(I shouldn’t write much today. I stand poised to wrap up a draft of the last chapter of the thesis. But I know it’s been a little while and I wanted to share a little bit lest you forget about me. I have a bit of previously written material I may share over the next week or so.)

One thing in particular I’ve been thinking about lately is how knowledgeable Protestants can tenably defend their doctrines; how anyone, reading the writings of the Church Fathers, can honestly contend that the tenets of the Reformation were anything but a sixteenth-century invention, a novel interpretation of Scripture unsupported by any authority other than the interpretation of the Reformers — but trumpeted as “the authority of Scripture.” I’ve got news for you: despite your constant assertions to the contrary, your interpretation of Scripture has no inherent authority; it has only the authority you yourself give it and others might or might not accord it. If it did have a universal and absolute authority — if your interpretation of Scripture could be equated with Scripture itself — then it could not but be universally recognized, and could not fail to settle every doctrinal dispute and end every schism. If Scripture could indeed speak for itself, with a clear and perspicuous voice, then it would indeed be the ultimate authority, for it is God Himself speaking.

But Scripture does not speak for itself; it does not edit itself; it does not translate itself; it does not interpret itself. Any reading of Scripture involves the apprehension and comprehension of the human mind; and any reading of Scripture in English involves reading what has already been apprehended and comprehended and reproduced by quite a few people before it came to you. As it stands, under the doctrine of sola scriptura, no matter how one formulates it, the authority of Scripture must always stand upon the authority of someone’s interpretation — be it your own, your pastor’s, your presbytery’s, your church’s, or the Reformers’. The question necessarily becomes not what authority Scripture has but what authority your interpretation has.

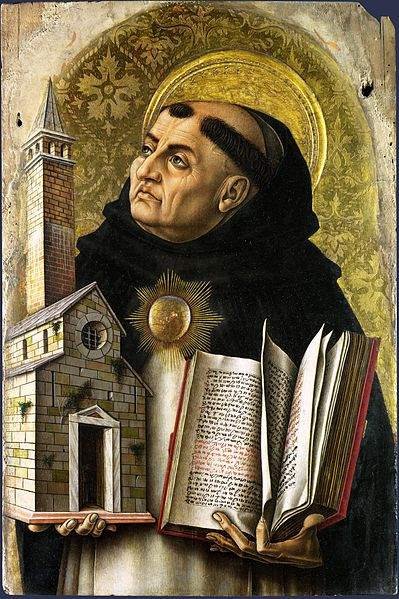

St. Thomas Aquinas (15th century), by Carlo Crivelli. (Wikimedia)

So it is also in the Catholic understanding also, of course: our understanding is built on an interpretation, also. We ask, too, what authority our interpretation has; and rather than looking to ourselves, or to any single man or group of men, we look to the amassed weight of the whole of the Christian tradition, to the interpretations of those who first received Scripture, who understood it in its time and context, and to the many pastors and teachers and exegetes and theologians who have taught on it, thought on it, commented on it, and carried it forward through time to us. This tradition has authority in itself, supported by the very pillars of history. But even beyond that, we look to the voice of the combined Church, to the agreement of the whole people of God, and to the consensus of her bishops, invested with the authority of the Apostles from Christ Himself: to the Church to whom He promised the Holy Spirit, Who would lead her into all truth (John 16:13), to the Magisterium, which speaks with His authority (Luke 10:16).

This screed is not what I set out to write today. Oops. But sola scriptura and the question of authority has certainly been at the forefront of my thought recently, and I expect to be writing a bit more on it in the near future.