)

And when the hour came, he sat at table, and the apostles with him. And he said to them, “I have earnestly desired to eat this passover with you before I suffer; for I tell you I shall not eat it until it is fulfilled in the kingdom of God.” And he took a cup, and when he had given thanks he said, “Take this, and divide it among yourselves; for I tell you that from now on I shall not drink of the fruit of the vine until the kingdom of God comes.” And he took bread, and when he had given thanks he broke it and gave it to them, saying, “This is my body which is given for you. Do this in remembrance of me.” And likewise the cup after supper, saying, “This cup which is poured out for you is the new covenant in my blood.” (Luke 22:14–20)

Ugolino di Nerio, The Last Supper (A.D. 1324) (Wikimedia).

Discussions about the Real Presence of Christ in the Eucharist tend to hinge, often fruitlessly, on the word is: “This is my body.” But I would like to draw attention to the tense of this verb, and to the tenses of His surrounding statements: He declares that the bread which He presents is His body, present tense, which is given, present tense, for us. Regardless of disagreements about what the bread and wine are — whether they are His Body and Blood as he said, or mere symbols or representations — His words indicate that what He was giving was being given in that instant. This was not “My Body, which I will give for you when I suffer,” or “My Blood, which will be poured out for you this day”: For Jesus, speaking at the Last Supper, the moment of His suffering had come. Even as most Passion plays present it, the events of the Cenacle to the Cross to the Tomb can be understood as one continuous movement.

Protestant opponents to the traditional understanding of the Eucharist (as our commenter) tend to get hung up on temporal and chronological aspects — calling it “science fiction” to suggest that Jesus could give His body up for us “before going to Calvary.” But this view seems to ignore the plainly sacrificial language of what Jesus was doing. Jesus did, Scripture insists, offer Himself up as a sacrifice for us. And in His own words at the Last Supper, he then and there gave Himself for us: “This is my body which is given for you.”

Jesus’s words consciously echo the words of institution of the Mosaic covenant:

And likewise the cup after supper, saying, “This cup which is poured out for you is the new covenant (διαθήκη) in my blood.” (Luke 22:20)

And Moses took the blood and threw it upon the people, and said, “Behold the blood of the covenant (Septuagint διαθήκη) which the LORD has made with you in accordance with all these words.” (Exodus 24:8)

Even the author of the Epistle to the Hebrews explicitly acknowledges and relates this essential connection between the Lord’s sacrifice and His words of institution at the Last Supper:

When Christ appeared as a high priest of the good things that have come, then through the greater and more perfect tent (not made with hands, that is, not of this creation) he entered once for all into the Holy Place, taking not the blood of goats and calves but his own blood, thus securing an eternal redemption. … Therefore he is the mediator of a new covenant (διαθήκη), so that those who are called may receive the promised eternal inheritance, since a death has occurred which redeems them from the transgressions under the first covenant (διαθήκη). For where a will (διαθήκη) is involved, the death of the one who made it must be established. For a will (διαθήκη) takes effect only at death, since it is not in force as long as the one who made it is alive. Hence even the first covenant (διαθήκη) was not ratified without blood. For when every commandment of the law had been declared by Moses to all the people, he took the blood of calves and goats, with water and scarlet wool and hyssop, and sprinkled both the book itself and all the people, saying, “This is the blood of the covenant (διαθήκη) which God commanded you.” (Hebrews 9:11–12,15-20)

Our commenter attempted to make an argument that Christ’s words of institution at the Last Supper must have been only symbolic and not essentially connected to the Crucifixion at all, since His words are here presented as a will or testament, and no death had yet occurred at the Last Supper, etc. But this is clearly wrongheaded, for the passage itself declares that the New Covenant is in effect, since a death has occurred which redeems us.

The author of Hebrews thus presents Christ’s words of institution (His own declaration that His blood was a New Covenant) and His sacrificial death as essentially the same act: the declaration of the covenant and its ratification by blood. Just so, Moses’s institution of the Old Covenant in Exodus involved separate elements of the same act of institution: offering blood, words of institution (Exodus 24:8), and a meal between the parties of the covenant (Exodus 24:11). Such is the protocol of covenant in the ancient world: and it was played out again by Jesus in the Last Supper and the Crucifixion as a single act.

