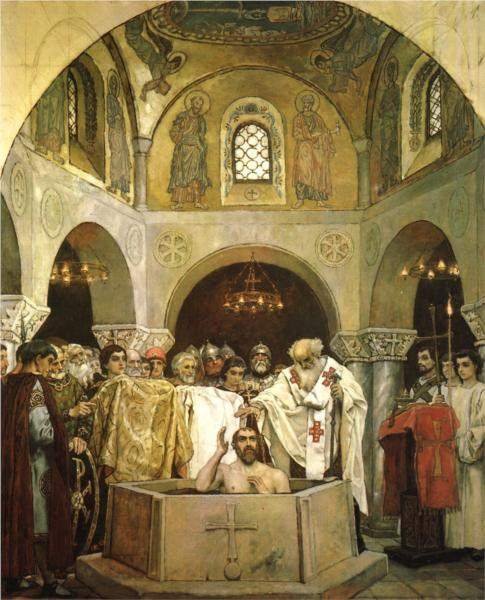

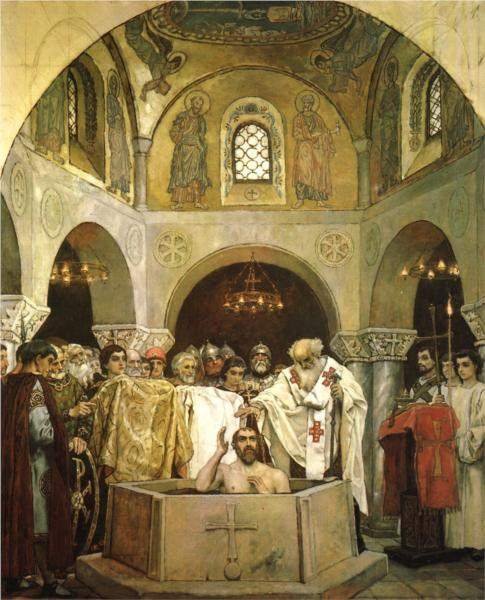

The Baptism of Prince Vladimir (1890), by Viktor Vasnetsov (WikiPaintings).

(Part of an in-depth series on Baptism. Part 1. Part 2.)

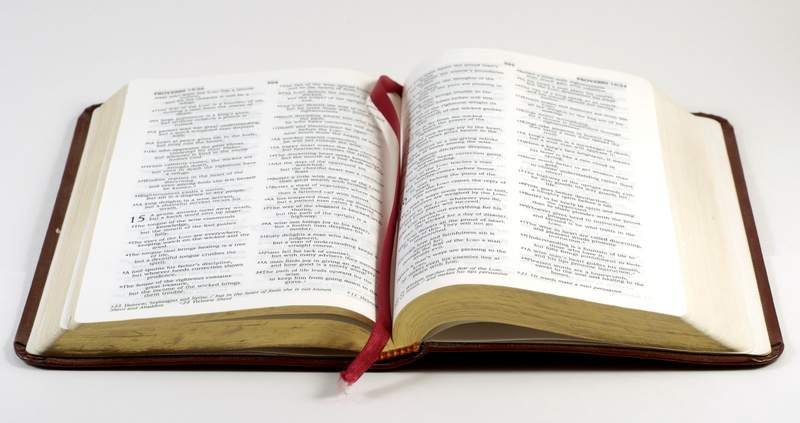

When we left off, we were examining the Baptist view of Baptism, that it is merely a symbol, a sign of a work of grace that has already taken place in the believer by faith, an ordinance of the Church, not necessary for grace or salvation, but ordained by Lord and done in obedience to Him.

This understanding seems to derive not so much from the interpretation of any particular passage of Scripture that would indicate Baptism was purely symbolic, but a general interpretation of all passages of Scripture pertaining to Baptism as symbolic. The whole argument that Baptism is not sacramental and does not in itself accomplish regeneration in a believer appears to rest on three cases in which believers were apparently regenerated prior to and apart from Baptism: (1) the repentant thief on the cross (Luke 23:39–43), (2) Saul’s dramatic conversion on the road to Damascus (Acts 9), and (3) the fall of the Holy Spirit on the gathered Gentiles at the house of Cornelius (Acts 10:24–48). But do these cases represent the ordinary working of the Holy Spirit, or were they exceptions? To answer this, let us delve into the Scriptures.

