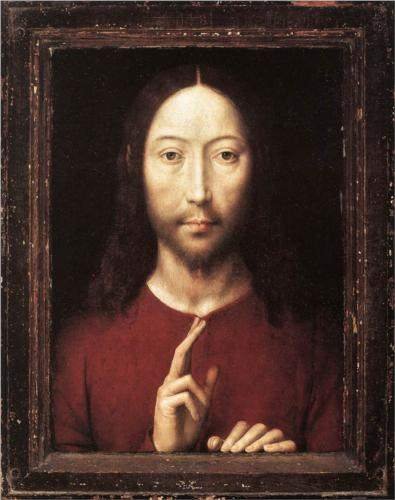

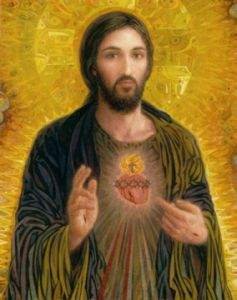

Sacred Heart of Jesus, by Smith Catholic Art (prints available).

I have other things to do today [insert other usual disclaimers which I then go on to ignore], but my dear friend Laura of Catholic Cravings and my new friend Ryan of the Back of the World are inaugurating their splendid new effort, O Most Sacred Heart of Jesus, and tomorrow, by my reckoning, being the First Friday of September, I wanted to be a part of their first First Friday Linkup, in which we all blog about the same thing, our Lord’s most Sacred Heart. Since Laura lives on the other side of the world (I’m not sure which side is the rear end?), and we are going by her clock, it will be First Friday by the time I finish writing this post.

The suggested topic for this month is “How did [I] first learn about the Sacred Heart?” In order to be brief, for the sake of their readers as well as my other-things-to-do, I will do my best to constrain myself to that. This will be a little of a rambling journey, I’m afraid, and as a further word of warning, I almost always have more to say than I mean to, or than anybody wants to read!

Growing up in evangelical circles, having little knowledge of the Catholic Church but having occasional, cultural brushes with it, I had heard of this “Sacred Heart” thing. Churches were named after it, and I had encountered the artwork of Jesus revealing His heart, especially in an area with a growing Hispanic population — but I never had any idea what any of that meant. And then one day — perhaps as one of the last important signposts to my Catholic journey, when I still had no idea I was on a Catholic journey, no intention at all of becoming Catholic — it gripped me.

It was the very first week of grad school, in my new apartment in a new place. I was feeling the stirrings of a new call to faith, and was wrapped up in searching for churches to visit, to finally find where I belonged. I did visit the Catholic Church during that time, but had found it offputting and dismissed it; I’ll tell that story before too long. Browsing around on the website of a Christian book and music seller, a new artist jumped out at me: Audrey Assad. I’m not even positive that I knew she was Catholic before I bought her CD. She was nerdy-cute, and a singer-songwriter, and I had a new friend named Audrey (who is Catholic), and that was probably enough to reel me in.

And in the very first track on the CD, it took me aback:

And for Love of You, I’m a sky on fire

And because of You, I come alive

And it’s Your Sacred Heart within me beating

Your voice within me singing out,

For Love of You,

O for Love of You.

I froze in what I was doing. I literally heard it in capital letters: Your Sacred Heart within me beating. That’s something Catholic, I thought. And I felt my own heart beating; my hand on my chest; the blood rushing to my head. Is Your Sacred Heart beating within me, Jesus?

I had never thought of the Heart of Jesus that way before. Sure, of course, Jesus had come to live in my heart. But was His Heart beating within me? — His love for all the world? Did I have the Heart of Jesus?

(If I hadn’t already known it, I quickly confirmed in the liner notes of the CD: the lyric printed as Your Sacred Heart. Audrey Assad is a Catholic convert, raised in a Protestant household and coming to the Church at age 19. And please, my brothers and sisters, pray with Audrey — who is of Syrian descent — and with Pope Francis, and with the whole Church, for peace in Syria and in the Middle East.)

It would still be another six months before I would be drawn back to the Catholic Church, nudged by the local Audrey. But that moment would always stay with me. On one of my thrifting adventures within the next year or so, I ran across a wonderful book on the theological and scriptural and mystical foundations of devotion to the Sacred Heart: Heart of the Redeemer by Timothy T. O’Donnell, through Ignatius Press — so I had no doubt that it would be good. Contrary to what some have asserted, devotion to the Heart of Jesus has a firm and deep grounding in Scripture itself, which, upon learning and studying it, captured my whole mind and heart, and brought me to fall in love with Jesus all over again, with His Heart — which, I pray, may ever beat within me.

I have so much more to share about my Lord and His Sacred Heart! Thank you, Laura and Ryan, for the opportunity!