The chronology of these acts is thus irrelevant: Jesus’s institution of the covenant at the Last Supper was the presentation of His death as a sacrifice, using explicitly sacrificial and covenantal language. Jesus Himself told us that in the death of His body, He was offering Himself as a sacrifice for the forgiveness of our sins; that in His blood, He was instituting a New Covenant for us. He offered the sacrifice of His body at the Passover supper, and gave it to his disciples to eat as the new Passover lamb (1 Corinthians 5:7). The very idea that Jesus was our paschal lamb as Paul expresses depends on the understanding that Jesus was sacrificed and presented in place of the lamb at the Passover meal. Scripture is thus clear in this understanding.

Dr. Brant Pitre’s study of the Jewish roots and context of the Eucharist casts a brilliant light on this reality. A valuable outline is available online: “The Fourth Cup and the New Passover.” (See also his audio lesson.) Even more fruitful is his book, Jesus and the Jewish Roots of the Eucharist. A quote in summary from the outline:

1. By vowing not to drink the final cup of the Last Supper (Luke 22:18), Jesus extended his last Passover meal to include his own suffering and death.

2. By praying three times in Gethsemane for the “cup” to be taken from him (Matthew 26:36-46), Jesus revealed that he understood his own death in terms of the Passover sacrifice.

3. Jesus also transformed the Passover sacrifice. In the old Passover, the sacrifice of the lamb would come first, and then the eating of its flesh. But in this case, because Jesus had to institute the new Passover before his death, he pre-enacted it, as both host of the meal and sacrifice.

4. Most important of all, by waiting to drink the fourth cup of the Passover until the very moment of his death (John 19:28-29), Jesus united the Last Supper to his death on the cross. By refusing to drink of the fruit of the vine until he gave up his final breath, he joined the offering of himself under the form of bread and wine to the offering of himself on Calvary. Both actions said the same thing: “This is my body, given for you” (Luke 22:19). In short, by means of the Last Supper, Jesus transformed the Cross into a Passover, and by means of the Cross, he transformed the Last Supper into a sacrifice.

2. “Do This In Memory of Me”

Tintoretto, The Last Supper, A.D. 1592-1594 (Wikipedia).

So Scripture is clear that at the Last Supper, Jesus presented His Body and Blood as a sacrifice. But what did He mean when He commanded His Apostles to “Do this in remembrance of me”? Do what, exactly? To whom was this command addressed? And if Jesus’s presentation was a sacrifice, what would be the character of others’ doing it in His memory?

Doing this was important enough to St. Paul to quote in full the words of institution and give specific instruction about what was to be done and why:

For I received from the Lord what I also delivered to you, that the Lord Jesus on the night when he was betrayed took bread, and when he had given thanks, he broke it, and said, “This is my body which is for you. Do this in remembrance of me.” In the same way also the cup, after supper, saying, “This cup is the new covenant in my blood. Do this, as often as you drink it, in remembrance of me.” For as often as you eat this bread and drink the cup, you proclaim the Lord’s death until he comes. (1 Corinthians 11:23–26)

Thus it is clear that the Apostles understood Jesus meant specifically to do this: to reenact the offering of Himself at the Last Supper, and to give the Christian faithful this food to eat (John 6:34). If the Lord’s presentation of Himself at the Last Supper was a sacrifice, then the re-presentation — which He commanded His Apostles to do — is the re-presentation of a sacrifice.

That Paul understood the re-presentation of the Eucharist to also be a sacrifice is also evident — for he explicitly compares the Eucharistic table to an altar of sacrifice, and opposes the food of the Eucharistic table to food offered in sacrifice to idols:

Therefore, my beloved, shun the worship of idols. I speak as to sensible men; judge for yourselves what I say. The cup of blessing which we bless, is it not a participation in the blood of Christ? The bread which we break, is it not a participation in the body of Christ? Because there is one bread, we who are many are one body, for we all partake of the one bread. Consider the people of Israel; are not those who eat the sacrifices partners in the altar? What do I imply then? That food offered to idols is anything, or that an idol is anything? No, I imply that what pagans sacrifice they offer to demons and not to God. I do not want you to be partners with demons. You cannot drink the cup of the Lord and the cup of demons. You cannot partake of the table of the Lord and the table of demons. (1 Corinthians 10:14–21)

Paul thus implies that if pagans offer their sacrifices to demons and not to God, and in eating of the sacrifices become partners with demons, Christians do make their sacrifices to God, and in eating of them, have participation (Greek κοινωνία [koinōnia], literally “communion”) in the Body and Blood of Christ.