The Repentant Thief

One of the criminals who were hanged railed at him, saying, “Are you not the Christ? Save yourself and us!” But the other rebuked him, saying, “Do you not fear God, since you are under the same sentence of condemnation? And we indeed justly; for we are receiving the due reward of our deeds; but this man has done nothing wrong.” And he said, “Jesus, remember me when you come into your kingdom.” And he said to him, “Truly, I say to you, today you will be with me in Paradise.” (Luke 23:39-43)

The Crucifixion (1456), by Vincenzo Foppa (Wikimedia).

So the thief repented, which we know was a work of grace. And we know that the thief died, and that when he did, Jesus welcomed him into His kingdom. In this sense, he certainly received salvation without the necessity of Baptism in water. But does this case demonstrate definitively that the thief was regenerated, his sins washed away and his soul born again in Christ, the way Christian believers ordinarily are, prior to his death? Perhaps he was; perhaps he wasn’t; but this passage doesn’t indicate it.

The Catholic Church believes that Baptism by blood — in which one suffers death for the sake of the faith — can bring the fruits of the Sacrament of Baptism. Whether this is what happened here or not — it is self-evident that if ever there were an exceptional case of salvation in the Gospels, it was that of the repentant thief, who was saved at the very divine fiat of Jesus.

Paul on the Road to Damascus

The Conversion of St. Paul (1767), by Nicolas-Bernard Lepicie (Wikimedia).

Now as [Saul] journeyed he approached Damascus, and suddenly a light from heaven flashed about him. And he fell to the ground and heard a voice saying to him, “Saul, Saul, why do you persecute me?” And he said, “Who are you, Lord?” And he said, “I am Jesus, whom you are persecuting; but rise and enter the city, and you will be told what you are to do.” …

Ananias departed and entered the house. And laying his hands on him he said, “Brother Saul, the Lord Jesus who appeared to you on the road by which you came, has sent me that you may regain your sight and be filled with the Holy Spirit.” And immediately something like scales fell from his eyes and he regained his sight. Then he rose and was baptized. (Acts 9:3-6, 17-18)

In the case of Saul, we see that Jesus intervened directly and tangibly in his life, stopping him in his tracks and turning his life around. But it is not at all clear here that Saul was regenerated or received the Holy Spirit prior to his Baptism.

In fact, elsewhere we find reason to believe that he was not. In the second telling of Saul’s conversion, as Paul presents his defense before the Jews, different words are given to Ananias:

“And one Ananias, a devout man according to the law, well spoken of by all the Jews who lived there, came to me, and standing by me said to me, ‘Brother Saul, receive your sight.’ And in that very hour I received my sight and saw him. And he said, ‘The God of our fathers appointed you to know his will, to see the Just One and to hear a voice from his mouth; for you will be a witness for him to all men of what you have seen and heard. And now why do you wait? Rise and be baptized, and wash away your sins, calling on his name.’ (Acts 22:12–16)

We see, then, that Saul’s regeneration was not accomplished the moment he met Jesus in the road. He had to be baptized in order to wash away his sins and receive the Holy Spirit. Not only that, but it couldn’t wait — it was of the utmost urgency and necessity.