3. Testimony from Tradition

Scripture is thus clear in understanding the re-presentation of the Eucharist as a sacrifice in some sense: a re-presentation of Christ’s own sacrifice. That this is the correct interpretation of Scripture can be verified in the earliest understandings of the Church after Scripture. Our commenter accuses that we must “go outside Scripture” to support the view that the Eucharist is a sacrifice, but on the contrary, all the support that is necessary is already evident in Scripture; looking beyond Scripture only further confirms the truth we find in Scripture. We read in the Didache, which many scholars reasonably date to circa A.D. 70, within the Apostolic age itself:

And on the Lord’s day of the Lord assemble yourselves together and break bread (Revelation 1:10); and give thanks (Greek εὐχαριστήσατε [eucharistēsate]) after having confessed also your transgressions, that your sacrifice may be pure. And let not any man that is at variance with his fellow come together with you until they be reconciled, that your sacrifice be not polluted. For this [sacrifice] is that which was spoken of by the Lord: In every place and time offer unto me a pure sacrifice (Malachi 1:11), for I am a great King, saith the Lord; and My Name is wonderful among the Gentiles. (Didache XIV, from G. C. Allen, trans., The Didache or The Teaching of the Twelve Apostles [London: The Astolat Press, 1903])

The value of this testimony is not that our understanding of the Eucharist as a sacrifice depends on it (in fact, I wasn’t even aware of these passages before I wrote the above sections of the article), but that it demonstrates that the earliest Christians, taught by the Apostles themselves, shared the same understanding we now derive from Scripture. It also directly refutes the arguments our commenter has already advanced, that the Council of Trent innovated the Church’s understanding of the Eucharist as sacrifice, that “no Christian in the 1,600 years prior to Trent” held such an understanding. Not only is the understanding of the Eucharist as sacrifice expressed in Scripture, but the earliest Christians, taught by the oral teaching of the Apostles, held and expressed this same understanding.

Opposition from Hebrews?

As clear as Christ’s command to re-present His sacrifice, the author of the Epistle to the Hebrews makes just as clear that Christ’s sacrifice was made once for all; that Christ, our High Priest, has no need to offer repeated sacrifices; that He does not suffer repeatedly (Hebrews 7:27, 9:26). We know that Scripture cannot contradict itself. Thus it is clear that the re-presentation of Christ’s sacrifice which He commanded cannot be a repetition of His sacrifice, or a re-sacrificing of Christ; rather it must be a presenting again of the same once and for all sacrifice.

Rather than an argument against the Eucharist, as Protestant opponents insist to read it, Hebrews thus becomes a treatise on the Eucharist, an explanation to especially Jews that Jesus’s one sacrifice, and the sacrifices which Christians make in memory of Him, were not the kind of repeated and inefficacious sacrifices presented again and again in the Old Testament, but indeed one final, once and for all sacrifice for our redemption and salvation. Nothing about the argument of Hebrews nullifies or eliminates Christ’s command to do this in memory of Him; rather, it is only with His command in mind, and the understanding that this was practiced regularly as the central element of Christian worship (Acts 2:42,46), that the Book of Hebrews can be read with benefit in its proper context.

C. Ministers of the New Covenant

1. Office and Authority

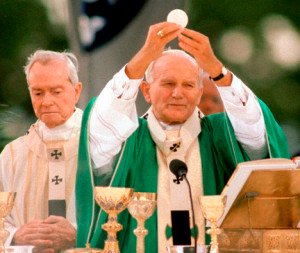

St. John Paul II celebrating Mass, New Orleans, 1987. (CatholicVote.org).

So, then, as Scripture teaches, Jesus, through the sacrifice of His Body and Blood on Calvary, presented at the Last Supper, Jesus instituted a new covenant. The Book of Hebrews especially elaborates on this idea of the new covenant. Paul too understands this idea, identifying himself and his associates in ministry as “ministers of the New Covenant” (2 Corinthians 3:4–6).

Scripture is not explicit in declaring that the ministers of the New Covenant make sacrifices, and it intentionally shies away from calling them ἱερεῖς [hiereis] or sacerdotes. But the implications of Scripture are clear: Jesus offered Himself as a sacrifice for us, becoming our High Priest (ἀρχιερεύς [archiereus]); he presented this sacrifice through the signs of bread and wine at the Last Supper; he commanded His Apostles to “do this in memory of me” — to re-present the sacrifice He had presented. What would they then be presenting, if not a sacrifice?

Indeed, as shown above, and as is evident throughout the literature of the Early Church, the earliest Christians did understand the presentation of the Eucharist to be a sacrifice. Once again, this testimony is offered in verification of the truths already revealed in Scripture:

Being vehemently inflamed by the word of His calling, we are the true high priestly race of God, as even God Himself bears witness, saying that in every place among the Gentiles sacrifices are presented to Him well-pleasing and pure (Malachi 1:11). Now God receives sacrifices from no one, except through His priests. Accordingly, God, anticipating all the sacrifices which we offer through this name, and which Jesus the Christ enjoined us to offer, i.e., in the Eucharist of the bread and the cup, and which are presented by Christians in all places throughout the world, bears witness that they are well-pleasing to Him. (Justin Martyr, Dialogue with Trypho 116–117, c. A.D. 160)

Justin here makes reference to God’s priests, especially in juxtaposition to the Jewish priests of the Old Covenant, whom he says God now rejects. Justin thus seems to understand that even though all Christians are the “high priestly race of God,” there are nonetheless some who offer the sacrifices.

Who is it, then, who offers the sacrifices? To whom was Jesus giving the commandment when he said to “Do this in memory of Him”? As an Evangelical, I would have answered “to all Christians,” and this seems to be a common response (as there is a tendency in especially Evangelicalism to read all Scripture as if every statement were a direct address to the individual Christian). But most obvious to me now, the closed group to whom Jesus was actually speaking was His Twelve Apostles.

Baptists do it, too. (Bible Baptist Church, New Port Richey, Florida)

There are practical reasons to think that Jesus was offering a charge to His ministers and not to all Christians, as are played out in even Protestant churches. Just as Jesus presided over the Last Supper, the re-presentation of such must also be presided over: there must be someone to speak and offer the sacrifice, someone to operate in the place of Christ. By their very position, this role usually falls to pastors.

But in traditional Christianity, the charges of Jesus to His Apostles, not only in the ministry of the Eucharist but in the very roles of teaching and pastoring, are understood not just in terms of practicality but of office and authority. As we have already discussed, Jesus did appoint His Apostles to an office of ministry. In His charges to speak in His name and carry His message throughout the world — and to do “Do this in memory of Him” — He authorized them to carry out this ministry; to be His representatives (Matthew 10:40, Luke 10:16), His ambassadors (2 Corinthians 5:20).

2. Apostolic Succession

As we have discussed, Jesus appointed the Apostles to an ordained office of ministry, with specific duties and authorities (Mark 3:13-18, Matthew 10, Luke 9:1-6, John 20:19-23, etc.). The Apostles then appointed presbyters and bishops to continue in their ministry after them:

And when they had appointed presbyters for them in every church, with prayer and fasting they committed them to the Lord in whom they believed. (Acts 14:23)

This is why I left you in Crete, that you might amend what was defective, and appoint presbyters in every town as I directed you. (Titus 1:5)

That this office and charge was only committed to another by the Apostles themselves or others in the order of presbyters is also evident:

Command and teach these things. Let no one despise your youth, but set the believers an example in speech and conduct, in love, in faith, in purity. Till I come, attend to the public reading of scripture, to preaching, to teaching. Do not neglect the gift you have, which was given you by prophetic utterance when the council of presbyters (πρεσβυτέριον [presbyterion]) laid their hands upon you. Practice these duties, devote yourself to them, so that all may see your progress. Take heed to yourself and to your teaching; hold to that, for by so doing you will save both yourself and your hearers. (1 Timothy 4:11–16)

Hence I remind you to rekindle the gift of God that is within you through the laying on of my hands. (2 Timothy 1:6)

Likewise Paul warned Timothy to take care with whom he ordained to the ministry:

Do not be hasty in the laying on of hands, nor participate in another man’s sins; keep yourself pure. (1 Timothy 5:22)

But nonetheless Timothy was charged to ordain others to continue in his own ministry:

What you have heard from me before many witnesses entrust to faithful men who will be able to teach others also. (2 Timothy 2:2)

Thus Scripture presents the fundamental idea of apostolic succession: that the Apostles appointed ministers to continue after them, who likewise should appoint ministers to continue after them. And thus it was understood by the Early Church, as the earliest testimony of those who came after the Apostles bears:

[The Apostles] preached from district to district, and from city to city, and they appointed their first converts, testing them by the Spirit, to be bishops and deacons of the future believers. … Our Apostles also knew through our Lord Jesus Christ that there would be strife for the title of bishop. For this cause, therefore, since they had received perfect foreknowledge, they appointed those who have been already mentioned, and afterwards added the codicil that if they should fall asleep, other approved men should succeed to their ministry. We consider therefore that it is not just to remove from their ministry those who were appointed by them, or later on by other eminent men, with the consent of the whole Church, and have ministered to the flock of Christ without blame, humbly, peaceably, and disinterestedly, and for many years have received a universally favourable testimony. For our sin is not small, if we eject from the episcopate those who have blamelessly and holily offered its sacrifices. (Clement of Rome, 1 Clement XLII, XLIV, c. A.D. 70s; from The Apostolic Fathers, ed. Kirsopp Lake, vol. 1, The Loeb Classical Library [Cambridge MA; London: Harvard University Press, 1912–1913])

Clement thus testifies to the earliest Church’s understanding of apostolic succession — and also, to add to our discussion here, confirms that offering sacrifices was part of the office of the episcopate (i.e. the office of bishop).

Ignatius of Antioch likewise confers, clarifying that offering the Eucharist was the express authority of the bishop and of presbyters he might appoint:

See that you all follow the bishop, as Jesus Christ follows the Father, and the presbytery as if it were the Apostles. And reverence the deacons as the command of God. Let no one do any of the things appertaining to the Church without the bishop. Let that be considered a valid Eucharist which is celebrated by the bishop, or by one whom he appoints. Wherever the bishop appears let the congregation be present; just as wherever Jesus Christ is, there is the Catholic Church. It is not lawful either to baptise or to hold an “agapé” without the bishop; but whatever he approve, this is also pleasing to God, that everything which you do may be secure and valid. (Ignatius of Antioch, Epistle to the Smyrnaeans VIII, c. A.D. 107; from The Apostolic Fathers, ed. Lake)

Thus if we accept that specific duties of ministry were the charge of the offices of ministry to which Jesus appointed the Apostles and to which they appointed other faithful men, then it follows that offering the sacrifice of the Eucharist — which Scripture presents as a central element of Christian ministry and worship — would have been a key component of those offices, and not a casual celebration which any believer could conjure at his whim. The earliest testimony of the Apostolic Fathers confirms that this was the case, as it has been understood throughout Christian history and tradition.

Conclusion

This is the outline of the doctrine presented by Scripture: Jesus offered Himself as a sacrifice to God for our redemption (Ephesians 5:2, etc.); He presented this sacrifice at the Last Supper (Luke 22:19, etc.) and perfected it on the Cross (John 19:30, etc.). He commanded His Apostles to “Do this in memory of Him” (Luke 22:19) — that is, to re-present the sacrifice which He had presented. This office was carried forth by those Apostles and by others whom they appointed to their ministry. That these were the doctrines which Christ taught, which the Apostles communicated, and which they committed to Scripture, is confirmed by the fact that this is the way the earliest Christians received and understood such teaching.

Thus we have an order of ministers, called by God and ordained to an office, to serve the New Covenant of God (2 Corinthians 3:4–6). Thus even the Apostle Paul saw this ministry to be analogous to the priesthood of the Old Covenant (Romans 15:16). The prophets of the Old Testament foresaw that God would call a new order of priests in service of His New Covenant, to offer sacrifices forever (Isaiah 61:6, 66:18, 20–21; Jeremiah 33:17–18, 22). Jesus commanded His ministers to re-present His sacrifice — and in so doing what they presented was a sacrifice. The order of Christian ministers in service of Christ’s New Covenant thus do make sacrifices, in some mysterious sense that does not call into question the oneness or finality of Christ’s once and for all sacrifice. Christian ministers can thus rightly be called sacerdotes — priests — in the service of Christ.

Over the generations to come, through prayerful reflection and close study of the Scriptures, the Church’s understanding of the Eucharist, the Sacraments, and the priesthood deepened and expanded. Priests, teachers, and theologians would explore the mystery of faith, the sacrifice of the Eucharist, to attempt to understand and explain its beauty, majesty, and truth. Church Fathers such as Cyril, Chrysostom, Ambrose, and Augustine offered forth elaborate theological treatises, practical instructions, and glorious panegyrics in praise of the Eucharist — but these were only the flowering forth of the core truths of the faith, which had been present, in Scripture and Tradition, from the beginning. Our recent commenters here have raged against the “nonsense” they can cite from the Council of Trent and other late promulgations of doctrine, arguing that such elaborations of doctrine were nowhere found in Scripture — but attacking a mere flourish is as ineffective in refuting the core truths of traditional Christianity as plucking leaves from a tree. The outline, the seed, is here, presented in Scripture and verified by the testimony to Tradition.