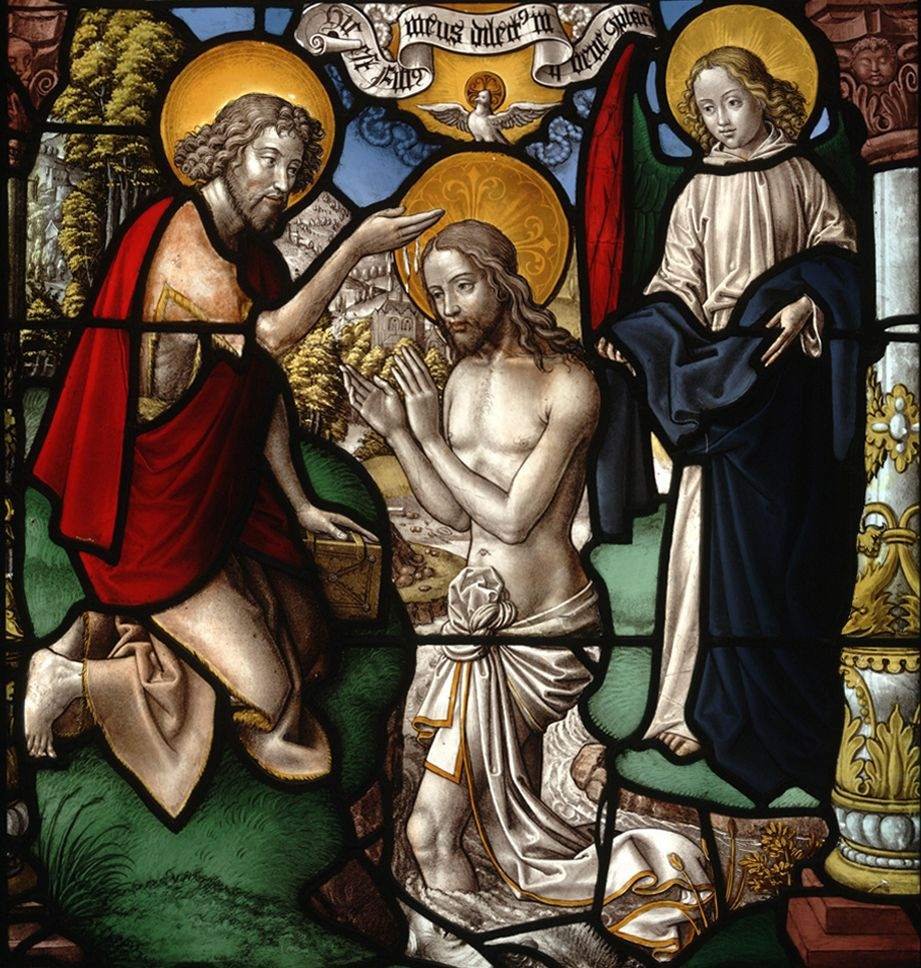

The Gentiles at the Home of Cornelius

The Baptism of Cornelius (1709), by Francesco Trevisani (Wikipedia).

While Peter was still saying this, the Holy Spirit fell on all who heard the word. And the believers from among the circumcised who came with Peter were amazed, because the gift of the Holy Spirit had been poured out even on the Gentiles. For they heard them speaking in tongues and extolling God. Then Peter declared, “Can any one forbid water for baptizing these people who have received the Holy Spirit just as we have?” And he commanded them to be baptized in the name of Jesus Christ. Then they asked him to remain for some days. (Acts 10:44–48)

Here these Gentiles do receive the Holy Spirit prior to their Baptism — hence the Jews’ amazement! They have been, indeed, regenerated apart from Baptism. But if Baptism were not essential, why is it the very first thing Peter thought of when he witnessed this miraculous manifestation? And is this situation the rule, or another exception? Do any other cases support its being an ordinary occurrence?

We don’t have to look very far, in fact, to find a counterexample:

While Apollos was at Corinth, Paul passed through the upper country and came to Ephesus. There he found some disciples. And he said to them, “Did you receive the Holy Spirit when you believed?” And they said, “No, we have never even heard that there is a Holy Spirit.” And he said, “Into what then were you baptized?” They said, “Into John’s baptism.” And Paul said, “John baptized with the baptism of repentance, telling the people to believe in the one who was to come after him, that is, Jesus.” On hearing this, they were baptized in the name of the Lord Jesus. And when Paul had laid his hands upon them, the Holy Spirit came on them; and they spoke with tongues and prophesied. There were about twelve of them in all. (Acts 19:1–7)

Here we likewise see Gentile converts, who had not yet been baptized with Jesus’s Baptism, but only with “John’s Baptism.” They had “believed” and were apparently “disciples” of Christ — and yet had they really heard the full Gospel of Christ, if they had not even heard there was a Holy Spirit? We observe several things:

- These believers had not yet received the Holy Spirit — and the first thing Paul asked them was “Into what, then, were you baptized?” Paul’s implication is clear: if they had been baptized properly into the Baptism of Christ, they should have received the Holy Spirit.

- If they had been baptized into Christ, they also should have heard of the Holy Spirit — suggesting that despite St. Luke’s reference to being “baptized in the name of Jesus,” the Apostles did in fact baptize “in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit” (Matthew 28:19), the traditional Trinitarian formula which the Church has always observed. [The Oneness Pentecostals, for example, seize on this verse and several others in the Acts of the Apostles to insist that they should baptize only “in the name of Jesus,” contrary to orthodox Christian practice.]

- These disciples received the Holy Spirit only after their Baptism, not before, when they profess to have “believed” (even if their understanding appears to have been incomplete). Clearly, then, mere “faith” or belief was not sufficient for their regeneration. This invalidates the above example from Acts 10.

The conversion of the Gentiles at the home of Cornelius, then, appears to have been an exceptional case, a demonstration of the power of God to save and regenerate even Gentiles, specifically to convince Peter of their inclusion into Christ. The manifestation coincided with Peter’s vision of Acts 10:9–16, a similarly direct intervention and revelation, and clearly itself an exception from the mode in which believers were generally saved. Once these Gentiles had believed, Peter urged them to Baptism as the essential next step, for their incorporation into the Body of Christ, the Church.

Believers Baptized but not Regenerated?

Almost as a counterpart to the previous example, here’s one more, presenting an opposite problem: these believers had been baptized, but had apparently not received the Holy Spirit.

Now those who were scattered went about preaching the word. Philip went down to a city of Samaria, and proclaimed to them the Christ. And the multitudes with one accord gave heed to what was said by Philip, when they heard him and saw the signs which he did. For unclean spirits came out of many who were possessed, crying with a loud voice; and many who were paralyzed or lame were healed. (Acts 8:4–7)

Now when the apostles at Jerusalem heard that Samaria had received the word of God, they sent to them Peter and John, who came down and prayed for them that they might receive the Holy Spirit; for it had not yet fallen on any of them, but they had only been baptized in the name of the Lord Jesus. Then they laid their hands on them and they received the Holy Spirit. (Acts 8:14–17)

Now, this does appear to present a complication. Had these people really been baptized and not regenerated? This poses an equal problem to both the Baptist and Catholic views. To the Catholic, it would seem that Baptism had not regenerated them; to the Baptist, it would appear that believing in Christ had not regenerated them!

Again, we observe first of all that the expectation was that these believers would have received the Holy Spirit at their Baptism; because they had not, the Apostles Peter and John had to make a special trip. But there is even more going on here than first appears. Clearly, when Philip (this is Philip the Deacon, not Philip the Apostle) brought the Gospel to Samaria, the Holy Spirit worked through him miraculously, exorcising unclean spirits, healing the lame and paralyzed. That the Holy Spirit came upon these people with such wondrous manifestation as they believed and were baptized does indicate, in fact, that they were regenerated, born again in Christ — they did receive the Holy Spirit. So why did Luke say they had not?

In the interpretation of the Catholic Church, what we are witnessing here is an early example of the Sacrament of Confirmation. Because this was yet early in the development of the Church and of Christian doctrine, St. Luke didn’t know quite how to describe what was happening. But yes, the Samaritans had been baptized in Christ and had been regenerated, and had received the Holy Spirit in some measure. But they had not received the Holy Spirit in His fullness, in the full anointing of Pentecost. Because this was one of the first times a missionary who was not an Apostle had preached to people unto conversion, it was probably just as much a surprise to Philip and to the Apostles as it is to us, that these new believers did not receive the fullness of the Holy Spirit. As the teaching of the Church developed, it was understood that the Sacrament of Confirmation could only be conferred by a bishop (a successor of the Apostles) or by a priest to whom the bishop specifically delegated it. In the previous example from Acts 19, when Paul “laid hands” on the newly-baptized believers, this too is understood as the completion of their baptismal grace in the Sacrament of Confirmation.

Conclusion

In conclusion to what I realize is a really long post — but one which I hope has been revealing and helpful — I do not believe that these four examples, unusual and early cases of conversion and regeneration, support the Baptist position, that Baptism is purely symbolic and unnecessary for salvation. Even these examples, when examined closely, indicate strongly that Baptism was necessary and efficacious in accomplishing the grace of Christ, through the working of the Holy Spirit. Next time, I will explore in depth some of the many other references to Baptism in Scripture, which likewise support a sacramental understanding.